Over the past four decades, a small group of Catholic activists has worked to symbolically disarm nuclear weapons. These activists have made headlines—and, in many cases, served prison sentences.

Plowshares activism was launched in 1980 by Daniel and Philip Berrigan, the duo of brother-priests previously known for their opposition to the Vietnam War. A select group of radical clergy and dedicated laypeople, the Plowshares have challenged the national security apparatus wielding little more than wire-cutters, hammers, prayers, and bottles of their own blood.

Plowshares: Protest, Performance, and Religious Identity in the Nuclear Age

Kristen Tobey

Penn State University Press, July 2016

In Plowshares: Protest, Performance, and Religious Identity in the Nuclear Age, Kristen Tobey examines the methods of Plowshares activists, and she dives into their devout, dramatic, and often perplexing work.

Tobey is Visiting Assistant Professor of Theology and Religious Studies at John Carroll University. RD’s Eric C. Miller spoke with her about her project.

____________

Eric Miller: What is Plowshares activism, exactly?

Kristen Tobey: Plowshares activism is a strand of high-risk Catholic antinuclear activism consisting of civil disobedience actions (Plowshares activists prefer the term “divine obedience”). Participants trespass onto sites where nuclear equipment is manufactured or stored—such as the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where a high-profile Plowshares action was carried out in 2012—in order to “symbolically disarm” the equipment.

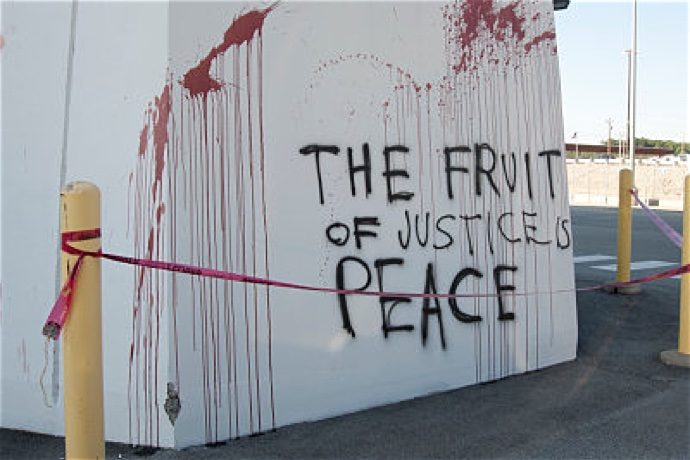

Typically in a Plowshares action, symbolic disarmament involves pouring blood—the activists’ own—over the equipment and hammering on it with household hammers, in a nod to the Hebrew prophet Isaiah’s image of beating swords into plowshares (Isaiah 2:4) from which these activists take their inspiration and their name.

The first Plowshares action was conceived by Philip Berrigan and others as a way to continue the momentum of the Vietnam-era Catholic Left, but in a way that would be more truly faithful, riskier, and hence more efficacious. Actions are still taking place today, though far less frequently than in earlier decades.

Plowshares activists in the United States have never been acquitted of the charges brought against them, which include conspiracy, sabotage, and destruction of government property. They have received prison sentences of up to eighteen years. Because these actions carry such a high risk of legal consequences and bodily harm—many take place in deadly force areas—many in the larger Catholic Left regard Plowshares actions as virtuosic: Catholic resistance par excellence, so demanding that it is admired more than it is emulated.

You note that trespassing, blood, and hammers are the hallmarks of Plowshares activism. But there must be more innovative options available. Why stick to these three?

That’s a polite way of putting it. The critique that what they do is ineffective and irrelevant—not only that their tactics are unproductive but that the nuclear issue is no longer a pressing one—comes at Plowshares activists from all directions—even, sometimes, from people who support the idea of religious resistance.

But in the Plowshares’ worldview, faithfulness to a Biblical ideal of nonviolent witness is the orienting value. Plowshares activists approach nuclear weapons as both a symbolic and a real threat, and they employ trespass, blood, and hammers as both symbolic and real means to disarm them.

On the one hand, Plowshares actions are willfully symbolic because nonviolence depends on it. On the other hand, activists do want to disable the equipment in a “real” way. They want to be destructive, but, as I discuss in the book, there are theological and social risks bound up with being too destructive, and there are no clear demarcations telling activists how much is too much.

If the first half of a Plowshares action takes place in the field, violating (certain) laws and getting arrested, the second half plays out at trial—kind of like an episode of Law and Order. In what ways does the courtroom drama supplement the performance of symbolic disarmament?

Their time in the courtroom is crucial to the Plowshares’ project. The first Plowshares activists recognized the value of the legal sphere for spreading their message and refused an offer to have all the charges against them dropped (including several serious charges that carried heavy penalties) upon the condition that they refrain from civil disobedience for the next six months.

Today, in the majority of Plowshares actions, participants are not immediately apprehended at their action sites and could easily turn around and walk out the same way they came in. They never do, sometimes waiting hours for their presence to be noticed.

Facing consequences is an important component of much nonviolent activism, and it takes on an extra resonance for activists who model themselves after Jesus and other historical and Biblical martyrs.

The courtroom provides an arena for Plowshares activists to decry nuclear weapons. Plowshares activists are there precisely to talk about what they’ve done. But the courtroom is also a highly regulated space. Almost always, the rules of the courtroom prevent Plowshares defendants from speaking freely about nuclear weapons and about their motivations.

As much as they are an immediate hindrance, though, the limits placed on Plowshares defendants enable them to present an alternate conception of justice than the one the courts represent. They regularly defy the courtroom’s conventions (and their judges’ direct orders) by turning their backs on their judges, refusing to participate further in their trials, and so on. Sometimes they flout convention in more subtle ways. Whether direct or indirect, these instances of rule-breaking all function as performances of identity for the activists, through which they instantiate the roles of prophet and martyr.

Thanks in large part to the activists’ own legal savvy, the courtroom itself becomes a religiously fruitful space even though, contrary to what one might reasonably expect, Plowshares trials often proceed without much explicitly religious content at all.

How so?

It varies. Sometimes religious content is explicitly disallowed by their judges, if it is deemed to fall outside the courtroom’s discursive parameters. (Defendants don’t always comply with their judges’ orders on this, leading to some of the instances of rule-breaking I mentioned.) Other times, defendants themselves choose to limit the religious content of their testimonies.

Notably, in almost every Plowshares case to date, defendants have opted not to use a religious freedom defense, even though they understand their actions, and even their time in court, to be deeply religious. Instead, they’ve used the principles of necessity and international law to ground their defenses. I argue that they choose these latter defenses not because they are more successful—they aren’t—but because they are less particularizing.

The relationship between religious groups and the courts in the U.S. often gets circumscribed within a sequence of First Amendment cases in which a certain power dynamic prevails: religious actors present their practices to be judged by authoritative courtroom agents who, in deeming those practices legal or not legal, powerfully shape the religious worlds that those actors inhabit.

The Plowshares’ trials show a different dynamic at work, in which religious actors are themselves agents in the processes of religious production taking place in the courtroom.

Plowshares activists are a small group, comprised of aging activists. The Berrigan brothers have passed away. And yet, as Eric Schlosser documents, the American nuclear arsenal remains large, powerful, and not entirely secure. Looking back, how do the remaining Plowshares activists evaluate their legacy? Do they have a future?

Plowshares activists certainly are interested in growing the peacemaking ranks in general, but recruiting new activists for their very particular type of action is not something with which they much concern themselves. Early in their history, Plowshares activists realized that the nature of their actions would limit participation, and they decided that maintaining the drama and efficacy of the actions was more important than increasing the number of participants. They use the language of vocation to talk about their project, not the language of social movements.

Of course the corollary is that as the years go by, there are fewer Plowshares activists and fewer Plowshares actions. But their worldview has always accommodated small numbers, characterizing them as a mark of faithfulness and authenticity. Faithful witness is a legacy that Plowshares activists are proud to claim, even if the nuclear threat hasn’t been eradicated.

That’s not to say that Plowshares participants haven’t hoped for, and worked toward, instrumental outcomes. I am sure they were moderately pleased when the Oak Ridge Y-12 facility shut down for two weeks after the 2012 action. We know that the national nuclear arsenal is not as secure as we would like to believe at least in part because of Plowshares activists. I have no doubt they recognize that as an achievement.

But there is far more to success for the Plowshares than the instrumental outcomes that may or may not result from their actions. Several years ago a Plowshares stalwart wrote to me, as she awaited trial, that she was grateful for the chance to shed light in the darkness. She wrote of her hope that “continuing to be faithful enhances the world in the future.”

For the Plowshares, the truest success lies there, at the nexus of faithfulness and hope, of the right now and the yet to come, where activists locate the significance of their actions both for themselves and for the world.

So, it is neither unreasonable nor overly cynical to conclude from the demographic data that Plowshares activism, at least as it has been carried out for the last three and a half decades, probably does not have much of a future. But that isn’t the whole story, or even the most important chapter. What matters to the Plowshares is that in the present they are doing what God calls them to do, and in the process becoming who God expects them to be.

* * *

Also on The Cubit: Prisoners in the hands of an angry God

Follow The Cubit, RD’s religion-and-science portal, @TheCubit