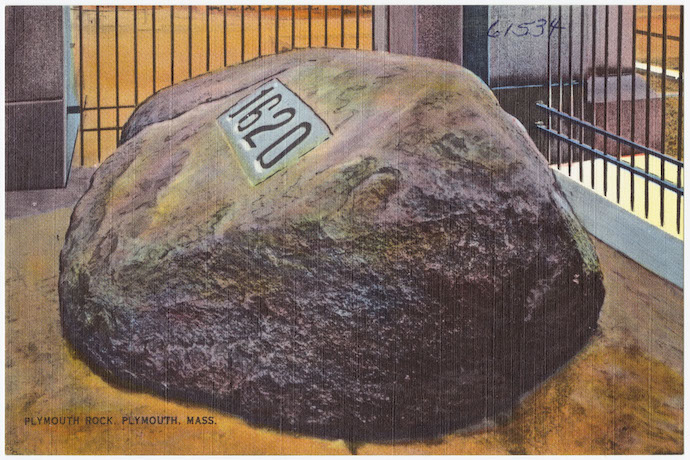

Within William Bradford’s massive work, Of Plymouth Plantation, composed between 1630 and 1651 while he was occasional governor of the colony, there’s no mention of the eponymous rock upon which the pilgrims supposedly landed when they reached their permanent home in Massachusetts. Not a single page of Bradford’s contemporary account gives description of the hefty, jagged, grey boulder sitting on the rocky beach of Plymouth Harbor, or of the pilgrims’ landing upon it on December 18th, four hundred years ago this week.

The earliest mention of what would be called “Plymouth Rock” as the landing spot of the pilgrims isn’t until 1741, when an elderly resident of the town claimed that he’d been told in his youth that this exact stone was the landing spot for the Mayflower. Even discounting the physical impracticality of the elderly gentleman’s specific claim, his assertion some twelve decades after the Mayflower’s arrival, with absolutely no historical corroboration, would seem to justify significant skepticism regarding the legend.

And yet the French author Alexis de Tocqueville would write in his 1835 Democracy in America that the “Rock is become an object of veneration in the United States… it is treasured by a great nation, its very dust is shared as a relic.” Americans possessed shards of the rock as souvenirs and sold them as commodities, but as historian John G. Turner quips, “Just as some American chipped away at Plymouth Rock, so others have chiseled away at the mythology surrounding the Pilgrims.”

In the grand scheme of historical memory, a misidentified rock is a relatively paltry issue, but it’s instructive in the way in which facts and their variable interpretations can be used in the invention of national myth. Appropriate then that this bit of national kitsch is perhaps an exemplary representative of public historical memory precisely because it’s an artifact of fiction rather than of reality.

Still, in the afterglow of Thanksgiving, and now on the quadricentennial of the pilgrims’ arrival, it’s crucial to rethink the United States’ relationship to some of its founding myths, especially in our current season of national soul searching (which has been unequally embraced by some critics). All the more crucial because what generations of American schoolchildren are taught regarding the arrival of English separatists to a country already inhabited by Abenaki, Wampanoag, and Pequot (among others) is in almost all of its interpretive particulars incorrect.

As concerns the pilgrims, that national myth is composed of hagiographical accounts which are mainstays in both the educational system and the broader culture. That perspective describes the arrival of the pilgrims as a straightforward victory for religious liberty, and the progenitor for what would become American democracy. Far more complicated is the reality, whereby the arrival of the colonists ultimately resulted in the ethnic cleansing of New England’s native peoples, while also exacerbating the most virulent pandemic in history. Any decent respect for the truth can’t possibly whole-heartedly embrace the myth while ignoring the facts.

Virtually all of the Thanksgiving accoutrement that we gild the pilgrim narrative with is wrong, and no serious scholar entertains the most potted and simplistic version of the story. The claim that the Mayflower uncomplicatedly led towards American democracy, even while the Compact which organized their mission is justly celebrated for its nascent egalitarianism, is to read the past backwards in light of the future. Perseveration on English settlers ignores the equally important, or often more important, role of Spanish, French, and Dutch (among others) colonial projects in much of what would become the United States—not to mention the presence of native peoples and enslaved Africans who contributed to the development of American culture.

Most laughable of misapprehensions about the pilgrims is the sentimental pablum which reads the theocratic Calvinists as uncomplicated partisans of ecumenical religious liberty. Historian Abram C. Van Engen explains that the language of liberty associated with the pilgrims and puritans, “especially in a religious context, had little to do with the idea of freedom that many people have since embraced.” The concerns of that first generation have far more to do with social control and church governance than they do with social libertarianism or some kind of all-American mantra of uncomplicated freedom.

And while the “first Thanksgiving” held a year after the Mayflower’s arrival is, in its own way, a powerful and poignant symbol about the possibility of reconciliation, tolerance, and gratitude, it also belies the realities of subsequent violent conflicts like the Pequod War and King Philip’s War. None of this impugns the personal bravery or hardship of individual pilgrims and puritans, nor is it to not admit that much was sophisticated, ingenious, and complex in their theology and literature. But it is to say that if we’re to memorialize history and not an illusion, we must be cutting and honest with the full record, and justly consider how we memorialize the past and craft the narratives we tell about our origins.

This past year has been a season of demolishing historical idols (sometimes literally), though it hasn’t been universally welcomed. As Black Lives Matter protests initiated a crucial reckoning about who, what, and how we memorialize history, there’s been a reaction to that long overdue conversation that has doubled-down on historical fallacies and misinterpretations. In response to BLM, armed protestors marauded in front of Confederate memorials and statues honoring Christopher Columbus, while the now outgoing Trump administration proposed something called the “1776 Project,” with the quasi-authoritarian goal of what they call “Patriotic Education.”

This initiative was consciously molded in response to The New York Times’ “1619 Project,” which interpreted American history in light of the arrival of the first slaves at Jamestown (a year before the Mayflower landed in Massachusetts), and which has received criticism from conservative politicians and pundits, despite its scholarly bona fides. As a representative example of this perspective, Arkansas senator Tom Cotton has denounced those who called the conventional narrative about the pilgrims a “myth and a caricature,” and yet all of Cotton’s fury and mockery doesn’t change the fact that the conventional Mayflower narrative is a myth and a caricature. By the standard of historical interpretations needing to match reality, the traditional Mayflower myth as valorized by Cotton on the floor of the Senate falls far short of the truth.

Speaking in a more intellectual idiom than either Cotton or Trump, literary scholar Alan Jacobs criticizes more complete historical accounts in an interview with The Point as having “deliberately re-narrated” the past, and yet that’s precisely what all scholarship’s purpose is, with the faith that ever more nuanced and subtle interpretations of the record will help us approach some understanding of the truth. Those who are not trained in historiography more generally, or seventeenth-century American history more specifically, may be surprised to learn that much of the conventional narrative about Plymouth is either embellishment, imagination, obfuscation, or willful denial, which is why it’s the duty of scholars to question or correct those myths when the circumstances compel us.

There’s a difference between understanding historical scholarship as an ever-contingent and evolving set of interpretations versus seeing it as a reservoir of static symbols on behalf of the status quo. To speak the truth with finesse and complexity isn’t to deliberately re-narrate the past, it’s to finally utter truths that have long been obscured under sentimental nostalgia. Furthermore, it’s to understand that history is never settled, that there is no originalism by fiat when it comes to the drafts of the past. Perhaps Americans would be better served by being instructed not just in history, but in historiography, that critical method and practice which understands that the past is a variable thing, open to a multitude of interpretations.

Conservative partisans may see revisionism as something unpatriotic, but historian John Burrow reminds us that such work is a “part of Western culture as a whole—at times a highly influential and even central part,” where there has always been an awareness of the fluctuations in the stories we tell. History is frequently configured as being as solid as a rock, but historiography reminds us that it’s perhaps more like the ocean which brought the Mayflower to Massachusetts—sometimes stormy, sometimes clear, and always variable—but still capable of delivering people from one shore to another. Such a perspective isn’t a rejection of the truth, it’s an invitation to a more complete, subtle, nuanced, and detailed truth, so that we need not embrace myths of the past to understand where we’ve been.