The state of Texas, which was subject to a landmark Supreme Court ruling today, is one of a handful of states requiring not only that abortion providers perform an ultrasound, but that they both display and describe the image to the woman before the procedure. In this essay, historian Elizabeth Yale looks at the extraordinary history of imaging the womb. – eds

***

In 1751, the anatomist William Hunter obtained the corpse of a woman who had died unexpectedly in her ninth month of pregnancy. Hunter, who would go on to become accoucheur (or, less respectably, man-midwife) to England’s Queen Charlotte, immediately set about dissecting the body, layer by layer. He employed an artist to draw the cadaver as he worked.

After this first lucky get, Hunter procured a series of bodies of women who had died during different stages of pregnancy. Twenty-three years later, he published a book, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, Exhibited in Figures, that offered the first naturalistic images of fetuses in utero, documenting the progression of pregnancy from the early weeks through the final month.

Fetal imaging is ubiquitous today, but until the 18th century the pregnant womb was largely inaccessible to visual inspection. Hunter’s atlas demonstrates how an imaging technology opens up pregnancy to new gazes—and, in doing so, how it shapes understandings of the personhood of both a mother and a fetus.

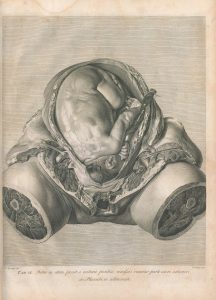

Hunter’s images are brutal, yet tender. A series of unnamed, headless, legless women shelter fetuses who are not assigned a gender. Each image is a portrait of a single pregnant uterus, rendered with precise detail.

Plate VI illustrates the torso of “a woman, who died suddenly, in the end of her ninth month of pregnancy.” The fetus is shown tightly cradled and folded, its back covered with a waxy, white coating of vernix, “commonly seen on children at their birth,” as Hunter explains. (The explanation of something that any practicing midwife would have taken for granted is a clue to the intended audience for this book.)

To prepare the specimen, Hunter cut away the woman’s exterior genitals and removed her bladder, the better to display the position of the fetus’s head. “Every part,” he writes, “is represented just as it was found; not so much as one joint of a finger having been moved to shew any part more distinctly, or to give a more picturesque effect.” An anatomist and an artist mapped the unique convolutions of the fetus’s ear, furled and mashed, but cut the mother’s legs off mid-thigh, rendering them like desiccated ham steaks.

“Artistic choice, as well as anatomical practice, reduced women’s bodies to their uteruses…“

Hunter’s language makes a claim to objectivity. In fact, Hunter’s particular anatomical and scientific interests shaped the “naturalism” of the images. As he worked, he prepared the cadavers to highlight and preserve certain features, even as he downplayed others. Hunter, particularly interested in the connections between mother and fetus, injected red and blue wax into the arteries and veins that ran through the placenta. The wax raised up these vessels, making it possible to trace the network through which the mother’s body nourished the fetus’s.

The weather imposed its own constraints: a body obtained in the chill of winter could be worked through more slowly than the body of a woman who died in the summer.

Artistic choice, as well as anatomical practice, reduced women’s bodies to their uteruses, emphasizing women’s object-likeness while enhancing the individual status of the fetus. Hunter dissected layer by layer, employing artist Jan van Rymsdyk to sketch the preparations at each stage. He reproduced these images for wider distribution using copperplate engraving. When printed, the resulting images were sharp, with finer detail than was possible with woodcuts, which earlier generations of anatomists had used to produce more schematic, idealized views of womb and fetus.

Hunter chose engraving specifically for the detail and clarity it made possible. Other options, which might have softened the harshness of his images, were available. His contemporary, J.N. Jenty, who also employed van Rymsdyk, published a treatise on the pregnant female body in which the illustrations were reproduced using the softer technique of mezzotint, creating gently shaded, rounded images. Folds of drapery obscured the cadaver’s meat-like edges.

In Hunter’s time, naturalistic images of the interior of the pregnant body were rare. Anatomists usually obtained cadavers from the gallows. The majority of hanged criminals were men, and, in any case, the state would never knowingly execute a pregnant woman. Rather, she was allowed to “plead the belly” until the baby was born.

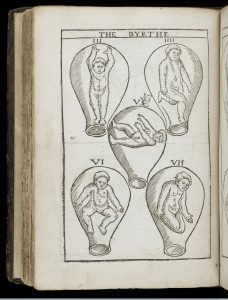

There was, however, a tradition of visualizing near-term fetuses as “babies in bottles.” These images, first printed in the German physician Eucharius Rösslin’s 1513 Rose Garden for Pregnant Women and Midwives, became the standard way of visualizing the interior of the pregnant womb in 16th and 17th century Europe. They showed a generic, adult-like baby in the series of positions in which fetuses were known to present at delivery: head down, feet first, knees out, raising the roof, and so on.

Hunter’s costly engravings opened up the development of the pregnant uterus to a medical elite. Rösslin, on the other hand, geared his manual towards women, especially midwives (it was read more widely, though—men were also curious about birth and generation.) Cheaply printed and soon translated from German into vernacular languages across Europe, the Rose Garden became a durable best-seller.

For midwives, the Rose Garden’s images fulfilled a practical need. Midwives (and other birth attendants) sensed the position of the fetus through touch. When a fetus presented in a position other than head down, a skilled midwife could, in some cases, use her hands to guide and reposition the fetus before and during labor. Midwives could study these images, and the accompanying instructions for turning a malpresenting fetus, to better contextualize the knowledge they obtained with their hands, as well as from other midwives. Birthing a child was understood as a spiritual experience as well, guarded about with prayer, and, at least among Catholics, with relics and other holy objects.

For obstetricians, Hunter’s engravings, repeatedly reprinted through the 19th century, replaced the “babies in bottles” as standard images of the interior of the pregnant body. As late as 1927, one obstetrician proclaimed Hunter’s atlas “the finest of its kind.” Simultaneously, male practitioners assumed more and more responsibility for midwifery care, which they relabeled obstetrics. Initially, man-midwives were summoned only in emergency cases, such as breech births and obstructed labors. Gradually, they gained command of uncomplicated deliveries as well, as women came to believe that male practitioners were more likely to see them and their babies through labor and delivery alive. Using legislation and licensing regimes, male physicians also worked to suppress female midwifery practice.

In the centuries following the publication of Hunter’s book, anatomical knowledge of pregnancy may have increased, but respect for women’s knowledge of their own bodies—knowledge held in the hands, rather than the eyes—declined. A 19th century obstetrician who praised Hunter’s anatomical talent wrote that, as a man-midwife, he trusted too much in “the powers of nature”—that is, in the power of the female body to accomplish the work of delivering a baby without medical intervention.

In our own day, images of pregnancy proliferate. Limbs emerge out of the floating darkness as an ultrasound technician traces a wand across a woman’s jelly-smeared belly. A heart thrums, and a parent can see it on the screen at six weeks, whereas a woman in the eighteenth century would not generally have confirmed her pregnancy until “quickening,” the moment at about twenty weeks when she feels the baby move for the first time. Expectant parents learn their baby’s sex—or have the technician write it down and place the slip of paper in an envelope, to be used to plan a “gender-reveal” party with a—surprise!—pink or blue cake. In comparison, Hunter betrayed no interest in the gender of the children housed in the uteruses he anatomized. Access to living images of the fetus facilitates our own obsession with gendering babies, even before their birth.

But imaging technology also introduces difficult questions. Twenty-five states have passed laws regulating the use of ultrasound imaging when a woman seeks an abortion. In Louisiana, Texas, and Wisconsin, the law requires an ultrasound (in the earliest stages of a pregnancy, this means a transvaginal probe) and stipulates that the provider must explain and describe the image to the woman. The law, in its gracious majesty, does allow the woman to look away as the physician probes her and describes the image.

When a woman intends to keep a pregnancy (and when she has access to prenatal care), physicians use ultrasound, along with other prenatal tests, to diagnose abnormal fetal conditions and developmental disorders. On the basis of this evidence, parents may decide to abort an otherwise wanted pregnancy.

These uses of ultrasound technology, though they serve different aims (one forcibly takes away a woman’s control over her body, the other is meant to encourage choice), both enhance the personhood of the fetus. An anti-abortion activist imagines that a woman viewing an image of a fetus will envision the child it might become—or already is, the activist would say—and decide against ending her pregnancy. Prenatal testing regimes, similarly, give a fetus an identity as a person. Is it a boy or a girl? Does it have all its limbs? Will it develop intellectually and physically roughly within the bounds of what medicine and society agree is “normal”? Can I imagine my life not with a baby in it, but with this baby?

“Both Hunter’s engravings and ultrasound technologies give body and identity to the fetus while reducing mothers to vessels.”

Hunter’s engravings prepared the way for the modern use of ultrasound, and they remind us that even the most objective-seeming images are selective in the scope and focus of their gaze. Both Hunter’s engravings and ultrasound technologies give body and identity to the fetus while reducing mothers to vessels. Yet, although Hunter cut the bodies of pregnant women down to their uteruses, he emphasized the connections between fetus and womb and the structure of the womb itself (roughly a third of the images show fetuses). In discovering the network of arteries and veins that linked mother and child through the placenta, he situated the child in the maternal body that nourished it. In the public mind, ultrasound technology downplays that linkage. Though the uterus and placenta are dimly visible in an ultrasound image, they are rendered with less detail, and we place the emphasis on the fetus, noticing the mother’s body only when something is abnormal.

An imaging technology’s impact on our views of fetal and maternal personhood is as much about the surrounding political and scientific context as it is about the technology itself. It’s easy to focus on the butchery in Hunter’s engravings—but that would mean disregarding his efforts on behalf of women—his “trust in the powers of nature.” For example, he advocated against the practice, common in France, of attempting to ease obstructed labors by cutting the pubic symphysis (this joint, which links the pelvic bones, stretches and relaxes during labor to allow a baby’s passage). Hunter applied his anatomical knowledge to show that this painful and debilitating procedure didn’t actually make labor any easier.

Similarly, ultrasound can be used to empower women or to punish them. The possibilities and constraints of an imaging technology may determine what we can see inside our bodies. But the political and scientific choices we make about how to use the resulting images determine the courses of our lives.

Also on The Cubit: The search for lost white tribes

Follow The Cubit, RD‘s religion-and-science portal, @TheCubit