To bolster a weakened Assad regime, Russia has spent the last few weeks sending military hardware, specialists and even aircraft to Syria. Some argue Putin’s escalation highlights the failures of President Obama’s strategy—if he ever had one. Others believe Putin’s efforts will only save an Iranian ally which is more brutal than ISIS.

Others fear a global conflagration: What if Russian forces accidentally (or worse, deliberately) attack US-backed Syrian rebels? Nor are Russia and America the only nuclear powers involved. Assad’s other ally is Iran, Israel’s arch-nemesis. All of this is enough to keep a calm soul up late into the night. But I have another question. What if Russia’s intervention fails?

And if the Russians lose, who inherits their weaponry?

Sure, it sounds preposterous—how could ragtag Syrian rebels overcome an Assad regime backed by Iran and Russia? But it’s not only possible, it’s probable. Russia is not as strong as it seems.

And the jihadists not as weak as they seem.

Far from strengthening Assad, Putin may be the Islamic State’s dreams come true.

From sea to freezing sea

Modern Russia took shape over centuries, in a sustained expansion that at one point saw St. Petersburg rule all the way to San Francisco. That territory included Muslim-majority regions, conquered territories like the Volga river valley, Crimea and southern Ukraine, and the Caucasus and Central Asia, whose peoples have never fully come to terms with being subjugated. (The lack of real democracy, of course, is a major reason their alienation continues.)

But the Russia that once bested Napoleon and Hitler, that rivaled the United States for global power, has had less luck of late.

If it’s not hard to imagine Russia losing in Syria, it’s because we saw Russia lose badly in Afghanistan, even more surprisingly in Chechnya, and cede tremendous autonomy to the Republic of Tatarstan for fear of losing control of that territory altogether. Today, though Russia barely hangs on to Chechnya and has an economy overly dependent on a single commodity (the price of which has been falling), its dictator has decided to annex Crimea, subsidize a frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine and, of course, double down on the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

Oh, and while Russia’s overall population declines swiftly, its native and migrant Muslim population rises rapidly. Is Putin mad?

Jihadist groups, including ISIS and al-Qaeda, alongside Syrian Islamist forces, relish the idea of fighting Russia directly, although of course Russian involvement bolsters their narrative of defending an abandoned Sunni majority in Syria and minority in Iraq. Not just for the chance to meet the sponsors of the Assad regime directly. Not just because of the nefarious role Russia plays in jihadist lore (remember, al-Qaeda was created in the course of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan); but also for this simple reason: Russian intervention confirms the jihadist narrative, which belongs especially, but not exclusively, to ISIS.

Maybe it’s this vulnerability to ISIS and jihadist forces that makes Russia more inclined to act. In which case, of course, the move smacks less of resolve and more of desperation.

Only a government that has so deeply alienated its citizens could possibly be threatened by a movement so violent and marginal. In which case, Putin is playing into ISIS’ hands. And we should all be deeply worried for it.

It’s time for the end of time

Very much like Christianity, Islam has a rich, contentious, confusing, highly disputed end-times literature, which is mined in times of grave crisis: the arrival of the Crusaders in the 12th century, the onslaught of the Mongols in the 13th, colonial subjugation in the 19th and 20th, and today, with the war in Syria and the crisis of Muslim societies in the Near East.

Broadly, the outlines of (Sunni) Islam’s view of the end times go something like this: The age of just leadership, or Caliphate, will pass, the age of kings will pass, and then there will be tyranny, brutality and oppression. The Muslim ummah will be weak and divided, though nearly uncountable in number. In the darkest hour, a Mahdi—a ‘rightly-guided’ descendant of Muhammad—will be identified at Mecca’s Great Mosque.

He will rally Muslims against oppression without and within, but his success will provoke a bloodier counter-reaction, led by the ‘False Messiah,’ the anti-Christ. When even the Mahdi will be unable to turn the tide, then Jesus, Islam’s actual Messiah, will descend on Damascus, and lead a war to secure an era of global peace and harmony.

There is, of course, much more to what, for lack of a better term, we might call Islam’s Book of Revelation. There is of course tremendous debate and disagreement on what these things mean, and whether they are even legitimate and authoritative texts. But the fact is, a lot of Muslims believe these prophecies correspond to actual events, even if they haven’t happened. The Islamic State’s hold over so many young minds, its ability to recruit and influence them, comes in part from its sophisticated manipulation of this eschatology, its claim to be acting not only in advancement of Islam’s interests, but of those foretold by the Prophet Muhammad himself.

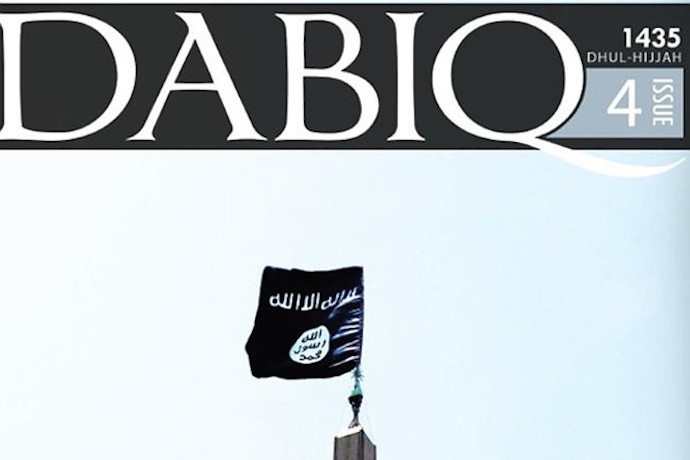

The ISIS magazine, Dabiq, is named for a city where, according to some of these end-times prophecies, a great battle will be waged against Crusader forces. Not to be outdone, al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch, Jabhat an-Nusra (which is at odds with ISIS), named their media outlet “the White Minaret,” after the precise location where it is said Jesus will descend.

And now, ISIS propagandists may well claim Russia’s arrival in the region bolsters their reading of prophecy, and therefore the moral correctness of their approach (as odious as it is). It’s very probable other Islamist and jihadist forces will reach the same conclusion.

Given that ISIS’ war is not an ordinary struggle, with defined objectives and the give-and-take of day-to-day politics, but what Reza Aslan described as “a cosmic war,” a struggle between pure good and outright evil, in which there can be no compromise, Russia’s involvement is a problem. Given Russia’s antagonistic relationship with several Muslim-majority regions, it may not be preposterous to believe Moscow’s Syrian intervention may strengthen ISIS rather than defeat it, and therefore also weaken Russia rather than strengthen it.

It may also be the case that panic over accelerated Russian involvement (on the side of Syria and Iran) will lead countries that do not share ISIS’ eschatology—or at least ISIS’ claims for where it stands in that eschatology—to become more sympathetic, albeit for more ordinary purposes. The enemy of my enemy, after all.

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab nations are, along with Israel, worried about Iran, and willing to use deadly force where they claim to see Iranian proxies. In the past, of course, when terrified of Soviet military might, Saudi Arabia and other Muslim governments funneled weapons and cash to those who would fight them in Afghanistan.

Why would this time be any different?

If only, perhaps, worse.

Our ten years in Iraq accomplished what, exactly? The country is in shambles, and there is an Islamic State where there was none before. Russian intervention in Syria, however, could be worse.

First, we (as in the United States) are a wealthier power, with far more people. We are more able to absorb the consequences of grave strategic errors. Second, in good part because of these grave strategic errors, the region in which Russia intervenes is far more volatile now than before. There are more weapons in circulation, weaker governments, more sectarian animosity and less trust in incompetent and authoritarian governments. Third, we also have an entirely different relationship to the Muslim world than Russia does.

We are, for one, very far away. We also do not have restive Muslim populations, fringe GOP fantasists aside. American Muslims identify as Americans. American Muslims are not the indigenous, dispossessed descendants of subjugated kingdoms, steamrolled in the building of an empire that forced them from their homes time and time again. Russian intervention in Syria could very quickly land that country in quicksand, while emboldening its separatists and secessionists at home, some of whom have already built links to extremist groups operating in Syria. The Economist even recently argued that Putin’s foreign adventures were not a sign of strength, but of desperation, and mapped out areas which might one day secede.

But Russian intervention wouldn’t just be bad for Russia. Russia has inserted itself into a conflict that appears so confusing as to be confused for interminable. More troops won’t fix the civil war. They may just make it that much worse, and that much more global. Which is, again, what ISIS wants.

Islam versus Islam

Many analysts of the present Muslim world claim that current crises can be understood as a kind of civil war, not of the directional, ‘North’ versus ‘South’ variety, but based on alliances. Countries fight against one another even as they fight their own populations. The conflicts are multi-sided, confusing, even overwhelming, and all the more difficult to untangle because they are, to a great degree, about competing interpretations over the same set of texts. Nor is this exclusive to the region.

Many Muslims I speak with are deeply, almost existentially, anguished about what they see happening in Syria and the wider region, about the tearing apart of Muslim-majority societies, the rise of groups which outdo al-Qaeda in violence, the continued victories of regressive dictatorships over nascent democracies and populist uprisings. I am sure, at their peak, Nazism and Communism might well have augured the end of a meaningfully human civilization, making it hard to see a better future. There is a reason 1984 was not written in 1984.

In times of negativity, people search for explanations for the darkness around them. Ineluctably, they begin to move from asking how to stop certain kinds of events from happening—because they begin to feel, like all wars of long duration, that these are inescapable and therefore are intended to be—and begin to wonder what they mean. If they cannot be stopped, perhaps they’re not meant to be stopped. (Which makes them that much harder to stop.)

Not long ago, one of the world’s leading Muslim scholars, Hamza Yusuf, born Mark Hanson, delivered a remarkable Friday prayer sermon which was widely viewed and discussed in Muslim communities, even as it was almost entirely overlooked in mainstream Western media. In it, Yusuf agreed that ISIS was a sign of the end times. Mining the same traditions ISIS does, except with skill and sophistication, Yusuf argued that the Islamic State’s role in our eschatology was rather different than what they claimed themselves to be. Not Caliphs, not righteous, not Islamic.

The dark side, if you will, of the Muslim force. Not on Jesus’ side, but on the other side. But that bears dwelling on. The conflict, in the Islamic tradition, will be between two men essentially claiming similar kinds of authority. Isn’t that the definition of an internecine struggle—when the same texts are taken to mutually exclusive conclusions?

Either you’re the Real Messiah, or you’re the False Messiah.

I remember, while growing up, how we used to read these very same prophecies and wonder what they meant. We were too naïve and too sheltered to realize that what was described was to be feared, not indulged; apocalyptic movies are entertainment, the apocalypse is not. We wondered, even doubted: Can this all really happen? Will this happen? What do end-times prophecies say about free will and determinism?

If God has to send Jesus to help us, does that mean He only infrequently intervenes in history? What then is the product of our efforts, and what is the product of His? How can we be morally accountable for our deeds if we have, as it might seem, so little choice in them? I brought a modern, American sensibility to Islam, too. What if end-times prophecies are self-fulfilling prophecies?

Anyone who has watched, and understood, the movie Minority Report, should be unfazed by such queries: What if something happens because the prophesying of its happening makes us make it happen; what if the cause is actually the effect? This is, I think, why Russian intervention in Syria scares me most. In Aslan’s cosmic war, there is neither ordinary victory nor recognizable defeat, but endless struggle.

If we are supposed to fight them at Dabiq, an ISIS commander might think, let us provoke them to fight us at Dabiq, since anyway that is what is supposed to happen. And if we do that, he will think, he will be advancing a narrative that advances his cause. He might provoke war, directly, with a nuclear power, in the belief that he is obliged to. If we were supposed to fight Crusaders, after all, and the Russians are here now, then they must be the Crusaders.

And so angry young Muslim men believe Putin’s foreign policy corresponds to ancient texts, while their Christian counterparts argue Iran and Russia represent Satanic forces. And thus are we led, inexorably and irresistibly, not by outward compulsion but by inward conviction, toward the same conclusion: a war that must not end until time itself does.