Alabama is the latest state to reconsider its stance on yoga, as reported by The New York Times earlier this week (an article for which I was interviewed). The 1993 Alabama State Department of Education Administrative Code prohibits public school personnel from using “any techniques that involve the induction of hypnotic states, guided imagery, meditation or yoga,” and defines yoga as “a Hindu philosophy and method of religious training in which eastern meditation and contemplation are joined with physical exercises, allegedly to facilitate the development of body-mind-spirit.”

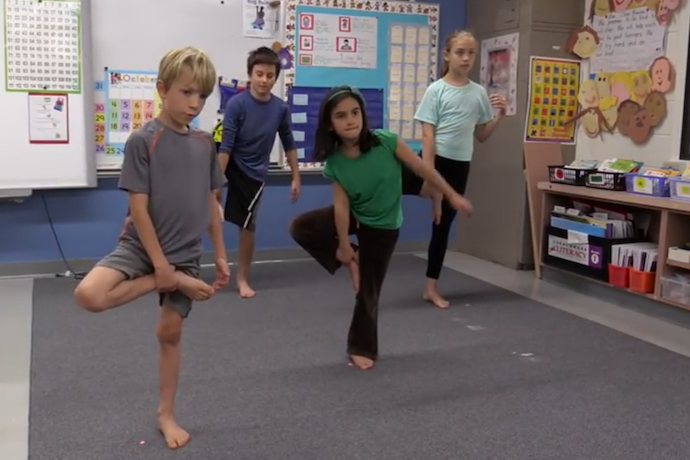

The proposed law, passed by the Alabama House of Representatives on Tuesday, would allow K-12 public schools to offer yoga as an “elective,” as long as “students shall have the option to opt out.” Moreover, “instruction in yoga shall be limited exclusively to poses, exercises, and stretching techniques,” with “exclusively English descriptive names,” while “chanting, mantras, mudras, use of mandalas, and namaste greetings shall be expressly prohibited.”

For Americans who associate yoga with Lululemon, YMCA fitness classes, and kale smoothies, Alabama’s discussion may seem utterly baffling. Part of the confusion is that “yoga” has meant many things over time and across space. The 2016 Yoga in America Study reports that 36.7 million Americans—15 percent of all adults—now practice yoga. A quarter of practitioners cite “spiritual development” as a motive, whereas 9 percent of non-practitioners avoid yoga because “the ‘spirituality’ aspect of the practice bothers me.” Alabama seems to be seeking to capture the perceived physical and mental health benefits of yoga, while avoiding its spiritual connotations.

Speaking out in opposition to the bill, according to AL.com, is evangelical activist Dr. Joe Godfrey, who “told committee members that yoga is a religious practice.” Although it would be simplistic to equate yoga with Hindu religion, neither is the association baseless. Setting aside the legal question, Dr. Godfrey does, in fact, have support for his statement about yoga’s religious content from some unexpected places.

One of the most significant influencers of modern American yoga culture is the Indian Hindu Shri Krishna Pattabhi Jois (1915-2009), reputed developer of Ashtanga Yoga (who has been credibly accused of sexually assaulting trainees). According to Jois, “the spiritual aspect, which is beyond the physical, is the purpose of yoga.” Specifically, “the reason we do yoga is to become one with God [Brahman].” Jois envisioned the Sun Salutations (Sūrya Namaskāra) that characteristically start Ashtanga practice as a physical act of “prayer to the sun god,” Surya—whether or not this pose sequence is called by its English or Sanskrit name, and regardless of whether practitioners intend their actions as exercise or worship. By Jois’s design, “for anyone who practices yoga correctly, the love of God will develop . . . whether they want it or not.”

Lobbyists supporting the change in Alabama law include Rajan Zed, President of the Universal Society of Hinduism, who urged lawmakers “to wake up to the needs of Alabama pupils.” Zed has been outspoken in a number of yoga controversies in recent years. Notably, he opposed a 2014 tax on D.C. yoga studios as a “religious infringement”—arguing that yoga is “one of the six systems of orthodox Hindu philosophy” and “a mental and physical discipline by means of which the human-soul (jivatman) united with the universal-soul (paramatman).”

If Godfrey, Jois, Zed, and Alabama legislators are correct in identifying yoga as a religious practice, then restricting yoga instruction in public schools aligns with legal precedent. The Supreme Court ruled in Engel v. Vitale (1962) that schools cannot provide instruction in religious practices such as school prayer—even if students are allowed to “opt out” by remaining silent or leaving the room.

A federal appellate court held in Malnak v. Yogi (1979) that an “elective” course in Transcendental Meditation constitutes an “establishment of religion,” in violation of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Thus, although the Alabama House has carefully restricted yoga classes to “electives” from which students may “opt out,” such caveats could be legally meaningless.

Public school yoga programs have generated legal controversies before. In 2013, a California judge determined that “yoga is religious,” yet allowed a school program (based on Jois’s Ashtanga yoga and funded by the K. P. Jois USA Foundation), reasoning that it is possible to strip yoga’s religious “trappings” by relabeling poses such as “lotus” as “criss-cross applesauce.” In 2016, however, the Pennsylvania Board of Education ruled that a yoga-based charter school is legally impermissible because the curriculum retained language used in “religious instruction.”

These rulings, like Alabama’s recent legal wordsmithing, reflect a Protestant-derived, Word-centered understanding of “religion” as consisting primarily of verbal communication of beliefs, rather than performance of bodily practices. Legislators are optimistic that they can have their yoga without establishing religion, as long as they remove Sanskrit terms and chants.

By contrast, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) interprets Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as defining religion “very broadly” to “include ‘all aspects of religious observance and practice as well as belief.’” In 2008, the EEOC singled out mandatory “meditation, yoga” as “reverse religious discrimination,” even if employers have the secular goals of improving “motivation, cooperation or productivity.” By this reasoning, schoolteachers cannot be obligated to teach yoga or meditation if they raise religious objections.

But the strategy of relabeling yoga to make it sound more secular has alleviated previous bouts of concern. When Tara Guber’s Yoga Ed. program generated protests from a Colorado school board in 2002, she modified the language, replacing “samādhi” with “oneness,” “meditation” with “time in,” and “prāṇāyāma” with “bunny breathing.” Once the controversy died down, she told an interviewer from Hinduism Today that semantic changes are superficial, since yoga practice itself will “go within, shift consciousness and alter beliefs.” Thus, getting yoga into schools, albeit without Sanskrit terminology, amounted to a “Vedic Victory.”

Even if the Alabama Senate refuses to pass the House bill, the state’s school children will not be deprived of exercise or even stretching. The required and elective classes included in Alabama’s current physical education (PE) guidelines list, among other activities, “stretching”—just as long as it’s not “called Yoga.”