What inspired you to write Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich?

Since I was a kid I’ve been interested in the supernatural: vampires, werewolves, horror films, and classic E.C. comics; Poe, Lovecraft, Anne Rice, and Stephen King; superheroes, like Batman, Wonder Woman, Captain America, or Indiana Jones, who battled Nazis. As a historian of the Third Reich, it’s hardly surprising that I became curious about the reality behind this popular image of occult-obsessed, Grail-chasing Nazis. When I finished my last book (Living With Hitler: Liberal Democrats in the Third Reich), the supernatural history of Nazism seemed like a logical next project.

The inspiration for Hitler’s Monsters was, like Living With Hitler, in some respects contemporary. I began researching Living With Hitler in the early 2000s, in the wake of 9/11 and the Iraq War, when many American (and British) liberals appeared to be making cynical concessions to the forces of nationalism, imperialism, and autocracy. I wanted to understand why liberal-minded German Democrats appeared to make even more problematic concessions in the 1930s and 40s. Hitler’s Monsters was inspired, similarly, by contemporary questions: namely, in what way did supernatural, conspiratorial, faith-based thinking and an aversion to science and empiricism help facilitate “alt-right,” racist, illiberal, anti-democratic politics?

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

The message is that the Third Reich would have been highly improbable without a widespread penchant for supernatural thinking—exacerbated by military defeat and social crisis—which Hitler and the Nazi Party rushed to exploit. Nazism was not the first movement to take advantage of people’s faith for political purposes. But Hitler and the Nazi Party was far more effective than other parties in drawing upon what I call the “supernatural imaginary”—a cluster of occult and border scientific doctrines; Nordic mythology and Germanic folklore; pagan, New Age, and völkisch religions that attracted a generation of Germans battered by war, violence, and sociopolitical dislocation.

In the Epilogue I suggest that today, as in Germany a century ago, there is a renaissance in border scientific, faith-based, conspiracy-driven reasoning, which has begun to correlate with illiberal political and ideological convictions, influencing national elections, domestic social policies, and matters of war and peace. I believe this phenomenon is evident globally, whether in the emergence of neo-fascist (“alt-right”) groups across Europe and the United States or in the exponential growth and politicization of fundamentalist Islam and Christianity. Every culture has its own supernatural imaginary that can, in times of crisis, begin to displace more empirically grounded attempts to solve challenges that define our 21st century reality. It is only by acknowledging the historical pervasiveness and consequences of this kind of supernatural thinking—in the Third Reich and elsewhere—that we might work to counter its influence.

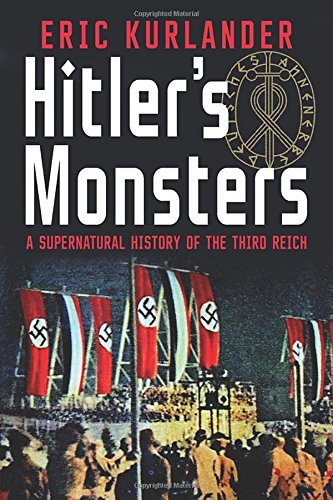

Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich

Eric Kurlander

Yale University Press

July 2017

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Given word counts and the need to maintain narrative coherence, we can never hope to reproduce the full panoply of historical experience, in all its complexity. There are many strands of research that could be followed up in more detail: for example, the widespread interest in pendulum dowsing, from Hitler and Himmler to the German Navy. One could also write a scholarly biography of the SS occultist and Himmler confidant, Karl Maria Wiligut; the pro-Nazi, Jewish clairvoyant Erik Hanussen; the paganist, anti-occultist Mathilde Ludendorff (spouse of the occult-inclined Field Marshall Erich von Ludendorff); the SS Grail Researcher Otto Rahn (the “real Indiana Jones”); or Special Operations leader, Mussolini rescuer, and Werewolf leader Otto Skorzeny—all of whom make appearances in my book, but never get first billing. Or a collective biography of pro-Nazi occultists such as Karl Krafft, Hans Bender, and Wilhelm Wulff, which I only discuss intermittently. At the same time, I feel I’ve included at least the most interesting instances involving these individuals as well as other majors themes—from the esotericists, paganists, and horror writers who helped the Nazis into power and influenced their views on religion, politics, and society to the vampires and werewolves that informed their views of partisan warfare; from the “border sciences” influenced Nazi policies of race and space to the preoccupations with miracle weapons and Götterdämmerung that defined their experience of war and defeat.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

The first is that nearly everything that can be written about the Third Reich has already been written. Because of the vast and influential nature of Germany both before and during the Third Reich; because of the sheer scale of the Second World War; and because of the unprecedented number of documents preserved in hundreds of archives and libraries across dozens of countries, this is obviously not the case. The second is that there’s little to no reality behind popular cultural representations of the Nazi supernatural. While many of these representations are exaggerated or erroneous, many others have some basis in reality. In the case of Hitler’s Monsters truth really is stranger than fiction.

The first is that nearly everything that can be written about the Third Reich has already been written. Because of the vast and influential nature of Germany both before and during the Third Reich; because of the sheer scale of the Second World War; and because of the unprecedented number of documents preserved in hundreds of archives and libraries across dozens of countries, this is obviously not the case. The second is that there’s little to no reality behind popular cultural representations of the Nazi supernatural. While many of these representations are exaggerated or erroneous, many others have some basis in reality. In the case of Hitler’s Monsters truth really is stranger than fiction.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

Whether they admit it or not, historians always want to reach—and impress—two audiences: their fellow scholars and the lay public. This is not easy. Scholarly disciplines have never been more specialized and the competition for grant money and publication more difficult. But if one wants to reach a wide public, one has to strike the right balance between historiographical complexity/originality and accessibility, between exhaustively documented, archival-based primary research and a story-driven narrative unencumbered by too much nuance or detail. If I’ve erred a bit toward scholarly documentation, it is because the topic really deserved serious inquiry. I still worked to make the narrative and argument as accessible as possible. I hope that I have pulled it off.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

One always wants to inform readers. Entertainment is fine as a secondary goal. And it’s the role of all good scholarship to provoke critical analysis and revision of existing interpretations (although I don’t think any of us is consciously trying to piss anyone off). But my primary goal has been to write the first “supernatural” history of the Third Reich, encouraging scholars to ask new questions and pursue new lines of research, whether they agree with my conclusions or not.

What alternative title would you give the book?

Early on the working title was Consuming Terror: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich. It was based on my hypothesis that the Nazis used “horror,” “terror,” the fear of a “monstrous” other to attract popular support and pursue their domestic and foreign policies. After a year or so of research I changed the title and approach because it was too narrow. It didn’t pay enough attention to the sheer richness and complexity, the depth, breadth and authenticity of supernatural thinking in the Third Reich.

How do you feel about the cover?

I really like it. We started with some literally monstrous images and then pared it back to this more evocative, perhaps even darkly ruminative cover.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

Wow, there are so many. In terms of this particular theme, my former Harvard colleague Corinna Treitel’s A Science for the Soul is an exceedingly well-researched and elegantly written account of German occultism from the 1870s through the 1940s. More generally, another recent book that impressed me in terms of ambition and argument was Kris Manjapra’s The Age of Entanglement: German and Indian Intellectuals Across Empire. It’s a model of transnational scholarship, but also makes a number of fascinating claims regarding the mutual cultural and intellectual affinities among German and Indian intellectuals.

What’s your next book?

I’m currently co-writing for Oxford University Press a book titled Modern Germany: A Global History, 1500-present. What makes the project interesting to me—and hopefully our audience—is that we’re trying to tell the history of German-speaking Central Europe by taking a transnational and global approach. While there’s a lot of great academic research on individual aspects of German history from a global and transnational perspective, we have no narrative history that attempts to incorporate these themes and perspectives over the longue durée.

A second project, which is only in its early stages, has the working title, Before the Final Solution: A Global History of the Nazi “Jewish Question.” I would like to investigate the ways that the Nazi “Jewish Question” was conceived before the Summer/Fall 1941, when Hitler, Himmler and company implemented the “Final Solution.” Scholars recognize that the idea of “solving” the putative “Jewish Question” through non-exterminatory means preceded the Third Reich and the Holocaust (“Final Solution”) by many decades, involving numerous European states and multiple so-called “solutions.” Some of these “solutions”—such as transporting the Jews to Palestine or Madagascar or creating a Jewish “reservation” in Poland—were eventually taken up by the Nazis, only to be discarded a few months or years later. How close were these solutions to succeeding? Which states, actors, and events played a role in facilitating (or preventing) these earlier “solutions”? How and why did they fail? What does this say about broader patterns of ethnic cleansing and the role of global and transnational factors/actors in solving ostensibly local nationality and refugee “questions”?