Earlier this year, on his Straight White American Jesus podcast, RD’s Bradley Onishi spoke with Dr. Lerone Martin about his latest book. In this edited and condensed version of their conversation, Martin, an associate professor of religious studies at Stanford, discusses J. Edgar Hoover’s contributions to leading evangelical magazine Christianity Today, the lengths he went to in his crusade against Martin Luther King Jr, and of course his pivotal role in the construction of White Christian nationalism in the US. – eds

***

The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover: How the FBI Aided and Abetted the Rise of White Christian Nationalism

Lerone A. Martin

Princeton U. Press

Feb, 2023

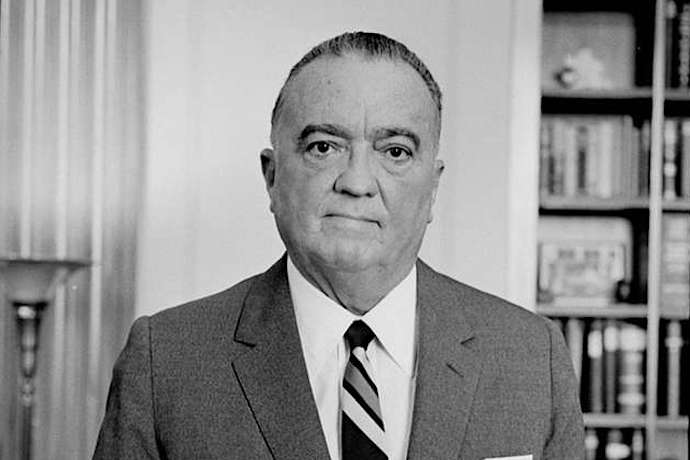

Dr. Lerone Martin: Hoover was raised in the Presbyterian church and he talked a great deal in his childhood diary and his adulthood about how important his upbringing was in the Presbyterian church. Hoover taught Sunday school from the time he was 13, rising through the ranks to become secretary. He was the captain of the cadet team at his high school and he wore that uniform to teach his Sunday school classes. So we get a sense that as a young man Hoover’s committed to a kind of muscular idea of Christianity, that Christians are to be soldiers, there to protect America’s Christian soul.

One of the central claims of your book is that Hoover and his FBI should be seen as central to the building of Christian nationalism in the middle 20th century.

Hoover led the FBI for almost five decades from 1924 to 1972, and he announced to his agents at one point that their job was “to perpetuate and defend America’s Christian endowment.” And Hoover did that in a couple ways. The first thing he did was to have agents sign what he called a “law enforcement pledge” that said in part that agents would commit to being “soldiers” who would “wage vigorous warfare against the enemies of my country, of its laws, and of its principles.” They were also meant to act as “ministers.”

And Hoover makes sure that his agents are cultivated this way by putting them through a series of religious exercises. He also initiates an FBI Communion breakfast for agents and their families to come to mass, to hear sermons—especially those that point out how they are the defenders of America’s Christian soul. And so all of this of course really accelerates during the Cold War as America’s trying to defend itself against Russia and defines its war with Russia as not just an actual physical war, but a Cold War.

How did Hoover connect with Christianity Today?

Christianity Today is a new magazine in the fifties. It’s just starting out. And they’re trying to connect with prominent individuals that they believe will help to bolster this new thing they’re calling “neo-evangelicalism” or “modern evangelicalism.” And they reach out to Hoover and ask him to be one of their contributors to the magazine. And Hoover does that. Hoover writes for Christianity Today beginning in the fifties.

And one of the things that’s so fascinating about this, is not only does he write for them, Hoover has someone on staff who has a PhD in history from Washington University in St. Louis. His name is Special Agent Fern Broker and he’s a Methodist layman. His job is to go to the office of Christianity Today to connect with Carl F. H. Henry and figure out what J. Edgar Hoover should say or would say.

Fern Broker writes it, Hoover approves it, and then it’s published in Christianity Today under Hoover’s byline. And then these essays are printed at the FBI printing office—stamped with the FBI emblem of approval. And at the bottom it says, “reprinted from Christianity Today.” And so the FBI distributes Hoover’s essay throughout the country to people who write in and ask for assistance or help. And then Hoover also sends this to special agents across the country in FBI field offices.

And so these essays for Christianity Today are not just essays, but they’re distributed by the federal government almost as if it’s official government policy.

Could you talk a little bit about the FBI’s involvement in local churches?

Hoover would have his agents at times attend these FBI Vesper services at various Protestant churches. Hoover would actually have them participate in worship. And so they would read scripture, they would lead songs, they would do the opening prayer—and they were very welcomed in evangelical churches.

And he found many Protestant churches lacking in that area, so it was welcoming of Catholics—but not welcoming of African Americans. The FBI was forced by the Kennedy administration in 1962 to hire African American special agents because Hoover had thrown them all out when he became FBI director in 1924. In my interviews with these African American agents who worked under him, they all told me they were never invited to these worship services. Some of the agents I interviewed didn’t even know these worship services existed. And so there was a moment of patriotic Christianity that valorized and authenticated the idea of racial segregation as being in line with God’s order.

This reminds me a lot of what Perry and Gorsky write in The Flag and the Cross about how Christian nationalism is really about order and freedom. And the idea there is that the White Christian has the sole authority to use violence to put the social order in its proper place.

Absolutely. One of the well-known lines Hoover wrote is: “The criminal is the product of spiritual starvation. Someone failed to teach him and lead him to God and to learn God’s ways.” So Hoover always equated crime with a lack of spiritual commitment. Crime is about sinful, evil, spiritual forces at work. Hoover, despite modernizing the FBI and bringing science to it in terms of solving crimes and evidence, still always went back to this idea that crime was primarily something that was only spiritual. He refused to engage in any kind of sociological explanations of crime.

He always went back. If you commit crime, there’s something wrong with you. You are spiritually starved. And all we really need to do is to have a revival to go back to America’s supposed glorious Christian founding, and then crime would be solved. But because we have forces at play in this country who don’t wanna go back to the founding, that’s why we have crime.

It seems as if Hoover was sort of convinced that the proper social order is one in which the races were separate.

Hoover has this amazing line that he gave to some reporters in 1965, right in the midst of the voting rights campaign that Martin Luther King Jr. was involved in. He says that despite all the violence that’s going on in the South, White people for the most part are good people. He almost justifies the kind of violence that’s happening because African Americans are asserting their right to vote.

And then he says, African Americans, for the most part, are uneducated. They’re not smart, and they’re not ready to vote. In fact, he says that many of them, if they had the opportunity, probably wouldn’t even vote. So he says what they need to do is to focus on their own piety, their own morality. And then, slowly but surely, they will have rights equal to that of White citizens. And so Hoover has this idea that African Americans are in the condition they’re in, not for sociological reasons or because of legal segregation. It’s because of their lack of morality.

Can you help touch on some of the interactions between Martin Luther King Jr and J. Edgar Hoover?

Absolutely. The FBI is so important in helping to peddle this image of King as a communist. And the FBI did so in a number of ways. They investigated King and his “communist” connections even when the FBI realized that the communist connections were not there. So the FBI takes it into its own hands. And they begin not only to surveil Martin Luther King Jr, but to engage in counterintelligence.

They sent him a letter, an anonymous letter, telling Martin Luther King Jr. that he was immoral; that he was a beast and that Satan could do no more [evil]. And then, in order to help to launder some of this counterintel, they connected with an African American evangelical by the name of Elder Lightfoot Solomon Michaux, who had a CBS radio show across the country and was the first minister, Black or White, to have his own television show.

Elder Michaux was in cahoots with the FBI. He laundered some of the FBI’s counterintelligence about King by putting it in his sermons and in his broadcast. He demanded that Martin Luther King Jr. apologize to the FBI, and put it in the sermon, put it in a public letter, and issued it to the news, also verifying the claims that King was a communist. So the FBI was very successful in trying to paint King, not as a minister who’s advocating for America to live up to what it said on paper, but as a minister who’s bent on destroying America.

And I think what’s important for us in our own moment to learn from this is how the FBI never really dealt with King’s claims about African Americans being treated unfairly. It simply used the label of “communist,” which then allowed them to dismiss everything he said. And I think that we can see that in our own politics today. Instead of dealing with political claims, we just label them today as “socialist” or we label them as something “extreme.” And then you don’t have to actually listen to them.