Prince is dead. Long live Prince.

The morning after Prince’s death was announced, I woke up, remembered he was dead, and buried myself under my duvet. I’m still in shock. How could that beautiful, complicated body be gone?

Prince, the demi-god of sexuality, lust, and yearning, seemed immortal. Watching him perform was like seeing a fusion of Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Marvin Gaye, and a black preacher with an anointing. Prince’s body was fused to his guitar, and his dancing was the uninhibited dance of possession—not by an evil spirit, but the spark of divinity. His moans, arcs, and cries in songs like “Darling Nikki” and “When Doves Cry” cut deep. His lyrics, even the most libidinous ones, pointed to a union of desire and the divine. No other artist tapped into spiritual truth and multiple orgasms at the same time the way Prince did. He didn’t even have to say the words—his moans said everything.

Listening to Prince made you all hot, bothered, and anxious. Especially anxious.

That anxiety wasn’t only about lust, but about the intensity and romance of many of Prince’s lyrics. Prince seemed to be looking for that perfect sexual partner who could make him say god and feel God. Sex for Prince was rapture. But many adults were scared of what Prince was waking up in their children—my own mother included.

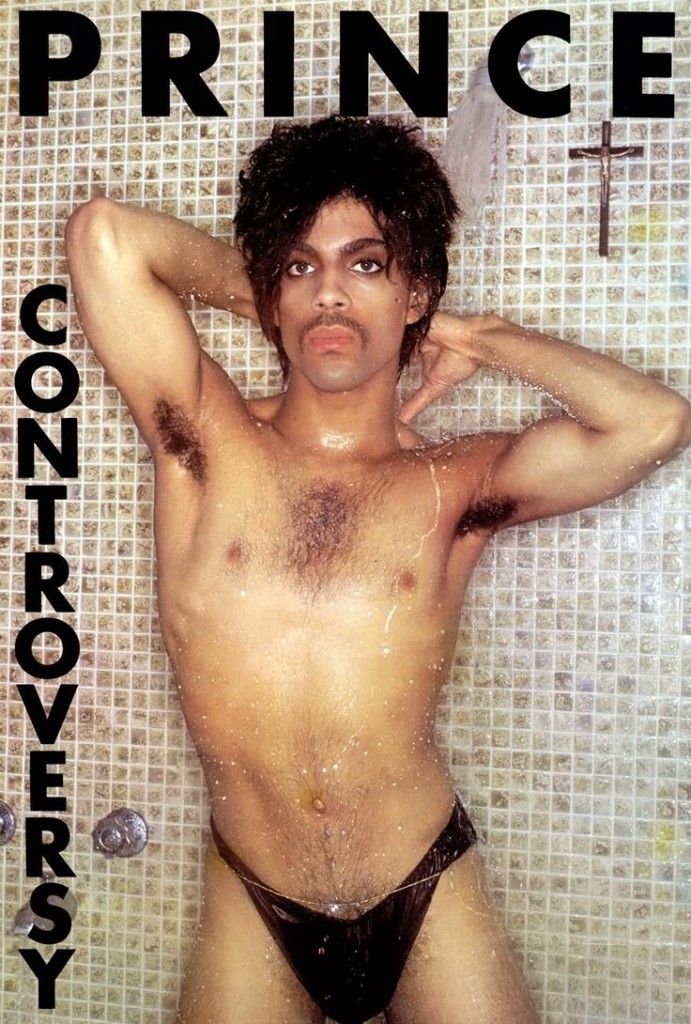

For us teenagers, Prince created dance music that allowed our bodies to pulsate with the kind of feelings religious parents want to pray out of you. My Catholic mother was no exception. My sister put up a poster from Controversy, with Prince in a shower with the tiniest of briefs on, his wet pubic hair glistening, and his belly chain shining. His hands were clasped behind his head and over his left shoulder hung a crucifix. Boy howdy. I stared at that picture intently more than I would like to admit—at least until my mom tore the poster off the wall in disgust.

The only other man allowed in our house dressed in similar fashion was Jesus on the cross, and he wasn’t sexy at all. Prince was sexy. His hair flowed like silk, and he sang songs that made your skin heat up. He was a black man who had the nerve to walk around with a perm in his hair, and in his “draws,” as the old folks would say. My sisters and I loved Prince because he was free: sexually liberated, not afraid to touch his body—or anyone else’s for that matter.

Prince sang about God too. For repressed Catholic girls, Prince was like dynamite. He woke something up in us that has not gone out since. Later my mother would relent and allow me to take my sister to a Prince concert, the one where he brought a whole bed on stage. That was epic. When my mother asked how the show was, we just said it was “good” without going into details.

That kind of brazen sexuality, mixed in with God, scared parents. Tipper Gore went after Prince after hearing her daughter listening to “Darling Nikki,” and started a whole campaign against his music. In the midst of the Reagan era, Tipper Gore would head up the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) and hold court during senate hearings on the “filthy fifteen” (including, of course, Prince’s “Darling Nikki” and “Sugar Walls,” with lyrics sung by Sheena Easton). The upshot was that the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) agreed to label records with offensive lyrics—which really just made it easier for all of us to get the music we really wanted.

Later, after becoming a Jehovah’s Witness in 2001, Prince would self-censor his lyrics. His conversion might have seemed strange after his sex-suffused lyrics, but in some ways it was a natural extension of his Seventh Day Adventist upbringing. Both religions arose during the 19th century ferment around millennialism, health, and purity, themes that have threads in much of Prince’s work. He still was Prince, but became a more sober version of himself, turning vegan, talking more openly about his religion. Sex remained in his lyrics, but it was much subtler, and not so frenetic.

Prince Rogers Nelson grew up, and so have all of his fans, especially those who knew him from the start and followed his career avidly. We knew his music, but we didn’t know the Prince that Van Jones and many others knew, the philanthropist who helped in quiet, important ways in Black communities. Always a private person, Prince did his good works without fanfare. Battles wage already on Facebook about Prince’s legacy, and some smug Christians disavow him because of his lyrics.

Prince was a better Christian than those who are critiquing his lyrics, or his life. He knew what it was like to have desire, both for God and for the flesh.

I’ve had a hard time writing this piece, because I know when I’m finished with it, a part of my youth will have died. There is nothing worse than having a loved one die, but the moment an icon of your youth dies is the moment that your youthful memories feel as though they are being snatched away, and the chasm of death looms large.

Prince’s death is like that for me. The chasm is real. Yet in grief, Prince songs can still make me smile, get from behind my desk to shake off death, and imagine better days.

Rest well, dear Prince. I can’t wait to hear the music you’ve left behind.