José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, radical Puerto Rican activist and civil rights icon, passed away on January 10, 2025. He was 76. Best known for co-founding the revolutionary Young Lords—which began as a street gang and transformed into a political movement aligned with the Black Panther Party and the Rainbow Coalition—Cha Cha became one of the most recognizable Latino social movement leaders in the country. His life, activism, and radical politics paint a more expansive, more inclusive, and more revolutionary picture of the American civil rights movement than the one familiar to most.

Birth of a Young Lord

Jiménez migrated from Puerto Rico to the mainland at age two with his mother, Eugenia, once his father had saved enough money working as a farm laborer in the Northeast. The family moved to Chicago in the early 1950s, where his family—like too many other Latinos and other poor and working people in Chicago—bore the brunt of racial segregation and gentrification presented as “urban renewal” throughout the 1950s and 1960s. As a result of these efforts, Jiménez had attended three different schools by the time he reached third grade. When he reached junior high, his devoutly Catholic mother enrolled him at St. Theresa’s, a Catholic school in Lincoln Park. The priests and nuns there called him Joseph instead of José, a common experience for many young Latina/os in the U.S. whose names were anglicized in school as part of larger Americanization efforts in the twentieth century.

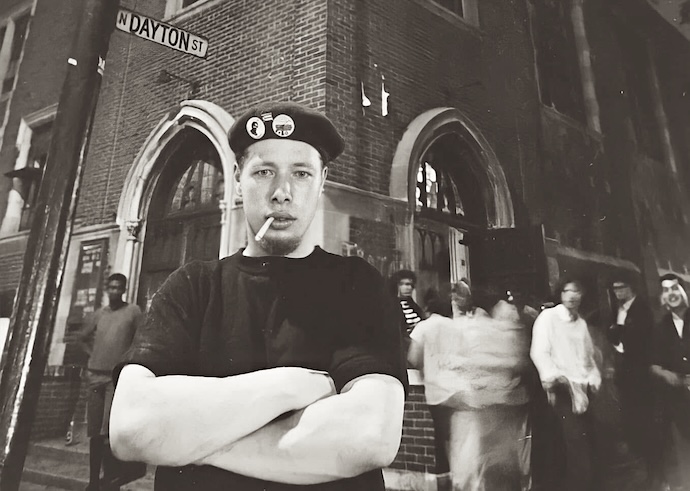

At 11 years old, Jiménez started a gang with a small group of mostly Puerto Rican and Mexican friends on the western edge of the Lincoln Park neighborhood in Chicago. They called themselves the Young Lords, and they came together to defend their community against violence and resentment from white youths directed toward Black and Brown people for moving into “their” neighborhoods in the 1950s.

The Young Lords started as a street gang committed to defending their section of the neighborhood. But late-night hangouts on the corner of Halsted and Dickens, combined with a desire to gain status and truly have something to call his own, propelled Jiménez into a life of crime. Theft and drug possession led to more than 20 arrests in the early 1960s.

In 1968, against the backdrop of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Jiménez was imprisoned again. This time, however, he was placed in solitary confinement for trying to escape. He began to reflect deeply on his life, requesting a visit from a priest and reading voraciously, delving into Thomas Merton’s The Seven Story Mountain and the Autobiography of Malcolm X.

After his release and in light of escalating conflict in Vietnam, the rise of Black Power, and urban renewal’s bulldozer taking aim at Lincoln Park, Jiménez and his comrades took action toward social justice. The new, now politicized, Young Lords emerged within a constellation of radical organizations like LADO (Latin American Defense Organization), Rising Up Angry, the Young Patriots, and the Black Panther Party. Meeting and working with other brilliant organizers like Patricia Devine-Reed, Omar and Obed Lopez, and of course Fred Hampton, chairman of the Chicago Black Panthers, contributed to the political transformation of a street gang into the Young Lords Organization (YLO).

Coalition building

With Hampton, Jiménez helped build the first Rainbow Coalition in February 1969, bringing together Black, Latino, and white activists from across the city. As an antiracist, class-based movement, they worked together to stop the destruction of urban renewal. But a mere three months later, the YLO were rocked by an off-duty police officer’s murder of Manuel Ramos, who served as the Young Lords’ minister of defense.

The tragedy strengthened the YLO’s revolutionary fire, with Jiménez later confessing to journalist Frank Browning that “Ramos’s murder was the point that I became a real revolutionary.” Just days after Ramos’ murder, the Young Lords peacefully occupied McCormick Theological Seminary (now the DePaul School of Music) for a week and renamed the Stone Academic building “the Manuel Ramos building.” The YLO’s campaign secured a pledge for almost $700,000 and institutional support toward creating low-income housing, a Puerto Rican cultural center, and a children’s center—and bolstered the Young Lords’ influence on fights about social reform and gentrification throughout Chicago.

Soon after, the YLO started working with religious leaders such as the Rev. Bruce and Genie Johnson to turn the Armitage Methodist Church into “the People’s Church,” where they opened a health clinic, day care center, food pantry and kitchen, and distributed used clothing. The move to occupy religious institutions was strategic. Most YLO members had been raised with a Christianity that emphasized justice, grace, and the responsibility to defend and protect the most vulnerable—lessons that Jiménez and the members of the YLO clearly never forgot. With protest signs that read “I was cold and alone and the Christians took my home,” they called out the hypocrisy of Christian leaders who remained silent amidst the threats of urban renewal. With a broad coalition consisting of religious leaders, radical organizations, and people from the neighborhood, the Young Lords became a beacon of hope for those who were once again being forced out of their own neighborhoods.

But in September 1969, less than a year after the murder of Manuel Ramos, hope quickly turned to despair with the brutal (and still unsolved) murders of Rev. Bruce and Genie Johnson, followed by the December murder of Chairman Fred Hampton by Chicago police. In the coming years FBI surveillance, targeted attacks on leadership, and the Nixon administration’s efforts all sought to suppress the movement, but the work and organizing never stopped. In 1975, Jiménez ran for alderman of the 46th district in Chicago. He didn’t win the race, but his move into electoral politics, and the coalitions he helped build, would lead to the election of Harold Washington in 1982, the city’s first Black mayor.

Preserving YLO’s legacy

In the years since, nothing consumed Jiménez more than historical preservation, archival collection, and a massive oral history project. The Young Lords in Lincoln Park collection at Grand Valley State University contains newspaper clippings, correspondence, FBI Surveillance documents, and other materials on the work of the Young Lords, including an oral history collection with interviews conducted by Jiménez himself. While civil rights historians have for the most part looked away—failing to grasp the enormous relevance of this movement—Jiménez once again got to work to preserve this story. My work, along with the work of scholars such as Johanna Fernández, Jacqueline Lazú, and others, has benefited greatly from the preservation work he did in the final years of his life.

I first met José “Cha Cha” Jiménez on the campus of Grand Valley State University on a cold March afternoon in 2016. He was an undergraduate student in liberal studies, and I was working through the “Young Lords in Lincoln Park” archive he helped build as part of a class assignment. As I fumbled through basic questions, trying to explain my interest in the Young Lords’ famed occupation of McCormick Seminary, Jiménez made me feel at ease with his sense of humor and his incredible memory. We talked about Lincoln Park, religion, and nicknames, including the origin of his own nickname. He said an Irish kid in the neighborhood once called him “cha-cha-cha” after the popular Cuban dance and the name stuck. With a chuckle in his voice, Jiménez let me know that he later “kicked that kid’s butt.” I left that conversation with a deeper sense of who Jiménez was: kind and generous, gracious and hopeful, a revolutionary, and an unwavering fighter with deep pride in and love for his Puerto Rican and Mexican community.

For Jiménez, and the coalition of activists that fought alongside him, the struggle for freedom included a range of intersecting issues, from police brutality to housing displacement to economic discrimination. But more than that, Jiménez believed in the power of coalition building. He believed deeply in interdependence, in the idea that movements must form broad coalitions, and that communities as far away as Lincoln Park and Puerto Rico share a desire to be free. Jiménez and the Young Lords aren’t simply a historical footnote in a regional narrative about injustice, they’re a national phenomenon that laid the groundwork for Latino radical movements across the country. José “Cha Cha” Jiménez, ¡Presente!