Since the rise of the corporation in the 19th century, Christian businessmen have treated the American marketplace as a religious site—and a means to promote evangelical Christianity and its politics.

Controversies surrounding Chick-fil-A, Hobby Lobby, and bakers who refuse to make wedding cakes for same-sex couples are just the latest in a series of public skirmishes between self-described Christian entrepreneurs and the laws and regulations that govern American business.

Indeed, as historian Darren Grem relates in a compelling new study, when evangelicals found the public square increasingly hostile to religious influence, they turned to corporations to enact and advance their conservative values.

The Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity

Darren E. Grem

Oxford, 2016

Grem’s new book, The Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity, examines how Christian businessmen imbued American corporations with religious meaning and how free-enterprise ideology and market-based solutions in turn shaped 20th-century evangelical institutions.

RD’s Neil J. Young recently spoke with Grem about the book.

_________

As you point out, we have a robust history of how conservative evangelicals shaped American politics in the 20th century, but the history of evangelicals and corporate capitalism has been less examined. How did this relationship emerge? And what do we gain by looking at how evangelical Christianity became friendly to business and took on the culture of corporate capitalism?

Large-scale corporations became prominent institutions in American life soon after the Civil War. Not to say that corporations or business ventures of various sizes and types weren’t there before, of course, but in the late 19th century they begin to have sustained social and political importance and, I argue, become a religious and cultural tool for evangelicals.

Evangelicals at this time were wrestling with all the dramatic changes to private and public life that corporate capitalism and modernity introduced. I focus on those evangelicals who were more comfortable with the corporate men and means than were not.

In doing so, we find a story of modern evangelicalism that other scholars have mentioned in passing but have not made central to their understanding of how conservative evangelicals navigated their way into the 20th century. We uncover a business history of one of the nation’s most politically important and culturally significant movements, a kind of top-down history that complements and revises the other “preacher-leader driven” histories we have.

We also have to wrestle with what evangelicalism actually was and remains, which is a religious identity shaped by money, marketing, corporate power, corporate executives, and private-sector places and spaces.

Indeed, places and people typically deemed “secular” or “non-evangelical” were also the means by which the evangelical sense of “the religious” was made. Detailing evangelical activities in the business world reveals the porous boundaries around a modern faith that—especially in journalistic treatments—typically appears as anti-modern or reactionary. Resistance to change is a part of the story, to be sure. But when taking account of its friendliness toward business, conservative evangelicalism emerges as a proactive, pragmatic faith.

Its practitioners were savvy and strategic, welcoming a variety of ideas from what they certainly saw as “outside” their world (from reformist progressivism to positive thinking to ecumenical pluralism) when constructing their visions for what it meant to live, think and work in a nation of corporations.

This insight should help to contextualize the present with the past, especially in this election year. White conservative evangelical fandom for a tycoon and top-down authoritarian such as Donald Trump is hardly out of step with how previous born-again Americans wooed business elites who seemed the best champions for their social, economic and political aspirations.

It struck me how so many of the actors in your book—from the shoe manufacturing tycoon W. Maxey Jarman to the motivational writer and speaker Zig Ziglar—saw the Bible as a plain-truth guide to business. How did these Christian businessmen understand their evangelical faith and fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible as not merely divine support for capitalism and free enterprise ideology, but as a clear and specific guide to business practices? And does this change over time?

The businessmen I studied were not biblical sophisticates. As you note, they generally held to a kind of “plain reading of the text” approach, which was paradoxical in that it often served as the foundation for their figurative interpretations regarding the economy. Their readings were also highly selective. Certain passages regarding poverty and wealth were played up, played down, or reinterpreted as biblical support for “reaping what you sow” through work and personal accountability.

Nothing about this was new in the 20th century. But it did have a certain saliency and overlap with evangelical anti-New Dealism, anti-communism, colonialism and activism. The variety of approaches to the Bible is what I want readers to consider. There was some agreement between businessmen regarding the Bibles that sat on their desks. For the most part, they were interpretive pragmatists, using various passages and parables to support a host of economic and political positions that they wanted to market as “evangelical” or “conservative” or even more generally as “Christian.”

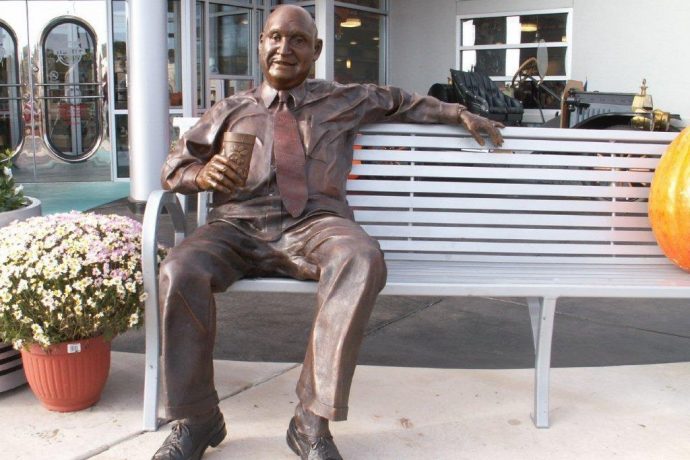

When business leaders like Chick-fil-A’s Samuel Truett Cathy or evangelical writer Zig Ziglar speak of their politics or business philosophies as “based” in the Bible, I detail what that statement and interpretive behavior entails. In one of my favorite moments of self-admission, Ziglar referred to his take on the story of David and Goliath—which he interpreted as supporting pull-your-bootstraps-up striving and meritocratic work—as “slightly Ziglarized.” That he was applying a personalized reading of a text gets at the dynamic, multi-faceted relationship between business leaders and the “good book” that they saw as the primary source for doing “good business.”

How did the business world become an arena for evangelical politics after Supreme Court rulings and federal legislation largely removed religion from public schools and other public spaces? And how did evangelical businessmen (this story concerns white men almost entirely) become some of the most effective activists not only for free-market economic policy but also for conservative causes that we think of as “culture war” issues, particularly matters of gender and sexuality?

The business world was an arena for evangelical expression for most of the 20th century. But with the postwar federal state challenging the evangelical establishment at work in businesses, the evangelical-friendly business took on new meanings and purposes. Increasingly after the 1960s, the small and large business became yet another place outside their churches, colleges or local communities where evangelicals could express their religious, social and political views. They did so with fervor and aplomb while linking such views to the profit motive.

On this point, I want readers to think about the extent of business-based evangelical activism and how religious expression and politics work in a market-based environment like a business. Instead of thinking of religious activism in terms of sheer votes or legislative wins, I emphasize that we should think about it as a kind of cultural power that historians haven’t often considered. That cultural power exuded certain “Christian” characteristics in advertising, in-house activities, philanthropic interests and so on.

A few executives organized their businesses around conservative “culture war” issues and linked them to personal views regarding work, wealth, poverty, the state and the economy. Others developed a profitable set of cultural industries—in music, publishing and other media—that provided evangelical consumers a market-based means to express their social politics and public-sphere identities as “Christians.”

As a result of such efforts, by the 1980s, when one thought of “Christian” or “Christian politics” or “Christian business,” a liberal Protestant or African-American did not come immediately to mind. Interestingly, the recent Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, from Rev. Dr. William Barber’s speech to Hillary Clinton’s keynote address, reframed such linkages, referencing a religious and political linkage that conservative evangelicals in business have tried to keep out of the nation’s discourse.

Readers may think they are familiar with the story of Chick-fil-A and its founder, S. Truett Cathy, but you use this well-known fast-food chain to explore the racial politics at work in the development of American business in the twentieth century. Indeed, race and racial politics emerge as a perhaps unexpected theme of your book.

I’m glad you picked up on that. I recently had a conversation with a colleague about certain conversations that are opening up in evangelical quarters about race, racism, white privilege, and so on. “Reconciliation” efforts in various conservative denominations, from the Southern Baptist Convention to the Presbyterian Church in America, are a good first step toward reckoning with the dilemma of race. The problem is the very problem that Chick-fil-A and other businesses represent. They cannot be distanced from questions of economic inequality and the American business.

To be sure, many evangelical businesses shoot for racial diversity or promote “color blind” office policies. That is a stark departure from the openly discriminatory practices of the past. But race is also downplayed as a determiner or dynamic in one’s life while work or, rather, attachment to a faith in the free market and the American Dream of meritocratic uplift, is made front and center.

Such a religiously-infused politics regarding the economy is and was almost universally promoted by white evangelicals looking for a new way to make sense of a nation where legal segregation was out but its legacies remained alive and well in thousands of different ways.

For white evangelicals, efforts to address the nation’s troubled racial history usually start and stop at questions of racial inclusion or sensitivity, primarily in the private spaces of churches or denominational organizations. My book suggests that they should extend to questions of business access, jobs, wages, and a host of other issues because white evangelicals have long been involved in such issues themselves, albeit largely for the purpose of securing white privilege and white-made terms of what it means to be included and of value in the nation’s social and corporate landscape.

You close your book by commenting on the emergence of “religious freedom” language as not simply the latest political strategy of religious conservatives, as many historians have argued, but rather as a discourse and logic deeply rooted in the longer history of evangelical enterprisers and “Christian” businesses your book documents. How do ideas about religious freedom come from a particular evangelical view of business and what do you imagine this will look like in the coming years?

Contemporary conservative evangelicals often cast the “religious freedom” question as an exercise in constitutionally-guaranteed, First Amendment discretion. That’s not a far stretch from the same arguments used by segregationists arguing for the “religious freedom” to set up all-white segregation academies in the 1970s or defend a white-led Cold War for “religious freedom” and capitalism against Cold War communism.

But discretion plus privilege is discrimination. And evangelicals have enjoyed a longstanding right to define the terms of “religious freedom” as it benefits their own cultural position, a position that has been faltering for the better part of a century. In the coming years, it’s an open question regarding how much the courts buy their appeals to operate businesses as “religious” places deserving of certain legal protections.

That they are appealing to a secular idea, namely religious freedom, is instructive and interesting but not out of step with their forebears, especially those in business. A business history of conservative evangelicalism shows that evangelicals have long treated spiritual and religious freedom (and its attendant economic, social, and political affects) as intertwined with the fate of business enterprise and business decisions.

Decades ago, however, evangelicals did not need a court to secure what they deemed the “rights” of the faithful in business. Today, then, seeking a court, an institution really of the state, to preserve or promote such “freedoms” may be a last resort of conservative evangelicals. And I doubt that, in a dramatically changing and diversifying country, it will bring in substantial political or social rewards. But it may help evangelicals to retain what they have won over the better part of a century and still seek in thousands of small businesses and myriad business activities, which is a certain resilient place in and through private-sector America.