There’s a lot happening in Hopkinsville, Kentucky the weekend of August 18. The town is hosting cast members from The Walking Dead and JEM at a local Comic Con; the director of the Vatican Observatory is giving a speech on “Faith and Science” at a local Catholic church; a local distillery is putting on a “Kentucky Bourbon Mashoree.” And, of course, at 1:24 PM on Monday, August 21, this sleepy Southern town of thirty-three thousand will become the “point of greatest eclipse,” the place where the sun will vanish completely behind the moon for two minutes and forty-one seconds, longer than anywhere else on earth.

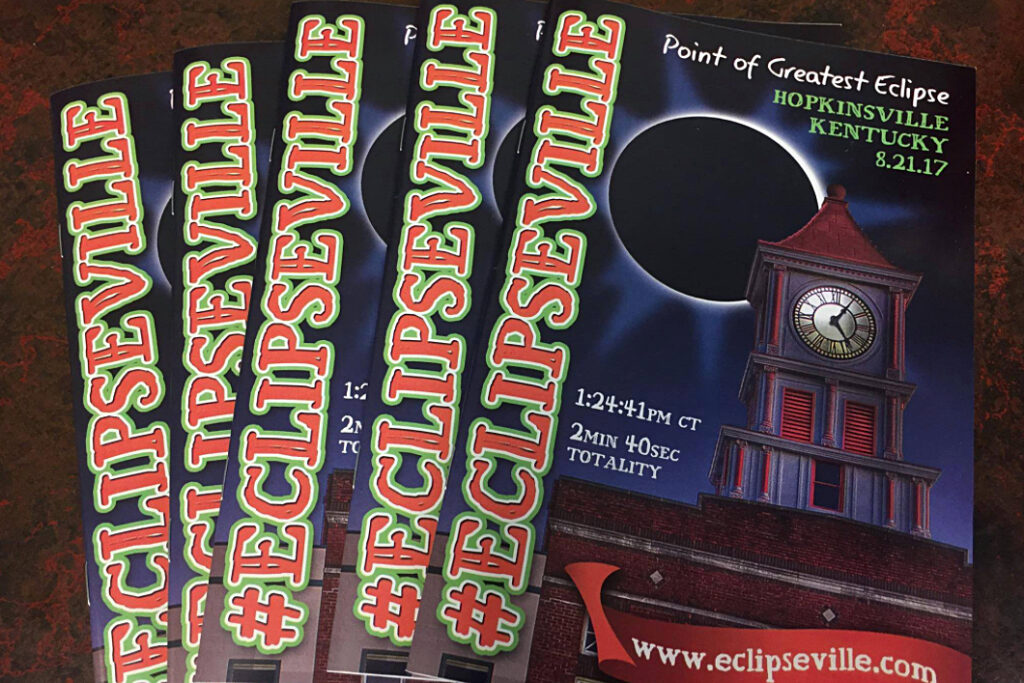

The people of Hopkinsville are for the most part happily bracing for the event. Hopkinsville leaders have dubbed their town “Eclipseville” and are expecting tens of thousands of visitors to crowd their hotels and restaurants. They say Hopkinsville is big enough “to make your solar eclipse experience memorable” but also “small enough to make sure you feel at home.” In addition to encouraging visitors to sample the local hops at the Bourbon Mashoree and drop $90 to camp in the local park, Hopkinsville is peddling Eclipseville blankets, caps, and tumblers. They’re selling the radically weird experience of a full eclipse leavened with small-town Southern hospitality.

The people of Hopkinsville are for the most part happily bracing for the event. Hopkinsville leaders have dubbed their town “Eclipseville” and are expecting tens of thousands of visitors to crowd their hotels and restaurants. They say Hopkinsville is big enough “to make your solar eclipse experience memorable” but also “small enough to make sure you feel at home.” In addition to encouraging visitors to sample the local hops at the Bourbon Mashoree and drop $90 to camp in the local park, Hopkinsville is peddling Eclipseville blankets, caps, and tumblers. They’re selling the radically weird experience of a full eclipse leavened with small-town Southern hospitality.

Selling is the right word. What’s happening in Hopkinsville this weekend is the resoundingly human process of grappling with the mysterious, the frightening, and the strange: we wrap it in what we know (perhaps in a $30 Eclipseville-branded fleece blanket). As the town tries to domesticate the eclipse and convert its weirdness into a boon, Hopkinsville’s citizens are revealing what’s important to them, whether they be civic-minded citizens of an economically struggling Southern town or science-minded emissaries from the Vatican. This is something we all do, but Hopkinsville has an advantage: in addition to being the center of the nation’s eclipse craze, the town is also the site of one of America’s most documented encounters with creatures from a UFO. That story reveals that Hopkinsville has a long history of using heavenly oddities to sate very earthly desires.

Lucas Reilly writes that over the ninety minutes or so that the eclipse proceeds relentlessly from first intersection between the sun and moon toward what’s called totality, birds will stop singing. Chickens will, eerily, stand on one leg. The wind will change direction and odd shadows will flicker across beaches. Annie Dillard describes how colors become wrong and landscapes devastated. It is not terribly surprising that ancient Americans offered human sacrifice to save the sun as the sky darkened, nor that medieval Catholics flocked to confession when an eclipse approached—and nor even that, as Reilly describes, a small band of eclipse-chasers even today spend their lives pursuing the weird rush of standing beneath a covered sun.

An eclipse quite literally upends one of the basic premises upon which human life functions: that the sun should rise in the morning and set at night. It reveals for a few moments that the regularity our rationality imposes on the universe must always bear exception. While Hopkinsville’s boosters promise that the town has enough bed-and-breakfasts and cell phone towers to transform the eclipse into a comfortable tourist experience, there is a fundamental strangeness to the whole affair that no amount of merchandizing can fully defang.

That it’s hard to reduce the weirdness of things like the eclipse hasn’t stopped Hopkinsville from trying. More than a half-century ago, on Monday, August 22, 1955, news media around the country reported that the previous night, several Hopkinsville residents reported that aliens had besieged their farmhouse.

At seven o’clock in the evening on August 21st, a young man named Billy Ray Taylor sprinted to the back door of a farmhouse a few miles north of Hopkinsville in the small township of Kelly. He had left to fetch water from the well a few minutes before, and as he hauled up the bucket he glanced to the southwest and saw a gigantic silvery flying saucer cruising silently toward the house. Billy Ray watched until the saucer dropped out of sight, plunging into a gully at the edge of the farmland.

Back in the farmhouse Billy Ray’s friends and family scoffed at his story, but their fun ceased when, a half hour later, the dog in the backyard began to bark violently and fled under the house. Billy Ray and the son of the farmhouse’s owner, Lucky Sutton, went to the door and saw a strange glow slowly drifting toward them.

The small figure approaching in the light had a round head, large wideset yellow eyes, and arms that reached almost to the ground. It was about three and a half feet tall, and it gave off a cold, silvery luminescent glow. Its taloned hands reached toward the men as it glided toward the house. Billy Ray and Lucky recoiled, seized rifles, and fired. The creature, they said, “did a flip” backward and retreated into the dark. So did the men, into the farmhouse.

Over the next several hours, yellow eyes appeared at windows. Talons scraped the farmhouse shingles. The witnesses claimed the creatures could float to and from the branches of the farmhouse’s trees. At one point, Billy Ray ventured onto the porch and a spindly hand reached down from the roof and grasped his hair. Alene Sutton screamed and dragged the young man back inside. The men fired shots at the creatures at least four times but never seemed to do any damage. At eleven o’clock, the farmhouse residents’ nerves were frayed. They piled into two cars and fled to Hopkinsville for help.

By the end of the week Madisonville Road, which ran next to the Sutton property, was jammed with cars parked haphazardly and pedestrians picking their way along the drainage ditches. The local police, state police, and reporters from Kentucky, Indiana, and Tennessee were mounting simultaneous inquiries. Sightseers and investigators tromped around the farmhouse, marveled at the shattered windows, gathered bullet casings and snapped twigs from the trees where the creatures had perched.

All this might imply that the Hopkinsville incident was utterly novel—but it wasn’t. Extraterrestrial encounters were common fare in the media of the early Cold War. What is interesting about Hopkinsville is not that it was unique, but the ways Americans in general, and the residents of Hopkinsville in particular, made the incident an expression of their anxieties.

The eight years between Billy Ray Taylor’s sprint back to the Sutton’s farmhouse and 1947’s widely reported crash of a mysterious object outside Roswell, New Mexico, was full of sightings of odd flying objects and occasionally of their pilots. Reflecting the optimism of the early nuclear age, a good number of these experiences portrayed these extraterrestrials as comical, or even friendly. A journalist named Frank Scully wrote a book claiming that aliens dressed in “the style of 1890” had been recovered from a saucer crash in the Mojave Desert in 1949. The Californian George Adamski claimed that in November 1952 a cigar-shaped spacecraft landed near his campsite in southern California. Its occupant, a tall blonde Venusian named Orthon, promised to help Adamski save the human race from self-destruction, and by the mid-1950s Adamski’s books were selling thousands of copies and inspiring conventions across the world.

But as the Cold War heated up, Adamski’s optimism seemed increasingly naïve. In 1952, concerned enough to take this sort of thing seriously, the Air Force began Project Blue Book, an investigation designed to determine whether unidentified flying objects posed a national security threat. Certainly, for the Suttons and those who believed them the little green men showed how terrifying technology could be. In her book about the event Geraldine Sutton Stith, Lucky Sutton’s daughter, wondered whether it was a “coincidence” that UFOs began to be sighted “after we dropped the bomb.” Her telling of her family’s story emphasizes one of the signature fears of the Cold War: shadowy forces beyond her family’s control disrupting their lives in ways they barely understood. “My daddy didn’t like how people treated him once the story got out,” Stith told the reporter Maria Carter. “People made fun of him. It was traumatizing.”

On the other hand, to much of the rest of America the Hopkinsville incident was mostly of interest because of what it said about Hopkinsville. At some point, a reporter seems to have, perhaps for the first time, uttered the phrase “little green men,” though they were neither green nor, as one contemporary investigator’s exhaustive account pointed out, were they men. The article intimated that the Suttons and their guests had been drinking. More damningly, an Air Force investigator dismissed the entire story, declaring that the Suttons had spent that Sunday at a “Holly Roller Church” and hence “were worked up into a frenzy, becoming very emotionally unbalanced.”

For the media and the Air Force, the real threat was not the aliens; it was the backward people of Hopkinsville, bound up in country moonshine and rural religion.

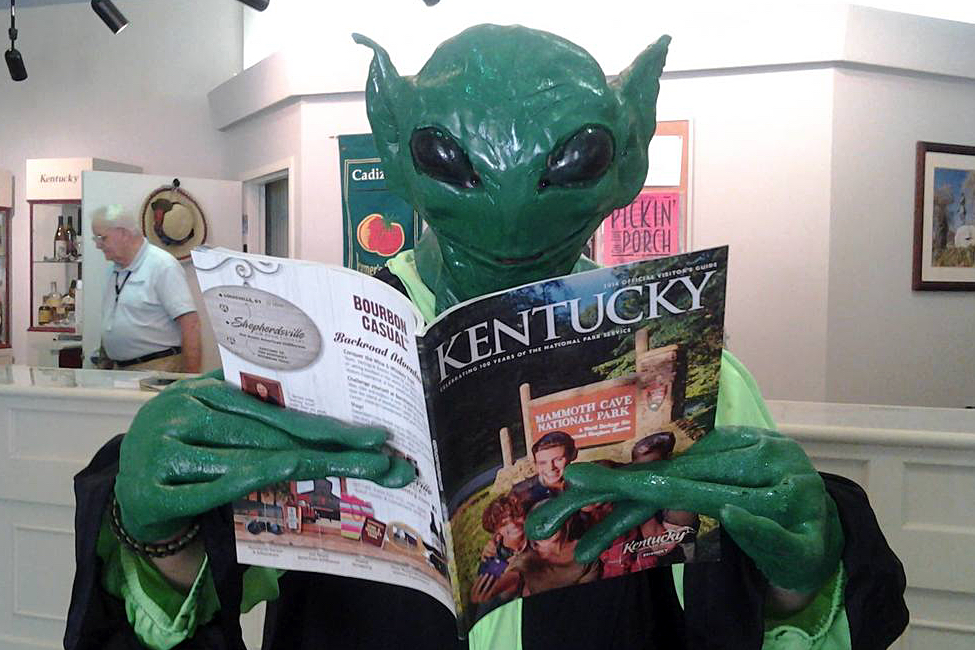

In 2010, Hopkinsville attempted to reclaim the story. The same city fathers promoting Eclipseville inaugurated Little Green Men Days, an annual festival held the weekend closest to the 21st. This year Little Green Men Days extends until Monday the 21st, intentionally linking the eclipse to the Sutton’s experience. Each year, Geraldine Stith retells the story in advance of a series of concerts, vendor shows, food truck parties, and the screening of movies like E.T.: The Extraterrestrial.

In 2010, Hopkinsville attempted to reclaim the story. The same city fathers promoting Eclipseville inaugurated Little Green Men Days, an annual festival held the weekend closest to the 21st. This year Little Green Men Days extends until Monday the 21st, intentionally linking the eclipse to the Sutton’s experience. Each year, Geraldine Stith retells the story in advance of a series of concerts, vendor shows, food truck parties, and the screening of movies like E.T.: The Extraterrestrial.

For a festival celebrating such an odd affair, movie screenings and food trucks seem decidedly conventional—which is exactly the point. It’s possible to read Little Green Men Days as a trial run for the eclipse; an attempt to rewrite a host of painful and bizarre narratives in ways that make the city stronger. The weird creatures that stalked the Sutton farmhouse stand transformed into mascots for Hopkinsville’s business community, and the eclipse is converted into a massive three-day weekend sale.

Indeed: at the very moment the sky begins to darken and everybody begins to look searchingly upward, there is scheduled a raffle for a new Mitsubishi…Eclipse.