Anderson Cooper’s journey into mindfulness was featured on the latest episode of 60 Minutes, and it proved to be a textbook example of what I call the mystification, medicalization, mainstreaming, and marketing of mindfulness. That’s good for me—analyzing these sorts of programs is my bread-and-butter as a researcher—but it’s too bad that the venerable program didn’t try to investigate any deeper.

Watching 60 Minutes, the viewer would have virtually no opportunity to realize where this mindfulness comes from—the piece treats it as having essentially sprung from Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn’s well-functioning brain.

In fact, mindfulness is a Buddhist meditation practice, and it was from Buddhists during Buddhist meditation retreats that Kabat-Zinn learned about mindfulness in the first place. If you know what to look for, there’s lots of Buddhism on display during Cooper’s report, but none of it is ever attended to, and the average American probably can’t decipher what’s being shown.

So we see Buddhist meditation practices (mindfulness, called sati in the Buddhist Pali language), Buddhist meditation postures and gestures (Kabat-Zinn holds his hands in a mudra position), Buddhist meditation cushions (zafus and zabutons, imported via Japanese Zen Buddhism), Tibetan Buddhist hand cymbals, and actual Buddhists (Chade-Meng Tan, among others) on-screen, yet they are never decoded so that we can understand them. Buddhism is never referenced at any point, except for a brief allusion to “the Zen people from ancient China” as folks who knew better than us. This is an example of what I call mystification: the obscuration of mindfulness’s roots and usual context so that it can be extracted from religion and recontextualized to fit new purposes.

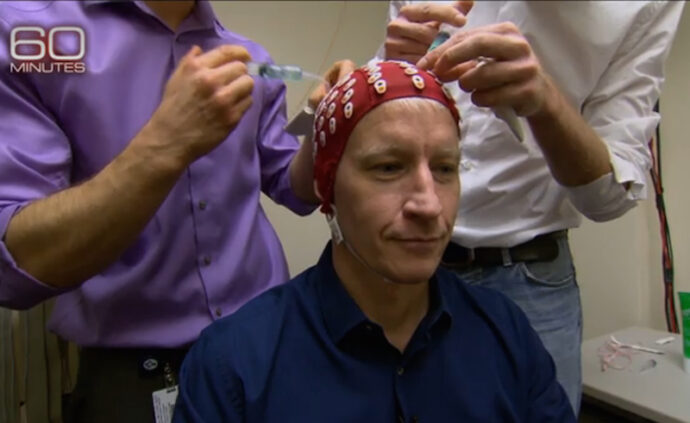

Instead of religion, the context for mindfulness on 60 Minutes is medical science. We’re shown headlines from journal publications that claim to measure health benefits from mindfulness practice, and Anderson Cooper gets himself fitted with a brain machine so we can watch him stress out and then calm down with mindfulness. Cooper throws a softball question to Kabat-Zinn, inviting him to explain to us why this mindfulness stuff isn’t “New Age gobbledygook,” which provides a further opportunity to reinforce that this is all perfectly natural activity approved by doctors and scientists.

Of course, this sort of medicalization can only take place after the religious context of mindfulness has been hidden from attention, if not from view. Assuring the public that mindfulness is a form of medicine (and therefore secular, in the contemporary American context) is important. There’s a lot at stake here that could be held up if too many questions about religion were asked. For instance, we learn that Congressman Tim Ryan (himself a Roman Catholic, not a Buddhist, though the program doesn’t ask about his religious background either) has secured $1 million dollars from the federal government to bring mindfulness into Ohio schools in his district. If he asked for that money to teach the rosary to public school kids, would that really fly? Better to follow the lead of UMass researcher Judson Brewer, who tells Cooper that mindfulness is “just the next generation of exercise.”

The mainstreaming of mindfulness is the real crux of the piece. Rather than using mindfulness to purify the mind as part of a celibate monastic exercise designed to sever the karmic cycle of rebirth and bring about nirvana (the original purpose of mindfulness), mindfulness is here applied to mundane worldly concerns, for achieving practical benefits that Americans feel they need. The piece begins by talking about how stressed out everyone is, and throughout Cooper’s journey we’re told that mindfulness will help us calm down and live in the moment. Kabat-Zinn tells us that mindfulness is useful for “anxiety, depression, stress reduction,” and similar ills of an over-worked age.

Applying mindfulness to problems and anxieties that mainstream Americans already have allows it to make the jump from marginal monastic concern to pop phenomenon. This isn’t how it was used in Asian tradition, but new societies and demographics naturally call forth new applications; those traditions that either aren’t flexible enough or are somehow unavailable for selective appropriation by new promoters and practitioners won’t successfully make the jump into previously untapped cultures.

One more essential process is required for a practice to succeed in 21st century capitalist America: it needs to be commodified for the marketplace. Mindfulness comes to us packaged with Colorado retreats for high-powered professionals, training sessions at Google (which gets lots of free good press), and all sorts of paraphernalia. We’re told about the various books that interviewees have written (ten, in Kabat-Zinn’s case), how Chade-Meng literally makes his living promoting mindfulness in Silicon Valley, and you can learn more about Cooper’s experiences by visiting an online extension of the report sponsored by Pfizer, the makers of Viagra. There’s a lot of money to be made off of the American consumer’s exhaustion, but the economics of the mindfulness juggernaut are left unexamined by Cooper.

The 60 Minutes piece, basically a commercial for the allegedly de-Buddhified arm of the mindfulness movement, couldn’t be any more positive if it were paid for by Kabat-Zinn himself. That’s pretty common, but it’s still unfortunate. Mindfulness may deliver some of the benefits that promoters tout, but Americans deserve to be informed about the full context of what they’re being sold. There are studies that suggest mindfulness can have a serious adverse effect on some practitioners, and much of the research has been criticized as sloppy, methodologically-unsound, or as failing to show actual results from mindfulness.

Cooper shows us the Wisdom 2.0 Conference, but doesn’t tell us that it’s actually the target of serious dissension within the mindfulness movement itself, with Buddhist protesters carrying out Occupy-type activism against it as an example of classist degradation of the practice. And above all, the religious connections and background of mindfulness—which might provide food for thought for Christians, atheists, and other possible viewers, if they were given the chance to contemplate such connections—are left aside.

Maybe the benefits outweigh the risks; maybe the race and class issues on display in wings of the mindfulness movement can be overcome; maybe mindfulness can be effectively shorn of its religious genesis; maybe mindfulness really will save us from ourselves. And it’s quite possible that viewers might reach those conclusions. But they’ll never have the chance when presented with fluff pieces that fail to include even an iota of journalistic skepticism.