Though dreaded Taliban leader Baitullah Massoud may have been killed, the Taliban is still very much in control. Though this might seem like a time for US military forces in the region to celebrate, it is also a good time to assess what its mission should be in a post-Massoud Pakistan.

The strike by an unmanned US drone in Waziristan appears to have destroyed one of Pakistan’s most feared insurgents; the man who was likely behind the assassination of former Prime Minister Benezir Bhutto along with hundreds of other Pakistanis and Americans, including rivals to his authority. He was ethnically Pashtun, like most Taliban, and part tribal leader and part thug. But one thing he was not: a religious leader.

Though the Taliban in Afghanistan is identified with a strident Islamic political ideology, the truth of the matter is that very little of the Taliban leaders’ authority is based on religion. The ties to al Qaeda are thin, especially among the Pakistan Taliban. Most of the leaders are warlords and opportunists, and much of their support comes from a combination of intimidation and fear of outsiders. The US military presence, alas, contributes to this paranoia and helps to shore up the very movements that it is trying to destroy.

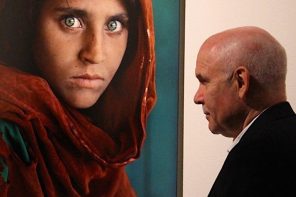

Like the North Vietnamese, many Afghan activists—and an increasing number of Pakistanis—are motivated to fight against the American presence because of their love of freedom. They see the US military, like the Soviet forces before them, as a foreign occupying power. The Taliban, as draconian as they may be, are seen as enemies of the enemy: us. It is the US military presence, paradoxically, that is uniting the Taliban and marshaling wide public support behind it.

What all this means is that a military strategy simply will not win. A new policy is in order. Recently we convened at Santa Barbara a workshop of senior scholars of South Asia studies in the United States, and asked them to evaluate the US role in South Asia. The scholars agreed upon the following five principles as the bases for formulating a new US policy:

1. Support self-determination. The Obama administration needs to make clear that the people of the region shall decide their own future, and the United States or any outside power can only play a modest role in helping that process. It cannot control it. Many people in the region see the US presence in South Asia as a continuation of British colonial influence. The parallels with Vietnam are striking: in Vietnam the United States also appeared to be replacing a colonial power, the French. Many in Afghanistan see the US military as a curious repetition of yet another military intruder, in this case the Soviets. Though the US policy might intend to help fight terrorism in the region, the very presence of US forces helps to create the climate of hostility in which anti-American terrorism can thrive.

2. Demilitarize. As President Obama has said, there is no military solution in the region. But this could be taken to mean that the military approach, though necessary, is not sufficient. Our point is that the military presence itself is counterproductive. The very size of such a huge US military build up creates antagonism towards the United States. A recent opinion survey conducted by the New America Foundation showed that 44% of the polled Pakistanis regarded the United States as their principal adversary; only 14% considered it to be India, 8 % the Pakistani Taliban, and 4% the Afghan Taliban. A process of demilitarization will help to reverse the pervasive consequences of US military presence in political, economic, social, and cultural spheres, and the enormous antagonism this has generated among the local people of the region.

3. Recognize the religious and organizational diversity. The Taliban is not a single unified organization. There are more than twenty different groups operating in the name of the Taliban in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Some are tribal groups, some are ideologically religious, some are thugs; but until recently all have been ethnically Pashtun. Some elements have made alliances with the Punjab-based militant groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (connected with Kashmir insurgency and accused of the Mumbai attacks). But there are many branches that reject this jihadi ideology. Even within the more moderate religious groups there is a great deal of diversity. Besides Shia and Sunni streams, there is a long tradition of Sufi practices in the subcontinent. Within the Sunnis there are differences between the Deobandi school and the Baraelhi schools, which interpret Islamic law differently. Some Muslims are members of the Ahmadiya sect and some adhere to other religious traditions. There are native Sikhs in Swat valley who have been attacked by some branches of the Taliban, and Sufi shrines in many areas have been condemned widely. So it would be a mistake to regard forms of Taliban as the same, or all religious groups as the same. Some will never negotiate, but others are open to cooperation and change.

4. Respect the legitimacy of religious politics. Among the many forms of religious politics in the region are quite a few that are democratic and tolerant. The rise of religiously-related political movements is not necessarily to be feared; nor are they antithetical to democratic values. One of the great nonviolent leaders of South Asia’s independence movement, Ghaffar Khan, was known as the Pashtun Gandhi. For centuries Muslim courts in the region provided the civil structures of justice and order that are the hallmarks of a decent society. For many people in the region, the longing for a religiously-based political rule is simply a way of stating a desire for morality in public life, and forms of government that are just, fair, and high-minded in their values.

5. Be open to regional solutions. When local governments are not able to resolve situations, regional solutions—rather than international military intervention—might be used. One such organization is the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation, in which India plays a dominant role but the group also includes Afghanistan along with Pakistan. Equally relevant is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), consisting of China, Russia, and four Central Asian countries; Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and India have membership as observers. At a recent meeting of the SCO, Russia proposed an interesting solution to stabilize the Afghanistan security situation: it would activate the UN Contact Group on Afghanistan and expand it to include its six neighboring countries along with the United States, Russia, and NATO. It is important for the United States to respect such initiatives and work with them to encourage progress along regional lines.

The key to this five-point framework for US policy in the South Asia region is to demilitarize the US presence while utilizing its influence for regional cooperation and viable self-determination. The politics of the region may not always mimic the kind of secular politics with which we are familiar in the West, but it may be capable of more latitude for justice and fair play than the strident versions of politics that the Taliban have presented. A supportive non-military US engagement in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India in a new era of global cooperation may help to bring peace to the region and provide substance to President Obama’s promise of “mutual interest and mutual respect” among the peoples and countries of the world.