In a May 13th article published in The Atlantic, Adrienne LaFrance offers her readers a deep dive into the QAnon movement. The article argues that when surveying QAnon, we’re not only examining a conspiracy theory, we’re observing the birth of a new religion. LaFrance underscores this argument by highlighting the apocalypticism found in QAnon; its clear-cut dualism between the forces of good and evil; the study and analysis of Qdrops as sacred texts, and the divine mystery of Q.

Following the mass suicide of the Peoples Temple in Jonestown in 1978, historian Jonathan Z. Smith wrote an essay locating the study and definition of religion within an academic context, where he highlights that “almost no attempt was made to gain any interpretative framework” of what occurred at Jonestown by academics. Adrienne LaFrance’s article on QAnon makes clear that the movement and its believers demand to be taken seriously. Her piece acts as a springboard to ask the question: Can QAnon be considered a religion?

Though many enjoy mocking the QAnon conspiracy theories and those who profit from them, it’s important to note that the movement’s adherents firmly believe in the theories—even to the detriment of their families and communities. Therefore, in an effort to avoid the mistakes of the past and to better understand the movement as it continues to grow and evolve, I suggest that we view QAnon as a “hyper-real religion.” Sociologist Adam Possamai, who coined the term, defines it as “a simulacrum of a religion created out of, or in symbiosis with, commodified popular culture which provides inspiration at a metaphorical level and/or is a source of beliefs for everyday life.” Or, to put it more simply, a religion with a strong connection to pop culture. This concept, based on Jean Baudrillard’s work on hyper-reality and simulations, was proposed to me as a possible way to understand QAnon by my colleague Martin Geoffroy. Hyper-real religion is based on the premise that pop culture shapes and creates our actual reality, with examples including, but not limited to: Heaven’s Gate, Church of All Worlds, Jediism, etc. As a movement in a constant state of mutation, QAnon clearly blurs the boundaries between popular culture and everyday life.

What this means is that technology and the marketplace of ideas have inverted the traditional relationship between the purveyors of religion and the consumers of religion. Thus, we see religious doctrinal authority (that is, those who can contribute to the religion’s teaching) being created by popular culture.

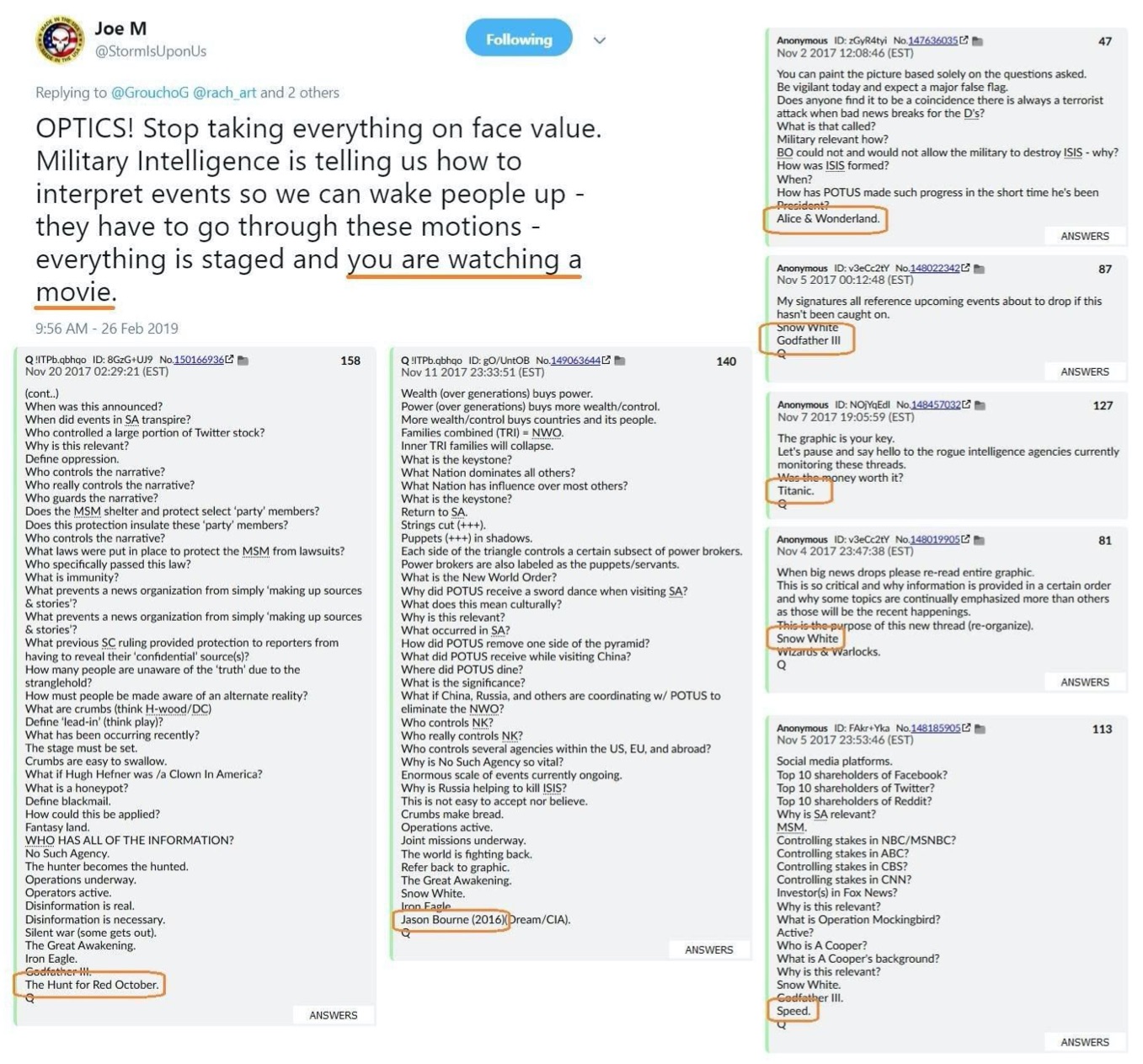

For example, the QAnon cosmology (how the world/universe appears; what it looks like; its characteristics, and types of creatures that populate it) and anthropology (ideas about human beings, their origin and destiny) are rooted in conspiracy theories, historical facts, and mythical history from film and popular culture. As such, Terry Gilliam’ Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is recommended by QAnon followers as evidence of the effects of Adrenochrome; The Matrix’s blue pill/red pill scene is used to frame the choice to either be a part of the Great Awakening or to remain “asleep”; and the slogan “Where We Go One, We Go All” is from the film White Squall, whose official YouTube trailer’s comments section is filled with QAnon followers (the top-rated comment, with over 5,000 up-votes, reads “Thumbs up if Q sent you here”). The prophetic figure of the movement, known only as ‘Q’ , also regularly references movies in their QDrops, as demonstrated from the screenshots below:

The QAnon theology (conceptions of the sacred, gods, spirits, demons, the ancestors, culture heroes and/or other superhuman agents) is rooted in American evangelicalism and neo-charismatic movements developed in the 1970s and 1980s—specifically theology involving a worldwide cabal that controlled governments and aimed to control the freedoms of people through technology, medicine, and liberalism. For example, QAnon reworked elements of the Satanic Ritual Abuse (SRA) panic (aka “satanic panic”)that originated in the U.S. in the 80s. SRA was the belief that a global network of elites was breeding and kidnapping children for the purposes of pornography, sex trafficking, and Satanic ritual sacrifice.

Furthermore, QAnon adopts the language of spiritual warfare found in many neo-charismatic movements. Based on some of the data analytics work I’ve done, Ephesians 6:11-18 is the most shared verse among QAnon adherents. Given the verse’s apparent condemnation of governments, the reaction of QAnon to the pandemic is rooted in the language of spiritual warfare, especially when addressing conspiracy theories surrounding 5G, ID2020, Bill Gates and vaccines, HR 6666, etc. Since the start of the pandemic, QAnon have spread a false racist theory that Asians were more susceptible to the coronavirus and that white people were immune to COVID-19; they’ve promoted drinking bleach to cure the virus; that COVID-19 is a Chinese bioweapon and that the virus release was a joint venture between China and the Democrats to stop Trump’s re-election by destroying the economy. If that weren’t enough, they also played a key role in promoting the Plandemic video and the ObamaGate and #FilmYourHospital hashtag; and forced Oprah Winfrey and Hilary Duff to come out with statements declaring that they are not pedophiles.

When taking into account how much neo-charismatics, American evangelicalism, theological conspiracy theories, and spiritual warfare is influenced by the distrust of the everyday reality as being false (with their reality being ‘true’), one could make the argument that QAnon theology is not only influenced by pop culture, but is in fact, deeply rooted in the conception of the sacred within a hyper-real world.

Some might argue that a hyper-real religion isn’t a “real” religion because it’s invented, but scholars of religion don’t validate or discredit claims of what constitutes ‘true’ religion, because it’s true to the people we study. As a scholar of religion I study what people do when dealing with the sacred, rather than try to validate the religious message or experience. What people do when dealing with the sacred is routinized over time as believers construct their religion. All religions, hyper-real ones included, are socially constructed and are thus invented. QAnon is blatantly invented as it openly uses works of popular culture, media, entertainment, American evangelicalism and conspiracy theories at its basis, that have been organically developed across time and space by a community of believers. Belief in QAnon reflects a created hyper-real world based on such theories.

This is unsurprising, as Travis View stated on PBS’s The Open Mind “we’re living in an age where conspiracy theories are promoted at the highest levels of power, when it wasn’t that long ago conspiracy theories were the pastime of the powerless.” Similarly in 2018, Joseph Uscinski stated that QAnon is different from normal conspiracy theories. “Conspiracy theories are for losers,” he told the Daily Beast’s Will Sommer, “you don’t expect the winning party to use them.”

By framing QAnon as a hyper-real religion, it can offer insight into the confusion that people feel when discussing the movement, which is critical for observers, scholars, and decision-makers who need to take QAnon seriously. The past months have highlighted how QAnon is a public health threat, a threat to national security, and a threat to democratic institutions.

The essence of conspiracy beliefs like QAnon lies in the attempts to delineate and explain evil; it’s about theodicy, not secular evidence. QAnon offers comfort in an uncertain—and unprecedented—age as the movement crowdsources answers to the inexplicable. QAnon becomes the master narrative capable of simply explaining various complex events and providing solace for modern problems: a pandemic, economic uncertainty, political polarization, war, child abuse, etc.

The result is a worldview characterized by a sharp distinction between the realms of good and evil. The movement accomplishes this by purporting to be empirically relevant. That is, they claim that QDrops are testable by the accumulation of evidence about the observable world in fighting evil. Those who subscribe to QDrops are presented with elaborate productions of evidence in order to substantiate QAnon’s claims, including source citation and other academic techniques.

However, their quest for decoding QDrops masks a deeper concern: the more sweeping a conspiracy theory’s claims, the less relevant evidence becomes—notwithstanding the insistence that QAnon is empirically sound. At its heart, QAnon is non-falsifiable. No matter how much evidence journalists, academics, and civil society offer as a counter to the claims promoted by the movement, belief in QAnon as the source of truth is a matter of faith rather than proof.

Therefore, rather than ask questions like, How can people believe in QAnon when so many of its claims fly in the face of facts?, we should instead ask What are QAnoners doing with their belief system? QAnon believers have committed acts of violence in response to QAnon conspiracy theories. Elected officials or those campaigning for elected office have campaigned on QAnon. Those studying and combating the movement need to move beyond viewing it as a mere conspiracy theory; QAnon has grown beyond that. We are, as Adrienne LaFrance asserted, witnessing the birth of a religious movement. QAnon as a belief system only appears to be dependent on Donald Trump’s presidency and his ability to remain in power. Whether we will be speaking of future or former President Trump, the person known as Q will likely fuel the movement for a long time to come. Q will continue to claim special insights, knowledge, and frame things for their followers in terms of their enemies’ alleged ambitions.

If Donald Trump wins in November, QAnon will be vindicated in their beliefs and say this is what God has mandated, reinforcing the belief that they are right. If Trump loses, it will be attributed to the Deep State Luciferian cabal and they will have a role to play in fighting against the fake government that’s replaced Donald Trump.

QAnon has become a hermeneutical lens through which to interpret the world. Already we’ve seen a formalized QAnon religion at Omega Kingdom Ministries (OKM). OKM is part of a network of independent congregations (or ekklesia) called Home Congregations Worldwide (HCW). The organization’s spiritual adviser is Mark Taylor, a self-proclaimed “Trump Prophet” and QAnon influencer with a large social media following on Twitter and YouTube. At OKM, QAnon is a hermeneutic by which the Bible is interpreted; and the Bible, in turn, serves as an interpretive lens for QAnon. Furthermore, QAnon is built into their evangelical Christian rituals. OKM may be a sign for what’s to come in terms of QAnon’s proximity to evangelical and neo-charismatic movements in the U.S.

In categorizing QAnon as a hyper-real religion rather than a decentralized grouping of conspiracy theorists, it provides an analytical framework to quantify and qualify QAnon-inspired acts of violence as ideologically motivated violent extremism. Furthermore, there’s an increasing overlap between QAnon and the far-right/Patriot movements on Telegram, a messaging app that has attracted extremists because due to its privacy protections. From the perspective of national security, we need to be prepared for more acts of violence by QAnon believers as it’s proven to be a catalyst for radicalization to violence, terrorism and murder.

By considering QAnon as a hyper-real religion, it becomes possible to frame how QAnon has found resonance not only within the American electoral system, but with populists around the globe. This is especially important not only in the context of elections, but also when framing the global response to the pandemic and public health. Policy makers at all levels need to take the QAnon ideology seriously when planning strategies to mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus.

QAnon may not be a recognized religion, a tax exempt 501c3 institution, or the kind of traditional brick-and-mortar religion most are familiar with. However, by framing QAnon as a religion—in particular, a hyper-real religion—we create a framework that helps us better study, report and understand QAnon. More importantly, it demonstrates that the movement needs to be taken seriously and has the socio-political and behavioral impacts that other religions have. In doing so, it provides a pathway to protecting our societies and institutions from the public health, democratic, and national security threat that QAnon potentially poses.