Ana Marie Cox recently noted in The New Republic that conservative legislators in Florida and Texas have been resurrecting doctrines from the original Drug War that would permit authorities to prosecute even mild participation in drug use, such as handing someone a syringe, as a poisoning homicide. Cox is correct to point out that “poisoning” was a trope of the early Drug War but, along with many professional historians, there is one detail her article gets wrong. Although Nixon is often credited with starting the Drug War (and he did in fact escalate federal antidrug efforts) it actually predates him by at least a century; the phrase “War on Drugs” was even in use by the 1910s.

Christian Nationalism and the Birth of the War on Drugs

Andrew Monteith

NYU Press

July, 2023

Temperance reformers felt frustrated that nineteenth-century dry laws tended to flounder or fail and that their attempts to convince drinkers to quit went unheeded. They were also coming to terms with the idea that even people who sincerely wanted to quit sometimes found it impossible. In response, reformers like Frances Willard and Mary Hunt were moved to innovate. If drunk adults would not or could not make the moral choices necessary to save the nation, well, the Kingdom was a long process; maybe intervening in children’s morality with Temperance Education could get them where they wanted to go.

Temperance Education assumed the dominant educational norms that approached schooling to be at least partly about character formation. Prescribing specific religious tenets or ritual practices might be off-limits, but the ideals and virtues that every Protestant could agree on were an important function of public education. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), aware of the discomfort some Jews and Catholics felt about their Protestant moralism, chose to insert their alcohol positions in public schools through “Scientific Temperance.”

Their lobbying was successful and they got municipalities, states, and even Congress to mandate that children learn from WCTU-approved materials. Textbook companies adapted their texts to meet the WCTU’s standards for what passed muster as proper Temperance Education, uniformly taking positions that marked alcohol, opiates, and tobacco as damaging, morality-eviscerating substances, sometimes taking shots at caffeine and spices too. The WCTU wanted two things from this: to reshape children’s morality so that they would abstain from drinking as adults, and to shift the public opinion of the next generation to one that supported Prohibition. They may have strategized smartly. The kids they taught to be anti-alcohol were indeed the generation that added the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution.

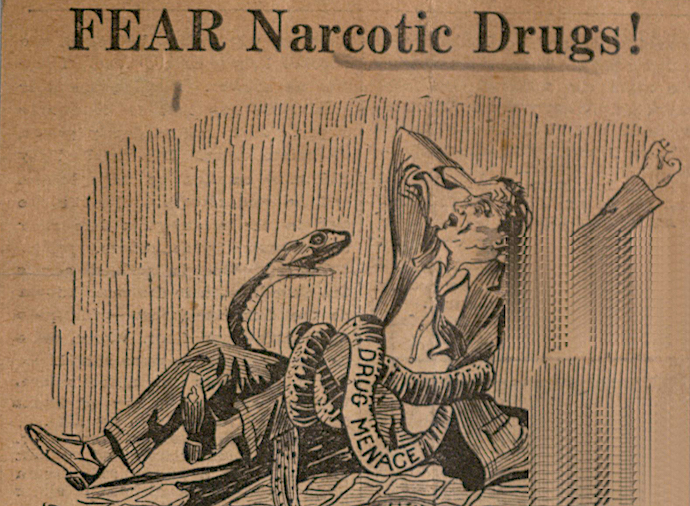

Temperance Education and a rising moral panic about narcotics contributed to new antidrug regulations. Alcohol may have been the WCTU’s primary enemy, but the changing ideas about addiction and how it worked began merging with 1880s racial fears in new ways. Chinese immigrants in particular were suspected of opiated lechery, luring White women to their dens in exchange for narcotic slavery. By the turn of the century White Americans were also beginning to fear Black cocaine use. Some Southern police departments went so far as to upgrade their bullet caliber from .32 to .38 in response to fears that Black men on cocaine couldn’t be stopped with anything smaller.

News media promoted many of these narratives, repeating story after story after story about Black or Asian men debauching naïve White teenage girls. What emerged was a racial-religious threat. The dominant narrative treated the United States as a White Protestant nation chosen by God to bring about the Millennial Kingdom, a destiny threatened by the iniquity, degeneracy, and crime of racial others.

Of course the media rarely made such explicitly religious claims and it’s likely that many journalists weren’t preoccupied with the Kingdom. Many of those writing about immigrants or Black men debauching White women may have understood themselves to only be telling what they thought was an interesting and true story. It would also be remarkable if many of them zoomed out to recognize their articles as just another derivative piece of racist dogma.

But what individual journalists understood their work to be and what that work meant to readers are different things. Race can’t be sectioned off from the rest of culture any more than religion can. To readers coming from a Protestant postmillennialist outlook—which in this period would have been the hegemonic position—racialized drug use was an obstacle (or perhaps even existential threat) to their utopian dreams about Whiteness regardless of whether or not newspapers framed articles in White Christian language.

Contemporary readers may find abortion to be a helpful analogy here. A neutrally worded article about medical abortion practice might never mention anything religious within its content, yet a conservative Christian reader in the United States today is likely going to see religious significance in the article nonetheless. Protestants consuming media about substance use a century ago similarly saw significant religious implications whether journalists wrote about it that way or not.

The antidrug campaigns of Rear Admiral Richmond Pearson Hobson, an influential Prohibitionist, short-term congressman, and Spanish-American War hero, worked to mediate the relationships between antidrug media, public opinion, and law. They were also motivated by private Protestant concerns. Although Hobson considered America to be authentically welcoming for people of other races or religions, such welcome was an extension of Christian charity from a Christian nation. God was forging a new White race out of the United States, which was destined to lead the world toward the promised Kingdom. American destiny was not a sure thing, however—it was God’s offer, not his guarantee.

Hobson was partly influenced by phrenology—a nineteenth-century pseudoscience that claimed to know individuals’ personal character and abilities based on brain physiology (outdated even in his own time)—as well as degeneracy theory, which was cutting edge science in the early twentieth century. Medical theorists had long suggested that substance use of any kind degraded and degenerated individuals’ biological capacity for morality in catastrophic ways. Alcohol, opium, cocaine, peyote, and cannabis took otherwise good people and made monsters of them. By the twentieth century degeneracy theory had evolved into eugenics, a kind of scientific racism with serious implications for American culture, law, and moral norms.

While degeneracy theory was considered valid science in the early twentieth century, Hobson’s narration of this was often sensational. For instance, during the 1912 “Men and Religion Forward” movement—a national revival aimed at promoting the kingdom—Hobson shared the stage of the Brooklyn Tabernacle with Booker T. Washington and claimed that African Americans would degenerate into cannibals if they were permitted to drink alcohol. Christians, he felt, needed to lead the world toward sobriety through law, through example, and through education.

Hobson’s take on drugs was quite similar. After Prohibition passed, Hobson viewed narcotics as the next contagion to clear from America. He believed that addicts stole, murdered, and “converted” others into addiction—including schoolchildren—and that shadowy international drug cartels were deliberately trying to undermine American security through child addicts. Hobson reflected on the WCTU’s anti-alcohol strategies and successfully reproduced them. He saw public opinion and education as the engines that drove America toward Christian progress, yet like Mary Hunt he backed away from publicly framing his mission as specifically Christian.

As he explained to General John J. Pershing (briefly one of Hobson’s allies), antidrug “propaganda should come from some special organization,” preferably one amenable to everyone regardless of political party, religion, or nationality. Hobson established and appointed himself head of multiple antidrug organizations aimed at this goal, successfully positioning himself to lobby media, launch public demonstrations, to work closely with legislators to craft and pass new antidrug laws, and to orchestrate antidrug education.

Hobson left a considerable legacy. Narcotic laws are easier to create than they are to revoke. Today, drug offenses are by far the largest conviction category for federal prisoners—more than double that of the second-largest (violent crimes). The first waves of truly punitive drug laws emerged in the 1920s and 1930s during the moral panic that Hobson was quite intentionally trying to produce. It’s true that he considered addicts pitiable slaves, yet he also thought they were extraordinarily dangerous. It was easy politics for legislators to ally with his cause. And indeed, many of the meaningful early laws—the ones with prison teeth—were enacted at state levels in this era.

He also helped propel the moral discourse that would come to characterize the later stages of the War on Drugs. Other historians have often attributed this to Harry Anslinger, who was admittedly important, openly racist, and avowedly punitive in outlook. Anslinger wasn’t charismatic, though—he was a crotchety bureaucrat working for the Department of Treasury. It’s impossible to say how things would have progressed had circumstances been different; perhaps Anslinger would have gotten the national conversation about drugs and addicts to go the direction it did. Yet when Anslinger came into power at the Federal Bureau of Narcotics Hobson had already been working the press, the schools, and the reform movements for nearly a decade, using his fame and charisma to convince Americans that drugs were a crisis. Anslinger teamed up with Hobson to repeat the same mantra: Addicts threatened to destroy America’s entire social reality.

Education may have been Hobson’s most important intervention. Millions of American schoolchildren grew up in the 1920s and 1930s with “Narcotic Education Week,” using textbooks that emphasized how bad drugs could be for destroying morals, health, and respectability. A widespread narcotic panic in the media, the political realm, and churches accompanied schools’ antidrug messaging. Nearly every radio chain—NBC, CBS, etc.—gave Hobson and his friends a microphone. Although it’s been forgotten about today, Narcotic Education Week was wildly successful by the early 1930s, earning praise from sources as diverse as Franklin Roosevelt, Benito Mussolini, the Vatican, and literary icon Rabindranath Tagore.

While people evolve and adapt throughout their lives, childhood and adolescence are important periods for psychological formation. It’s the first stage where we learn what kinds of behaviors are valued and what kinds are discouraged; what responsibilities we have to others and what kinds of activities people should be held accountable for. If the generation that grew up with Temperance Education (at its height between 1883 and 1906) went on to pass Prohibition in 1920, we might pause to question what the Narcotic Education Week generation (1923–1937) went on to do 30–40 years later.

The 1960s and 1970s brought a wave of new antidrug measures, many of which were stricter than what already existed, including the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. The 1960s media and legislative discourse repeated many of the Narcotic Education Week tropes: Substance use (which now included LSD) led to immorality, crime, and social disruptions; better education was needed; and only fools sought drugs in pursuit of the “illusory” goal of happiness.

It may surprise no one to learn that Richard Nixon grew up with Narcotic Education Week. Nixon went to grade school and high school in Whittier and Fullerton, both of which are in the Los Angeles metro area. He graduated high school in spring of 1930. Los Angeles was the heart of Narcotic Education Week and home to its earliest iteration; it would be shocking if Nixon never encountered it as a child. As president, Nixon amplified existing antidrug structures and reshaped national narratives, therefore it seems highly likely that he himself was influenced by Hobson’s work.

There’s more: 1920s–1930s Los Angeles was also home to Daryl Gates, perhaps best remembered for his role as police chief during the 1992 unrest over police violence against Rodney King. Gates was born in Los Angeles in 1926 and would have grown up with Narcotic Education Week too, which some parts of California were still observing even as late as 1939. Gates was also the creator of Drug Abuse Resistance Education, better known to many Americans as D.A.R.E. The D.A.R.E. program began in Los Angeles in 1983 and placed uniformed police officers in classrooms to teach children about substance use, eventually evolving into a national program. (Remarkably little critical scholarship has been published about D.A.R.E.)

Growing up in Indiana, I remember officers coming to my elementary school classrooms in the early 1990s to explain the horrors of drug use. We watched videos of teens jumping to their deaths through skyscraper windows. Officers described the moral tragedies attendant to marijuana and let us know that if anyone we knew used it, including our parents, we should turn them in. More than 30 years later I still recall those lessons; they are etched into my long-term memory.

But that enculturation has a genealogy. My D.A.R.E. officers participated in a national program largely designed by Gates who himself would have learned Hobson’s sensationalist variety when he was of D.A.R.E. age. And just as Gates’ program was the resurrection of Hobson’s campaign, Hobson’s program was the resurrection of Christian Temperance. At the end of the day, we’re still living in the shadow of our forebears’ morality. The Drug War is Protestant moralisms all the way down.

This adapted excerpt from Christian Nationalism and the Birth of the War on Drugs is published with the permission of NYU Press.