Thanksgiving has always been a puzzle to me. As a German exchange student in 1993 in Virginia I remember it mostly for the empty campus. While people went home to overeat, the rest of us looked at closed restaurants and college food services. Later, when I was a grad student in New Jersey, the international students on campus staged our own improvised Thanksgiving, with our own cultural foods, mostly to stave off the sense of being left out of the celebration. As a foreigner, one is often left out of the traditions that most signify a culture. The only positive I have found in my years in the US is being introduced to pumpkin pie—and even that was an acquired taste.

Meanwhile, Thanksgiving is not an unusual feast, though American exceptionalism may perpetuate that thought. Most agricultural societies have some form of harvest festival—what especially distinguishes the US celebration is the clumsy attempt to turn a history of colonization, broken promises and treaties, landgrab and genocide into a false harmonization of history.

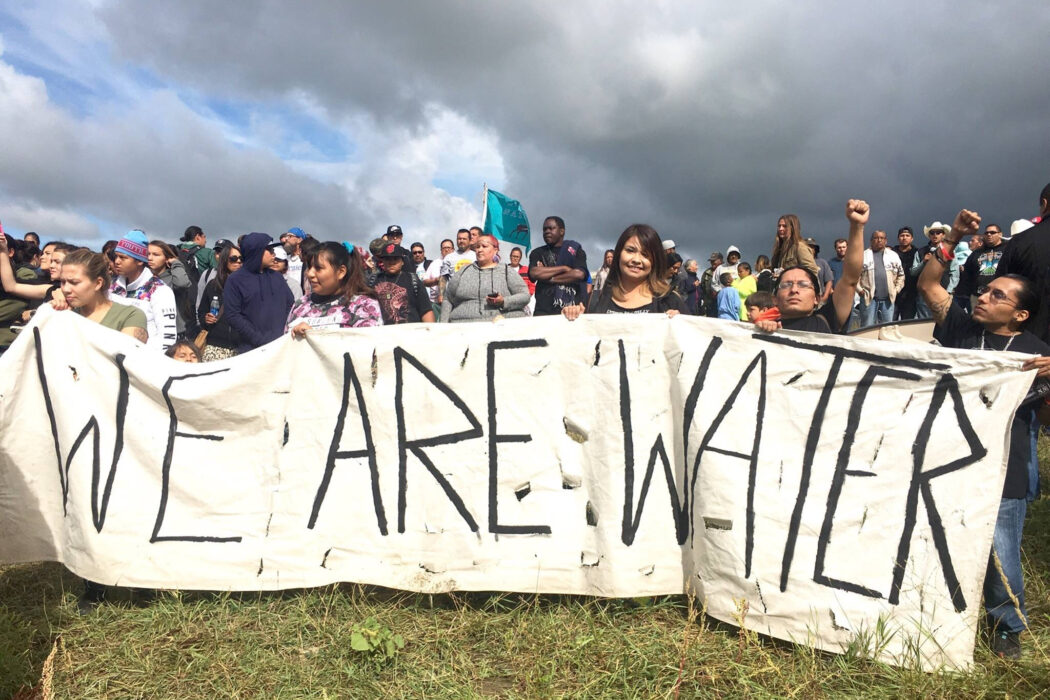

For many Native Americans, unsurprisingly, the holiday has been a day of mourning, of gift economies overrun by profit-focused capitalist systems. This has become glaringly visible in the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline this year.

There may be many reasons to give thanks but the agricultural and earth connections of this holiday seem to have become as thoroughly de-naturalized as many of the products shilled on Black Friday, a day energized by the false promises of goods fueled by petroleum consumption. Some have declared Black Friday “Buy Nothing Day,” or added a Green Saturday. Just focusing again on the fruits of the earth, and giving thanks for the water that sustains us all and its endangered state is a huge improvement.

In Oceti Sakowin camp on Standing Rock reservation, we learned this week about the elemental nature of water and its centrality to life. “Mni wiconi,” Lakota for “water is life,” is the battle cry of this camp and this movement—and it will not go silent no matter what happens with this particular pipeline. The movement is already far bigger and visitors are encouraged to take the fight for the preservation of water to the places where they hail from.

The vision is compelling, it brings to the fore a spirituality of respect for the cycles of the four elements, unites the four peoples (black, red, white and yellow), and pulls in people from all four directions. It has become the heart of a pulsing new movement. I spoke with many in camp who said that they had been waiting for this kind of movement, felt a pull, a draw, a need to be there. Many of us have already been working on related issues for decades, but it is perhaps this kind of integrated, open, deeply spiritual and religious narrative of the sacred that has been missing.

The vision of the movement gathered at Standing Rock is anything but secular, it is deeply religious and spiritual, but also defiant of those two overused categories. There is something about this vision that is deeply uninterested on whether it confirms any of the trends toward or away from religion that some readers of Pew surveys have been anxiously eyeing.

At the center of the camp is the Sacred Fire. No images are to be taken of it, partly, as one of the elders explained, so that we would have to remember what happens around the fire in our hearts. And that it has done. Words spoken at that fire have already made a deep way into my heart.

The Sacred Fire is one where we bring the best in us, no curses, no dark thoughts, a place that is meant to discipline us into kindness, respect, and love. There is something almost monastic to the call that the encampment is neither a festival nor a fun camp. Alcohol and drugs and the ravages they have brought, especially to Native peoples, are banned. Rather, the camp is a ceremony, a call to bring forth the best in each of us, and to act accordingly.

We are encouraged to live our entire lives as ceremony by one of the elders, in a mode that reminds me of the sacramental life—all of life and all of creation as a sacrament. And that means moderation in our participation of the dynamics that enable the Black Snake of Hopi prophecy. From what I could gather the Black Snake is both the pipeline, as well as all efforts to harness amounts of energy and consumption that are destructive to sustainable lifeways. As I look outside the window of my airport hotel near JFK, the band of the clogged freeways through Queens are the Black Snake, as are my laptop and my tablet, the energy that powers them. It is something that we are all addicted to together. The elders in camp and the movement speak clearly about the common addiction that fuels the push for the pipeline. None of us is outside of the economy of the Black Snake. But many see the need to escape it, and as quickly as we can.

The resistance to the Black Snake is not simply a story of settlers versus natives. When I did research on oil in Alaska, there were some Natives who were profiting from oil and gas leases, and others, specifically the Gwich’in, who had chosen to remain outside of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and not sell their future for a mess of oil pottage. I spoke to a water protector and he indicated that the line between those for and against the pipeline runs between family and tribal members as well as among indigenous and settlers. And whether we are for and against, we all are involved in pushing the demand in the one or other way. We may know we need to stop, but we do not know how.

Thanksgiving in the US is an orgy of food consumption followed by the crazed shopping of Black Friday. One could say both of these days have become a celebration of the system of overconsumption of resources that has all of us of tightly in its grip, no matter which side of the Standing Rock fence we stand on.

It might be a good thing that the Stingrays are blocking the signals in most of the camp. They might be doing us a favor, keeping us from having our necks bent out of shape from staring at mobile screens. Instead, we are talking to other people, making connections, building networks, hearing stories, affirming and strengthening each other.

The Black Snake poisons us all, paralyzes us with its eyes while we continue destroying our common livelihood.

A Site of Pilgrimage Already

While a poster onsite says “no pilgrims,” it refers only to the Puritan settlers of history. In fact, the Oceti Sakowin camp receives many pilgrims each day. They come from indigenous nations around the world, and there are many instances of sharing of food and resources. When I was there for the second time, for a few days this week, donations of food were rolling in heavily, firewood was delivered, and for the 9am orientation session inducting novices in the basics of the camp’s principles (indigenous leadership, no drugs, no violence, no unauthorized actions, no property damage) the group of newcomers was so large that for the first time since the establishment of the camp orientation had to be split in two.

It is heartening to see many young indigenous women in particular lead and speak. They are quick to tell the gathered crowds that they are are college-graduated and able to use tech-savvy information strategies through outlets such as Indigenous Environmental Network and many others. They are gloriously hybrid leaders—the “digital natives” nobody was thinking of when they coined that term—combining the best of subversive education and information technology, blending indigenous and post-industrialized ways of being to combat the common lack of the greater thanksgiving to the earth.

There is a site in camp called “Facebook hill” because it is the only location that eludes the government stingrays and planes blocking the communication signals of those gathered. While the governmental forces’ intent may have been the repression of communication in and about the camp to the outside, it has another unintended effect. Campers talk to each other, look into one another’s faces, make connections, share stories, worries, and coping strategies. We all know these are difficult and dark times, and we need one another if the earth is to bring forth new harvests.