What inspired you to write Virgin Nation?

I’ve been familiar with evangelical purity movements since I was an evangelical teenager. When I was young, “Why Wait?” by Josh McDowell was the only national program available—everyone was watching this VHS series in Sunday School or Youth Group.

One girl at my Christian school wore a shirt that said “I’m NOT Doing It” and listed all the bad things that could happen if you had sex. I myself wrote a letter to my local newspaper that had run a story about how teaching sexual abstinence was not realistic. I, the ever-zealous—and completely naïve—young evangelical, argued otherwise and offered myself as an example of teenagers who believed it wasn’t right to have sex.

So though there weren’t yet opportunities to take pledges and wear rings, I made a point to publicly declare my commitment to sexual abstinence before marriage.

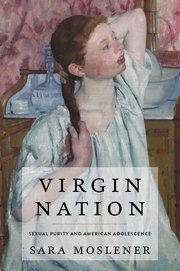

Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence

Sara Moslener

Oxford University Press

(July 1, 2015)

The main speaker was a young woman named Giana Jessen who promoted the value of sexual purity by describing her mother’s experiences as a pregnant adolescent. Her mother had attempted to abort her child and had failed. A nurse at the hospital rescued the child who, it turned out, was Jessen herself. By this time I no longer affilliated with the evangelical tradition and harbored deep suspicions about their tactics and theological assumptions. Hearing Jessen’s story and being part of the context in which it was used became a memory that practically etched itself in my skin.

Her story was something I needed to make sense of, and as the years wore on it became a heavy ghost that seemed to follow me everywhere.

It took me a while to formulate the questions I needed to ask about the history of evangelicalism, gender, and adolescent sexuality—and eventually a graduate school course would allow me the resources and opportunity to look into them. The project took on different shapes as a course paper, doctoral dissertation, and eventually Virgin Nation. I had to be talked at the dissertation stage by my advisor, whose prodding was instrumental in giving me the courage to move forward given my own past affiliation with the movement.

I’m a big believer that most academics are really writing their own stories. The more authentic we are with those stories, the more people connect to the histories we are trying to uncover.

Researching this history was a practice in chasing and catching those ghosts that seemed to haunt my life as a young adult. The timing for Virgin Nation is serendipitous to say the least. There are now many people who have passed through the purity culture and are telling their own stories of reclaiming their bodies, their sexuality, their relationships. Virgin Nation is a project in that same vein—though that may only be evident to those who know me well.

Researching and writing this book was a way to give flesh to those ghosts, to exorcise the spirit of the over-zealous, evangelical teen. I turned out to be a historian, so that’s the medium I am able to make use of.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

Sexual purity movements, past and present, are not ultimately about promoting a biblical view of sexuality. They are about explaining large-scale culture crises (e.g. Anglo-Saxon decline, the Cold War, changing gender roles and sexual mores) and providing a formula for overcoming those crises.

Today’s movement is laden with a therapeutic rhetoric that presents these choices as the best choices for those who seek to conform their behaviors to God’s will. It promises that those who conform will enjoy spiritual, physical, and emotional satisfaction in their marriage relationships. Other scholars have parsed these claims in more sophisticated ways than I do and many other writers have demonstrated that these expectations are anything but a path to personal well being. What I’m saying is that sexual purity has never been about personal well-being for evangelical adolescents— or anyone.

Each historical example I analyze demonstrates that purity work and rhetoric has emerged at moments when socially conservative evangelicals seek to assert and maintain their political power. Sexual purity isn’t about what Abby and Brendan do on a Friday night, it’s about constructing a view of the United States as a nation in distress and claiming that evangelical Christianity can not only best explain the crisis, but save us from our demise.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

For a long time I considered writing an addendum about post-purity evangelicals. This is a concept introduced by Abigail Rine who wrote in The Atlantic about the growing number of evangelicals and former evangelicals who’ve been recounting their experiences with sexual purity. Many of these are women who are writing through their own struggles with sexual shame as a result of learning at a very young age that sex was threatening to their physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

What’s emerged, especially in the work of women like Rachel Evans Held, Sarah Bessey, and Dianna E. Anderson, is a new strain of Christian feminism. And that’s significant. Really significant. It needs a book of its own. In the end, I had to be the academic and recognize this narrative didn’t help me to establish the argument I was making about national security.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

When I’ve given talks there is always someone who is expecting me to make a prescriptive statement about the movement. That is, they want to know if I support it or revile it. I was even asked this question at my dissertation defense. On the one hand, I’m pleased, because it means readers can’t necessary tell what my own biases are. While I do have an opinion on this, my opinion is not the same thing as my book’s argument—which is supported with evidence and argumentation.

My work as an historian is to describe what is, not prescribe what should be. The goal of Virgin Nation is to examine the cultural and political work done in the name of sexual purity. Whether you believe that work is the salvation of America or the root of all sexual tyranny, the book offers an important historical perspective.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

I’ve always had official and unofficial audiences in my mind. Primarily, I think about other scholars working on questions of religion, sexuality, and adolescence. Being part of a conversation about these topics has always been my goal. And I hope that my colleagues are able to use Virgin Nation to conduct their own conversations with students and readers.

My unofficial audience is the group of people I mention above. Those who, like me, have been working to reclaim their adolescence from the fear-based rhetoric of the movement.

(Before I ever started this project I watched Randall Balmer’s interview with Josh McDowell in Balmer’s video series, Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory. In that interview Balmer asks McDowell if it might be problematic to use fear to teach evangelical teenagers about human sexuality. McDowell responds that it’s extremely important to utilize fear because the alternative to heeding the message is so much worse. All this to say, when I use the term “fear-based rhetoric” this is not pejorative, but descriptive of the deliberate strategies used by the contemporary movement.)

Though not everyone turns to history to put their mind at ease, I find that when I can articulate the origins of something that has deeply impacted my self-understanding, I am more at home in my own mind and body.

Are you hoping to inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

I leave that up to the reader, because each one will have a response based on the set of questions they bring to Virgin Nation. Some will have questions from their own lives, others will have questions related to their own academic projects. As a scholar-teacher, my goal is always to educate and inform. That’s not unimportant work, especially when making sense of issues that deeply impact how we feel about our bodies and sexual choices.

What alternative title would you give the book?

I love the title and can’t imagine what else I could call it.

How do you feel about the cover?

Oxford University Press made this decision and I was more than delighted with it. I had initially suggested artwork by Norman Rockwell—a cover of The Saturday Evening Post that showed a young girl in white looking into a mirror with a film magazine on her lap. In the corner was a headline for another article—“The GI’s Who Fell In Love With the Reds.” The juxtapostion of that headline with the image was the perfect illustration of my argument about sexuality and national security.

OUP was also excited about this image, until they encountered too many obstacles in getting the rights. I’ve always loved Mary Cassatt’s paintings and it’s an honor to have my work associated with one of her pieces.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written?

I wish I had written The Courage to Teach by Parker Palmer. More precisely, I wish I could embody the authenticity and kindness in my own teaching that Palmer describes. This book helped me a lot in graduate school when I was overwhelmed and disillusioned by academia. It helped me remember who I was in the midst of feeling like I would never be good enough for this work.

Ironically, I read it before I ever started teaching. That was a rude awakening and I quickly recognized what Palmer meant by courage. Maintaining authenticity, kindness, vulnerability—all things that make a great teacher, these are almost impossible to achieve in the classroom. That is, you can’t make the teaching moments Parker describes happen with only rigorous course preparation and by being the expert in the room. But this is what students expect and what we’ve come to expect of ourselves.

I live with the constant tension that what is most expected of me as a teacher is not necessarily what makes for good teaching. This is the paradox that Palmer helps his readers to navigate—and I wish I had that ability.

What’s your next book?

I’m looking more closely at the racial origins of sexual purity. Right now I’m interested in the debate between the 19th century reformer Frances Willard and the journalist and anti-lynching activist, Ida B. Wells. Wells made it known that lynching in the late 19th/early 20th century was justified by the myth of the black, male rapist. Most lynchings occurred because black men were accused of raping white women. Wells’ investigation into hundreds of lynching cases determined that most of the time when authorities discovered black men and white women having sex, it was consensual.

In short, she exposed that white women not only sought to have sexual relations outside of marriage, they sometimes did so with African-American men.

Wells sought the support of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, but its leader, Frances Willard, would not give it because Wells’ argument was based on the truth—that women were having sex across the color line. Willard believed that white women’s sexual purity was the source of their religious and moral authority. Conceding Wells’ claim would have jeopardized Willard’s own authority and the Victorian gender roles that shaped so much of late 19th century culture and promoted Anglo-Saxon superiority.

The public debates between Wells and Willard raise important questions about how sexual purity policed both women’s sexuality and the color line. As I discuss in the first chapter of Virgin Nation, sexual purity was the means by which Anglos achieved and maintained racial purity. My hope is to find other places in US history where race plays a significant role in the promotion of sexual purity and see what else we can learn from them.