Montclair High School recently found itself embroiled in a controversy of its own making when it decided to honor the late Rabbi Meir Kahane as part of its Jewish Heritage Month communication, a choice baffling to Jews and Gentiles alike.

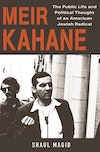

Kahane’s name is notorious in most Jewish circles, where his status as persona non grata has left many to shrug off his influence as a relic of a shameful past. But the reality is that Kahane’s legacy on Jewish communities has been profound, and not just in Israel. As Jewish Studies scholar Shaul Magid argues in his new book, Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical, Kahane’s ideological legacy has had a lasting impact on Jewish self-conceptions, which is perhaps most salient in the diaspora.

Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical

Shaul Magid

Princeton U. Press

October, 2021

RD recently spoke with Shaul Magid about Kahane’s role in shaping post-Holocaust Jewishness; the effect he had on discourses around antisemitism and Jewish “continuity” (or survivalism, as Kahane called it); and what the future of Kahanist ideas might look like both inside and outside of Israel.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What got you started on this book and how did you first encounter Meir Kahane?

I lived in Brooklyn in the late 70s and he was ubiquitous. He had already been living in Israel, but spending a lot of time in the United States. So he was somebody that was very often around, though I never took the opportunity to hear him speak. There was still some semblance of the JDL [Jewish Defense League], and I talk in the introduction that I had a roommate who was in the JDL, an unassuming and fragile kind of guy, but I got a little sense of what the JDL was about in the late 1970s.

So that’s how I encountered him. But then I moved to Israel, and in the 80s he was around and he would give talks, but he never really caught my attention. I never thought there was something that interesting about him.

I wrote a book in 2015 called American Post-Judaism and I wanted to do a section with an analysis about different people’s response to the Holocaust who aren’t people you normally hear, so I included about ten pages on his response to the Holocaust. I had a graduate student at that time who’d read it and then decided he wanted to do a master’s thesis on Kahane. He was interested in questions of history and memory. So we set up a weekly meeting where we just started going through all of his writing from the early 1960s onward.

It was there that I realized it wasn’t just the ramblings of a madman, so to speak, but a coherent worldview that was original. That’s where I decided I wanted to do something on Kahane, though I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. In a way, then, my Kahane book is a sequel of sorts to American Post-Judaism, which was really looking at Judaism and post-ethnicity in the 21st Century.

How did Kahane understand Jewish ethnicity? You discuss in the book how he often held up converted Jews of color as important community members as a way of ducking allegations of racism, but how did Kahane actually define who a Jew was?

He had a pretty conventional understanding of who a Jew is. A Jew would be a person who inhabited a Jewish womb, born of a Jewish woman. That’s pretty much it for him. And that was not what interested him as much as what it meant to be a Jew. So one can be physically Jewish, but not actually a Jew. And that’s what he was trying to construct, a new way of being a Jew that cultivated pride in being Jewish as opposed to the image of the emasculated survivor quietly living a Jewish life without a mission other than hiding from antisemites.

Kahane’s whole project was pushing back against the post-war Jewish quiescence that was saying let’s keep our heads low and not make trouble. He used to tell a joke about two Jews in front of a firing squad. Both Jews are blindfolded and one calls out to the guards and says his blindfold is too tight, and the other one says “don’t make trouble.” Kahane felt like this was the quintessence of what the diaspora had done to the Jew. It has weakened them.

How did Kahane’s idea of survivalism—or the imperative to ensure the continuity of the Jewish people—affect the larger Jewish community?

Obviously Jewish survivalism is largely a Zionist trope, or it’s become one. So what Kahane wanted to do was take the Zionist survivalist model and transport it to the American diaspora. Just like Zionism is about muscularity and fighting back and a certain type of machismo and chauvinism, he asked why the diaspora can’t do that as well. People think about Kahane and they immediately think about Zionism and Israel. But earlier in his career, it wasn’t that he wasn’t a Zionist, but he wanted to save the American dream for the Jew. The JDL was a diasporic project.

But he goes to Israel in 1971, and by 1972 he said that the JDL should be about mass aliyah; we have to get as many Jews to move to Israel as possible. And his colleague, Bertram Zweibon, said no, that the JDL was about protecting Jews in America. So I think there was a breach of Kahane’s idea at some point. But his goal was to bring Zionist muscularity into the diaspora. In addition he tried to convince Knesset members to support his mass aliyah project and none seemed very interested. For them, it seemed that supporting Israel in America was the job of American Jews.

This gets to the line you close the book with, which was that Kahane did actually hate Arabs, but not quite as much as he hated other Jews. What did he see as broken inside Jewishness? And, maybe it gets to a deeper question: what did he think Jewishness was? He both was against the kind of “normalizing” process of Zionism, but he also seemed to think that diasporic Jews needed to be redeemed. So what was this core of Jewishness he was after?

Kahane wrote a book called Listen World, Listen Jew, which was really a response to Vanessa Redgrave’s 1978 Academy Award speech where she mentions the JDL, calling them “Zionist hooligans” because they lobbied in Los Angeles to try to prevent her from winning an Academy Award for a movie that she helped produce about the Palestinians. It’s a fascinating story.

In that book, he offers a completely revised history of the Jewish people from the perspective of Bar Kokba, military leaders, that ends with the Irgun and the Stern Gang. That is the “true” trajectory of Jewishness for Kahane. It’s about militancy, it’s about power, it’s about conquest. It’s not about the martyr Rabbi Akiva. And ultimately it’s about the use of violence to protect Jewish bodies; everything else for him is kind of about how the diasporic experience has deluded the Jews such that they’re no longer aware of their true nature.

So in a sense what Kahane was saying, the muscular Jew of Max Nordau and early Zionism, that’s not a new creation. That’s basically reviving an old, authentic model of Jewishness. He thought that Zionism failed in its revision of Jewish history in only limiting it to the designs of the project of the Land of Israel, instead of bringing that revisionist history to the diasporic Jewish experience as well. Kahane wanted to revolutionize the figure of the Jew, for Jews and for the world.

What role did revenge play in Kahane’s thinking? Did it have a mystical component?

I don’t know if it was mystical, but revenge is very, very important for him, especially in the 1980s. His books 40 Years and Thorn in Our Side, both written mostly in Ramle prison, become a kind of theology of nekama (revenge), though I don’t think it’s revenge in any kind of mystical sense. It’s more that revenge itself cultivates a sense of power and identity. 40 Years is essentially built on his reading of the prophet Ezekiel, which as readers of the prophets know, is quite angry and vengeful.

I have another essay I wrote that talks about Kahane’s ethics of violence. Violence for him wasn’t only a deterrent, it was an act of self-formation, especially in America. This is very much in line with the Black Panthers, Black nationalism, and Malcom X. The idea of violence gives the Black person pride in being Black. And he felt that way about Jews too, so I think, for him, revenge wasn’t only a theological category, it was a sociological category as well. It gave people a sense of power.

You talk both about Black nationalism and Afro-pessimism; what influence did ideas like these have on Kahane?

Afro-pessimism didn’t exist then and has only existed for the past 15 years, so I’m sort of imprinting those ideas here. He was very moved by Black nationalism and was perfectly happy calling the JDL “Jewish Panthers.” He respected Sonny Carson (a local Black militant in New York) and Stokely Carmichael along with Malcolm X. He also thought they were antisemites and he fought Black antisemitism, which was the reason for him starting the Jewish Defense League during the 1968 New York City school strike (due to the antisemitism directed at union president Albert Shanker). So Black antisemitism does play a role.

He had this kind of twisted relationship with Black nationalists. On the one hand, he thought that Black nationalists were antisemites. But on the other hand, he really respected them and he modeled himself after them, to some degree, because they were creating a notion of pride and identity. So he countered “Black is Beautiful” with “Jewish is Beautiful” and he was, interestingly, unafraid to openly do that.

When Malcolm X was coming out against Martin Luther King Jr. and saying that integration was really the death knell of Black people, such as in the famous “coffee and cream” speech in 1965 where Malcolm talks about how when you put milk in coffee it gets weak and puts you to sleep, Kahane had a similar view; he was an anti-integrationist. He wrote a book on intermarriage, Why be Jewish?, in 1974. Who was writing about intermarriage in 1974? It wasn’t at the center of the Jewish conversation the way it is now. Kahane knew that was coming down the road.

So in a certain sense he saw that the Jews could survive in America if they created for themselves, not an enclave like you see with the [Hasidic] Satmar [community], but a sense of pride where Jews would marry and hang around with other Jews and act exclusively for the sake of Jews and Jewishness. And, if necessary, make other people afraid of them, frankly.

How did Kahane understand antisemitism and how has his understanding of antisemitism influenced, not just the Jewish right, but all of the Jewish community’s understanding of antisemitism?

His view of antisemitism wasn’t uncommon in his time in the Orthodox world in which he lived, but he was able to articulate it in a very particular way. For him, antisemitism was an unsolvable problem. It was endemic to the non-Jew. It was almost metaphysically written into creation itself (“Esau hates Jacob”)—he took that very seriously. So for him, the problem wasn’t eradicating antisemitism, that was impossible.

The problem was managing it; meaning you had to create enough of a deterrent that, ok, so the non-Jew is going to hate the Jew and there’s nothing you can do about that, but they aren’t going to act on it. And if they act on it they’re going to pay for it. So Kahane felt the Jew had to be more like the gentile, which he believed was actually being more like an authentic Jew. As he liked to say, Moses killed the Egyptian taskmaster in the Book of Exodus, he didn’t negotiate with him.

Tacitly, it seems like a lot of the conversation about antisemitism today is acknowledging Kahane’s basic approach—not his solution but his approach—but not being willing to fully acknowledge it. In other words, these people writing these popular books about antisemitism, they identify this or that incident of antisemitism—sort of like “the greatest hits of antisemitism.” But there’s never any real theorizing about why it happens or what it means. It’s always in the historical circumstantial register.

And yet, I think underlying it is this ontological claim that they never want to actually make. Which is that gentiles are always going to be antisemitic, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Because if you say that then there’s no solution to it. Kahane openly said there was no solution to it. He wasn’t alone, but he popularized the idea.

Kahane was willing to declare that there’s no solution to it. That’s the way the world is. So we have to basically create a deterrence that will prevent Jews from being harmed by it. And I think there’s a real sleight-of-hand going on in the contemporary discussion of antisemitism that’s not willing to admit Kahane’s view (which was not only his view, but the view of others as well). Part of the question I have on the writings about contemporary antisemitism is what’s really going on? What’s this actually all about? Many have written about it; for example, Hannah Arendt and contemporary Jewish historian David Engel. But who’s really reading them outside academia? The popular discussion about antisemitism today is sorely under-theorized.

I just read an excellent new book, still in manuscript, by a young scholar on middle-brow Jewish writing in the mid 20th Century. One of the things she shows is that from 1945 to the early 1960s there were dozens of books written by rabbis and Jewish scholars about basic Judaism, such as Milton Steinberg’s Basic Judaism or Irving Howe’s World of My Fathers. There was a famous Life magazine cover story about Jews, and all kinds of stuff that would explain Judaism to Christians and act as a crash course in Jewish literacy.

But today, everybody’s just writing about antisemitism; few writing popular books about Judaism anymore. So somehow antisemitism has overtaken the discussion about Judaism and that’s why some of these books are bestsellers, because Jews are running to read books about how people seem to hate Jews [or love dead ones]. Because in some way this has become a source of Jewish identity. Why would you want to read a book about people who hate you unless it fills some kind of gap or feeling in why you should be a Jew? One of those books ends by saying the response to antisemitism is to “be more Jewish.” As if that’s the reason to be more Jewish. Something is very wrong here.