The Public Eye, Fall 2023/Winter 2024 (Issue 108)

“Democracy Under Attack—And How We Fight Back,” examines antidemocratic forces on the Right and pro-democracy efforts to counter them.

Inform your resistance: Subscribe now!

In her book, Innocent Until Proven Muslim: Islamophobia, the War on Terror, and the Muslim Experience Since 9/11, Hilal analyzes the narrative and political mechanisms that enable the War on Terror; its institutionalized Islamophobia as entrenched in the state’s laws and policies; and how Muslims internalize, reproduce, challenge, and live with these injustices.

Alongside its domestic impact, Hilal examines the global scope of the War on Terror’s systemic imperial violence and torture in state memos, reports, case studies, and detainees’ stories. The latter includes the stories of men like Omar Khadr, detained at Guantánamo Bay at the age of 15, and Abu Zubaydah, Guantánamo’s “forever prisoner,” who the U.S. has held without charges since 2006.[2] Their continued detention relies on dehumanizing state narratives that portray Muslims and Arabs as violent, vengeful terrorists—beasts lacking humanity that require subhuman violence to tame, and in some cases, eradicate. In reaffirming its right to surveil, contain, and brutalize Muslims suspected of being terrorists anywhere in the world, the United States upholds systems of prison imperialism—producing CIA black sites, and more renditions, torture, prisons, and terrorists—at home and abroad.

The decades-long War on Terror and its violence toward Muslims is a bipartisan priority despite its conservative origins. While George W. Bush signed the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) bill, his successors—two Democratic presidents and one Republican—upheld the AUMF. This, Hilal writes, “has allowed the War on Terror’s global military footprint to expand exponentially—rippling out from the initial conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq to touch nearly 40 percent of the entire world.”[3] The Bush Doctrine thus remains core to U.S. war making and policies for managing populations at home and across the globe.

PRA spoke with Hilal in early December about the pervasiveness of War on Terror narratives, her visit to Guantánamo, and Muslim humanity.

PRA: You introduce your book as a thought project happening in the moment of the George Floyd protests. Can you speak more about why you describe it this way?

Dr. Maha Hilal: There are a lot of reasons why. Number one: the protests were significant. Unfortunately, White Americans don’t understand the gravity of this country’s violence, even though it’s happening in the backdrop, every single day. Around that time, people were talking about the 1033 program,[4] and how the War on Terror was coming home. I thought that was interesting because the War on Terror has been at home. It started at home while it was being launched abroad. So, I wanted people to know that the violence of the War on Terror is continuous and has been here from day one—but also that these multiple systems of violence are occurring at the same time. Anti-Black violence has been part of this country from the beginning. People began to understand; although the War on Terror started after 9/11, they were connecting the dots between these different types of state violence. That’s important because Black people’s struggles in the U.S. have led to many of us having [civil] rights we otherwise wouldn’t have had.

In the book, you write about visiting Guantánamo, which surprised me as a reader. Can you talk more about it?

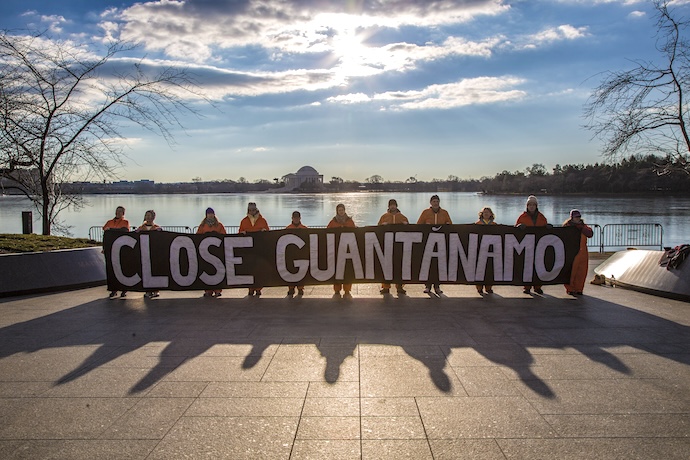

I’ve been part of this group called Witness Against Torture for many years now. In 2015, we went on a delegation to Guantánamo City to get as close to the prison as we could, to call for its closure with the men to be transferred out of it. We couldn’t get very close because we were approached multiple times by Cuban government officials asking us not to go because it would cause trouble [with the U.S.] for them. It was a delicate place, because we were a group of Americans and didn’t want to cause trouble for the Cuban government, because Guantánamo is a U.S. naval base on their land without their consent.[5] We camped on a big hill where you can kind of see the naval base and prison in the distance. We did all our solidarity activities on that hill. For me, as a Muslim, it was a very powerful experience, but also devastating because you could only get so close. And in my experience, there haven’t been many Muslims involved in efforts to close Guantánamo, calling for an end of the torture. For me, it’s been a main driver of my work, to see the way Muslims have been so criminalized, demonized, and brutalized in the War on Terror and to know that it is because of an identity I share with the men who are being detained.

Even in abolition spaces, Guantánamo is excluded; it seems to be this place that mystifies people, or one they don’t want to touch. Sometimes it’s hard to integrate it into the understanding because people see it as a smaller problem than domestic mass incarceration. It’s an unfortunate piece of the puzzle motivated by how they [the detainees] are narratively constructed as terrorists.

Humanity has been a big theme in discussions of the current genocide[6] in Gaza and the West Bank, and it seems that there is a rupture in the way we are talking about Muslims and Islamophobia. Do you think that the role of humanity in these narratives has changed?

Dehumanization is always there, and the level of violence that’s sanctioned towards a group of people depends on the extent to which they’ve been dehumanized. Muslims have been thoroughly dehumanized in the War on Terror and that’s why Guantánamo exists, why it was okay for the Bush Administration to write memos that the threshold for torture was organ failure and death, and why it’s okay to kill hundreds of thousands in Muslim-majority countries with no accountability whatsoever. So, the dehumanization is pervasive, and I think a lot of why it persists is the way the government talks about it.

Even the construction of “Muslim rage”—what is the purpose of that construction? We know: it’s to construct Muslims as inherently angry and rageful with no explanation for their anger. And because we cannot find a reason, the only solution or intervention is brute force.

You wrote the book twenty years into the War on Terror. What has changed—socially, politically, economically, narratively—since you wrote the book?

Most people seem to think that the War on Terror is over—Biden said this during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, that the war is over.[7] They don’t understand that the War on Terror is much bigger than a visible, active [military] presence in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan, so they believe the war is over. This is also an indication of what war means to Americans domestically. What does it mean for the war to be over? For people in the U.S. versus people in the countries where the U.S. waged violence? It’s a problem because here these wars are out of sight and out of mind.

Obama tried to abandon the “War on Terror” phrase, and to a certain extent, Trump didn’t use it either, so the language is being manipulated. Many in social justice spaces don’t use the term “War on Terror,” but I still use it to stress that it’s a system we otherwise wouldn’t recognize if the umbrella [term] wasn’t there; otherwise, the many ways the War on Terror has been—and continues to be—enacted are treated as discrete and unrelated acts and policies.

In many ways, it’s normalized violence. As we think about abolishing the War on Terror, I wanted to come up with a taxonomy of its violence because it’s so embedded now. This requires understanding the deeply rooted tentacles of normalized surveillance, indefinite detention—whatever it is. How do we de-normalize the War on Terror? How do we de-normalize the ways in which the state has taught us to think about what makes us safe and secure? Much of that “safety” and “security” is on the backs of marginalized communities.

This country needs to fundamentally change its narrative. No matter what happens, the U.S. continues to insist on a mythical narrative about what kind of country this is: that it inflicts violence for good reasons, that we’re good people trying to restore order to bring safety and security. This narrative has been extremely durable. It has served to support any policy of violence the U.S. government wants to implement, making it one of the most insidious, problematic parts of this War on Terror.

Endnotes

[1] Maha Hilal, Innocent Until Proven Muslim: Islamophobia, the War on Terror, and the Muslim Experience Since 9/11 (1517 Media, 2022), 147.

[2] United States v. Zubaydah. Zubaydah was embroiled in a legal battle with the United States government in the Supreme Court over disclosing the details of his torture.

[3] Hilal, Innocent Until Proven Muslim, 59.

[4] Charlotte Lawrence and Cyrus J. O’Brien,“Federal Militarization of Law Enforcement Must End,” American Civil Liberties Union, May 12, 2021. A provision in a 1997 act that allows the Department of Defense to transfer excess military equipment to local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies.

[5] Jennifer K. Elsea, “Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues Regarding Its Lease Agreements,” U.S. Congressional Research Service (August 2022): 3–13. The U.S. naval base’s existence on Guantánamo Bay relies on the 1903 Platt Amendment, which leased Guantánamo Bay and two other pieces of Cuban land to the U.S., in return for the U.S. abdicating administrative control of the newly independent Cuban republic. Since 1964, however, the Cuban government has attempted to abolish the U.S. military’s presence on Cuban land, leading to tense diplomatic, political, and military relations between the two countries.

[6] Center for Constitutional Rights, “Israel’s Unfolding Crime of Genocide of the Palestinian People & U.S. Failure to Prevent and Complicity in Genocide,” October 18, 2023. A crime under international law, legal experts and scholars have analyzed and identified the Israeli government’s current military campaign as genocide. Craig Mokhiber, resignation letter, October 28, 2023. In Former Director of the New York Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights Craig Mokhiber’s letter in response to the UN’s failure to protect Palestinians’ lives and human rights, Mokhiber described Israel’s actions in Gaza and the West Bank as “a text-book case of genocide.”

[7] Trevor Hunnicutt and Steve Holland, “At U.N., Biden promises ‘relentless diplomacy,’ not Cold War,” Reuters, September 21, 2021. Biden referred to the U.S. closing “the era of relentless war” in a statement before the U.N. General Assembly after the withdrawing of troops from Afghanistan.