What inspired you to write Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism?

There’s a story I tell near the beginning of the book: I was in the midst of researching and writing the book, and a group of leaders of Jewish men’s groups invited me to speak. They were full of questions about masculinity, about men and religion, and about how and if men of different religions had different masculinities. What made men participate in Judaism? How could their groups make Judaism appealing to men? When I said that I wish I knew, they enthusiastically invited me to “Study us!” I’m not a sociologist so I couldn’t take them up on their generous offer, but in that moment I realized that neither scholars nor people within Jewish communities really have a good understanding of masculinity, how it works, or why it matters. I think the book is a start toward that better understanding.

I also knew there was a scholarly need for it. I had been writing about American Judaism and gender more generally, and one reviewer wrote something like “this piece says it’s on gender, but half of it is about men!” Around the same time, an edited collection of essays, Gender and Jewish History came out, but only one of its 21 essays dealt with masculinity. In a lot of American Jewish history, “gender” still seems to mean “women.” And so I knew that we were overdue for a study about American Judaism and masculinity—not just another story about Jewish men, but a story about what manliness has meant, how men have imagined their own manliness and the manliness of other groups, and why these varieties of manliness matter for Judaism.

Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism

Sarah Imhoff

Indiana UP

March 2017

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

Neither gender nor religion is ahistorical. Neither is a constant across time and space. People use the things around them to construct the ideas, values, and practices associated with each, and these change over time and vary across cultures. In addition to this, one of the most important points of the book is to show how religion and gender are very much involved in the construction of one another: the book is the story of how religion shaped American Jewish masculinity in the early twentieth century, and it is also the story of how masculinity shaped American Judaism.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Of course! As it is, the book has chapters about American Jewish philosophy, religious conversion, the American west, Jewish identification with “Indians,” agricultural schools, Zionism, crime in New York, the Leo Frank case, and the Leopold and Loeb hearing. It would have been great to write chapters about sports, or about World War I, or about philanthropy, or about film. Or about ten or twelve more things I can think of. But there was no way I could cover every aspect of American Jewish life, and so I tried to choose topics that illustrated the big themes I saw.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

There is a general assumption—I don’t think it’s often articulated—that men’s gender roles are consistent. We have books about “the changing role of women” in any country you could pick, we talk about how different cultures or religions “treat women,” and we (rightly) celebrate the progress countries have made for women’s rights, but underlying much of this is the sense that masculinity stays the same, or that it’s somehow given, unlike the cultural contingency of femininity.

There is a general assumption—I don’t think it’s often articulated—that men’s gender roles are consistent. We have books about “the changing role of women” in any country you could pick, we talk about how different cultures or religions “treat women,” and we (rightly) celebrate the progress countries have made for women’s rights, but underlying much of this is the sense that masculinity stays the same, or that it’s somehow given, unlike the cultural contingency of femininity.

We have an awful lot of books about men, so why write another, you might ask? I asked myself this question because women are far underrepresented in historical scholarship. We surely don’t need another book that studies men because it assumes their thoughts and experiences obviously represent everyone’s thoughts and experiences, or one that assumes that men are the default human beings and women are a special case. But this book is about masculinity, and it unearths cultural assumptions about what it meant to be a man in general and a Jewish man in particular. Studying masculinity in this way is crucial to having a larger understanding of how gender works and how gendered assumptions get taken up.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

I tried to juggle several academic audiences—people who write about American religion, people who do Jewish studies, and gender studies scholars—but I also really wanted undergraduates to read it. As a teacher, I’ve often wished that there was better stuff for my students to read to help them understand how different masculinity can be in different places and times.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

My main goal was to inform, even to reorient people’s thinking about how American Judaism came to be the way it is. But the book makes a few foundational assumptions that might piss off certain corners of the academic world. Methodologically, it runs against the grain of conventional Jewish histories. It refuses the terms “Jewish identity” and “the Jewish experience” because they imply that Jewishness has some unified meaning. Also, and here’s the real rub, I think, I did not begin my research with the assumption that Jewishness necessarily meant difference, or that Jews were always “the other.” I did not assume that Jews were forever defining themselves over against non-Jewish norms. The book does not take Jewishness as the marker of the “one true self” or assume that Jewishness is the most essential piece of the selves of people called Jews. My method began with agnosticism about whether and how Jews were different from one another and from their non-Jewish neighbors when it came to imagining Jewish masculinity. In the end, they were different—but they were also the same. And I wanted to make sure both sides of this story were told.

What alternative title would you give the book?

I really wanted to go for the keywords here. In many ways, it’s covering some new territory in the history of American religion, so I went straightforward rather than clever. I suppose I could go for something snarky, like Men Have Gender Too: The American Jewish Edition.

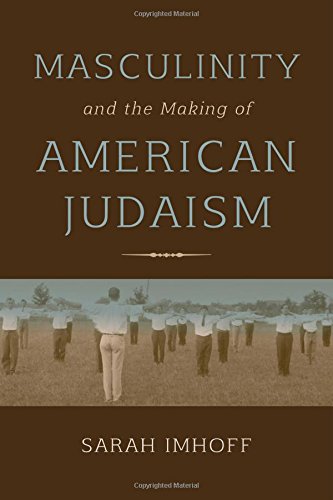

How do you feel about the cover?

I love it. I found that photo in the archives, and I was captivated. Here they were: a bunch of men standing in a field doing calisthenics! In collared shirts and ties! At a colony designed to train Jews to farm! It suggested so many of the themes about manliness I had seen: farming the land, physical fitness, clean dress, and a general decorum and orderliness. But it also hints at the weirdness (and even impossibility) of gender expectations. These men are supposed to be both clean and rugged, to be workers but to be genteel. Also the picture is from Woodbine, NJ, so it’s a little shout-out to my home state.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

Last summer I read Sy Montgomery’s The Soul of an Octopus. It is, in fact, pretty much what it sounds like: a popular science book about octopus cognition, physiology, and behavior. I’m an avid scuba diver, and the octopus is one of my absolute favorite creatures. They’re smart, they’re expressive, and they will look right at you as they dig into a conch shell for lunch. But I also loved the book because it makes the reader think about how humans know what we know, how our senses work, and how our bodies work (or don’t). I’m captivated by the natural world, something that doesn’t appear much in Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism, but that will make appearances in my next book.

What’s your next book?

It’s a series of stories about Jessie Sampter, a queer disabled Zionist woman who lived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I have often told graduate students that nothing is intrinsically interesting, since I came across Sampter’s writings in the archives, I have been increasingly moved to change my mind. She moved to Palestine alone in 1919 and gave up her American citizenship. But most interesting of all, to me, is that she was disabled from childhood polio, and she never married, but she championed a Zionist movement that promoted settling working the land and having children. How did a queer, “crippled” woman become a leading voice of American Zionism, and how should I write about the life and embodied experiences of this woman who defied social norms and confounded available categories of sexuality?

Although Sampter seems exceptional, there is something far more typical in her life and thought. And this has become one of the driving questions of the book: What do we tell ourselves when our embodied lives don’t match our political and religious ideals? How do we make sense of it? I’ve read several thousand pages of Sampter’s writing, at least as much from her friends, family, and Zionist associates, and the fact remains that there is no easy answer. That’s one of the reasons I think her story is going to be terrific.