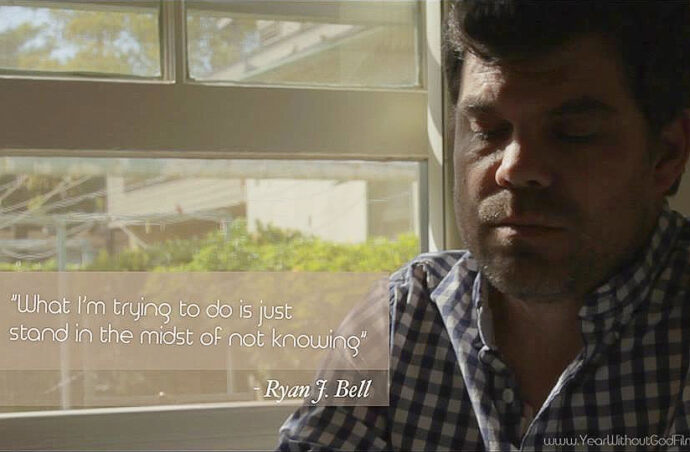

Ryan Bell no longer believes in God, exactly. Bell is the former Seventh-Day Adventist pastor who last January made a resolution to live as an atheist, to live for a “year without God.” More precisely, Bell decided to take a year to explore “the limits of theism and the atheist landscape in the United States.”

On the surface, it sounds a little gimmicky, and his critics have often portrayed his decision to “try on” atheism as little more than a carefully-crafted media stunt of a typical genre.

If it was all a stunt, it may have not been a very good one, at least in the near term. He apparently hasn’t immediately profited from it. Bell’s decision caused him to lose jobs counseling students and teaching part time at Fuller Theological Seminary and Azusa Pacific University, and so by his own admission he’s “only lost money and earning potential” during the year. A decent book contract might promise to make up for lost capital, but he doesn’t have one—at least not yet.

I would argue that Bell’s public embrace of atheism is more a natural outcome of his own personal and professional trajectory than a strained gimmick. In an interview he did with NPR last January Bell indicated that, as far as he can remember, he has always wrestled with his faith.

Indeed, for Bell that’s just what faith is: it’s “one of those things that people wrestle with.” Some in his former congregation didn’t seem to think so, however. It was his expression of some of those doubts that had led to his forced resignation the year before. Bell said in the same interview that after he lost his leadership role in his congregation, “he really didn’t have any compulsion to go to church internally” and “just didn’t feel like participating in church,” even though he “tried a number of times.” Eventually he decided to stop trying, and then “began to wonder about the very existence of God.” And thus began his yearlong experiment.

The year being up, Bell now says that he doesn’t believe that God exists: “I think that makes the most sense of the evidence that I have and my experience. But I don’t think that’s necessarily the most interesting thing about me.”

Whatever one makes of that conclusion and the intellectual and existential analyses that got him there, even a quick read of his blog shows his thoughtfulness, honesty, and humility through the whole process. For that, I think, he is to be admired. Not everyone thinks so, of course. Reactions to Bell’s admission of atheism among some critics have ranged from accusing him of being “angry” and “never having a relationship with God in the first place” to expressing pity and, at worst, hatred for him.

I could say a lot here about the relationship between faith and doubt, but I think it’s even more interesting to set Bell’s experiment in the context of all the worries over people, especially the so-called millennials, leaving churches. Much has been made in the past few years about this trend, which is not so much a mass exodus as a slow leak that, as I’ve said before, has its roots in a larger cultural process. The overall decline in regular church attendance and membership, especially among younger generations, is obviously a concern for church leaders and the faithful of all stripes, who rightly see the future of their respective institutions at stake.

Generally speaking, the response to this decline takes the form of some sort of repackaging. That is, it is assumed that the problem is not with the substance of Christianity. At its core, the thinking goes, the gospel or “good news”—that we are “sinners” who can find “salvation” through the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, the Son of God—remains a vital truth, one which all need and ultimately seek, whether we consciously know it or not. That basic assumption remains the case even in more liberal Christian circles, I would suggest, although it often takes the form of respect for other religions and/or an emphasis on the importance of spirituality, broadly defined.

In this way of thinking, people are not leaving the church because of its central message but because of the way that message is or is not presented. Hence the calls among some in more evangelical circles, for instance, for the abandonment of the skin-deep flashiness and alienating culture war rhetoric for a kinder, more authentic—and ultimately more attractive—faith.

There is something to that line of thinking. More than a few have left churches from a lack of authenticity—and feel a great sense of loss in doing so. Such emigrants would, perhaps, gladly return if offered something better. But that way of understanding the situation can not account for what Ryan Bell experienced.

What’s striking to me is the matter-of-fact way in which Bell describes that experience. In the interviews he’s given, there’s hardly any pathos, any handwringing over the faith he can no longer identify with. Rather than rehearsing a litany of loss and pining over something more authentic, he sees his shift away from religion as an opportunity, a window into what, for him, really matters.

Christianity is something that, ultimately, he no longer needs.

At a more general level, the recognition that religion’s utility has run its course is precisely what Nietzsche referred to as the death of God. Thus, when asked earlier this month what he thought was the most interesting thing about him, Bell responded,

“I think what is far more important to know about me is the way I choose to live my life. Once people have come to terms with the weaknesses or falsehoods in their belief system, the work has just begun. How we reshape or build the narratives by which to live our lives is the most interesting part of our work as human beings. My work to end homelessness, my interest in the crises facing our democracy and our ecosystem—these are the interesting aspects of my life and work. At least, I’d like to think so.”

I suspect that there are many former believers out there who feel similarly. Perhaps they call themselves atheists, perhaps something else—but either way they have become largely indifferent not only to the packaging of Christianity but also to its very message. Such individuals, moreover, likely won’t return to Christianity and its churches no matter how “authentic” the latter become, because they feel as if they’ve lost nothing and thus have nothing to gain through returning. The utility of their former beliefs and the structure that maintains them has run its course.

What should churches do with that knowledge? Ignoring it or covering it over in the language of authenticity—or, even worse, demonizing those who have dropped away—certainly isn’t much of response. As Nietzsche knew, the ‘death of God’ requires that we push all the way through it, even if we’re not comfortable with the outcome. Bell seems to have understood that much, at least, even if his critics haven’t.