What inspired you to write God’s Heart Has No Borders? What sparked your interest?

Back in 1986 I was working in a largely Mexican immigrant community in the San Francisco Bay Area. A new law had just been passed (the Immigration Reform and Control Act, or IRCA) and it divided undocumented immigrants into two groups: those who could legalize and get on that promised pathway to US citizenship, and those who would be criminalized and forced into the shadows through employer sanctions.

People were distraught and fearful. Many families wondered if they would be torn apart between nations, with some members deported and others getting green cards. Community coalitions quickly mobilized to deal with these new realities, and I witnessed how many of these efforts were organized by faith-based organization, and took place at local parish sites. I realized then that religion had tremendous power to be a force for positive change in immigrant America. That was my first big “aha” moment, and that’s when I decided that I wanted to find out how religion plays an important role in these processes.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

That’s a tough question! But it’s fair enough. I have a few take-home messages.

First, immigrants are not the problem. The way we welcome immigrants to the nation—or fail to do so—is the problem. Welcoming and integrating new immigrants has caused much strife in our country in recent years, and I want readers to know that religion has the potential to lessen human conflict, suffering and exclusions. In fact, religious people have already been actively working to include immigrants in US society. This occurs in many ways, as I explain in the book. I show how Christian, Muslim and Jewish people rely on religious faith and resources to help re-think moral guidelines and implement what is just and fair for new immigrants. Can we exclude, deport or incarcerate people because of skin color? On the basis of religious beliefs? For being poor? Religion gives people moral guidelines and the opportunity to reflect, and upon reflection, most religious people answer no to these questions. Some of them go further and put their morality into action. They become agents of progressive social change, and that is a story of hope.

And finally, I don’t pretend to cover all religious activists who are working for immigrant rights and inclusion here. But I do cover a diversity of religious activists and immigrant rights issues in this book. I focus closely on three cases: Muslim American immigrants working to defend their civil rights and civil liberties after 9/11; Jewish and Christian clergy advocating for the rights of Latino immigrant service workers and unions; and Christians of various denominations and racial-ethnic backgrounds working together for justice at the US-Mexico border, where so many people are dying each week. And there is quite a bit of interfaith mobilization and cooperation. There are multiple sites, and many different ways in which religion is brought to bear on these important issues of immigrant justice and inclusion.

Anything you had to leave out?

Yes, lots. Over the years, and with the help of USC students, I collected more information than I could handle in the book, given the page limitations. For example, I gathered interviews with many priests and religious leaders who participated in the Immigrant Workers Freedom Ride, but none of that material appears in the book. I also followed and participated in some of the activities of two other religious groups working for immigrant rights and integration. I took lots of field notes and collected flyers and documents on these. I attended many evening and weekend meetings, took buses to Sacramento with religious people who were calling on their representatives for reform, and I followed a faith-based group working on low-income housing access for new immigrants, but in the end, this was just too much to include.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

There are a few big ones. First, because of the way the media sensationalizes “religious people behaving badly” (pedophile priests, philandering evangelicals, or the intolerance of Christian and Muslim fundamentalists), many people in the United States remain unaware of the progressive potential of organized religion.

Second, many people see immigration in “them” vs. “us” terms, and in fact, our fates and destinies are intertwined. Many religious people get that, and integrate that understanding into their actions.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

This is a book for all Americans. It’s written for everyone who wants to find a way beyond the stalemate of immigration politics. I hope that religious people and secular people, academics, students, and engaged citizens will read it.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Give them pleasure? Piss them off?

I want the book to inform people, and I hope people will find a few surprises too. I think there are many untold stories here, stories of the ways religious people are quietly and steadfastly working towards these goals of immigrant rights, inclusion and integration. These stories and people deserve to be known. I hope the book will be pleasurable to read, but also challenging, as it makes several analytic observations about the complicated ways in which religious belief, ritual, resources and scripture are used—and sometimes cannot be used—in these movements for social change. Those discussions should interest academic audiences who specialize in studying social movements and religion. I’m not trying to piss people off, but invariably, some people will be angry.

What alternate title would you give the book?

Well, I had initially wanted to call it “Faith in Immigrant Rights” but my editor wisely counseled me away from it. Instead, I went with one of the quotes from an interview.

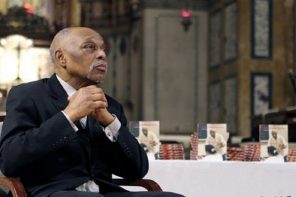

How do you feel about the cover?

I didn’t have much of a hand in it. My father was dying as this book went to press, and it was tough year for me. There might be a little too much text on the cover, but I am very grateful to my editor, Naomi Schneider for finding the photo and securing the rights to reproduce it. As she observed, my life was held together with scotch tape at that time, so any cover is a good cover. The inside counts more, right?

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

Many!

What’s your next book?

I’m embarking on something quite different. It will be a sociology of gardens. My working premise is this: Gardens invoke Eden, but they are not innocent. In fact, they are grounded in society, so they reflect prevailing social cultures of power and culture.

Visit our RDBook page for a complete list of our interviews with authors…