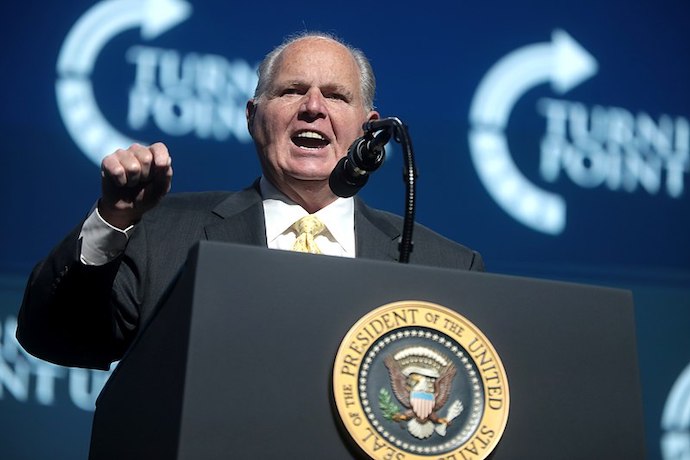

Rush Limbaugh was a persistent son-of-a-gun, by which I mean he persisted at being an evil, racist, bloody-minded drug addict and possible sex tourist. And no, I’m afraid that unlike similar charges lobbed at public figures, none of that is made up. News of Limbaugh’s death at age 70 on Feb. 17 led to a flood of such evaluations (for a while, Limbaugh was trending on Twitter alongside “Rot in hell” and “Good riddance”). It also prompted a lively online debate over the appropriate attitude to take when a controversial figure dies—and by “controversial” I mean, well, see above.

We might as well consider the question in some detail, given that the passing of at least one president will almost certainly be here before you know it. (Please note that I’m not wishing for anything—it’s just that he’s an old man with notably poor dietary and exercise practices. No one will be surprised is what I’m saying.)

As a formal matter, there’s no rule, exactly. At least one rabbi says Jews should have no trouble “speaking the truth about people who caused great harm.” The saying, of the dead speak no evil, itself was first recorded by the pagan philosopher Diogenes in the early 4th century, quoting a source nearly a millennium earlier, so it’s not a Christian teaching. I’m not familiar enough with other traditions to speak with any confidence, but I’ve never heard of such a prohibition in Islam, Hinduism or Buddhism. Most likely, it’s become a cultural norm in the West not to trash the dead because of Christianity’s general ambivalence about judgment, and a broad sense that we have better things to be doing.

But if you’ve learned nothing from reading Religion Dispatches, you should have learned that it always pays to interrogate the “we” when it comes to such matters. Limbaugh had a very long list of people and groups he’d been cruel to over the years—and he was very cruel. To Black Americans, by deriding the first Black president as “Barack the Magic Negro“; to immigrants whom he called the unassimilated “third world” invading the United States; to the LGBT community through his “AIDS Updates” celebrating the deaths of homosexuals; to Sandra Fluke whom he mocked as a “slut” and a “prostitute”; and to those on the wrong end of his untold thousands of other snide, bigoted comments. But Limbaugh’s many bigotries didn’t just harm his targets: they were and still are cruel to all Americans. They made his listeners and those forced to overhear him complicit in hate, diminished the collective sense of goodness, and gave generations of angry white men an excuse to abuse others, verbally, emotionally and physically.

In the end, as Jeff Sharlet astutely noted, Limbaugh was a forerunner and a microcosm of the contemporary Republican party, with its nihilistic horizons extended no further than “triggering the libs” by being as persistently, obnoxiously, offensive as possible.

There’s a straight line between Limbaugh’s radio shows and the turmoil and bloodshed of Donald John Trump’s time in office, just as there’s a line between between political correctness and cancel culture; between scoffing at the liberal media and QAnon; and between generalized white male rage at the loss of entitlement and white nationalism. If his victims want to take the opportunity of his death to vent, well, who can blame them? (The Gateway Pundit, for one.) More to the point, who can silence them? If anyone dared, I tell you the very stones would cry out with what a sleazebag he was! People can have their feelings, unseemly or not.

Still, there is a wretched irony in Limbaugh’s death coming on Ash Wednesday, when Christians are encouraged to consider their own sins and failings. That this, possibly the most judgmental man to walk the face of the earth in recent years, should pass away on the one day above all others when his co-religionists are heartily encouraged to refrain from judgment, is more than a little too rich. Which does not mean that Limbaugh gets a free pass. The Christian injunction against judgment gives no exemption from being held accountable for one’s misdeeds, even in death.

Christians hold back on judging others because we are taught that all—all—have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. You and I might be able to stand taller before God than Rush Limbaugh, but so can an ant over an aphid when viewed from the top of Mt. Everest. Point is, for Christians nobody gets to heaven on their own, and you might not want to blow your shot at getting some help by looking down on somebody else, living or dead, objectively awful human being or not. This is one of the screwiest teachings in the Christian canon, and believing it makes us terrible buzzkills.

I have the privilege to believe it, and that’s exactly what it is: a privilege. I and people like me—white, Christian, middle-class, cishet—have the privilege to believe that even strident evaluation of a legacy is one thing, but that it robs one’s own humanity to revel in the death of another. It’s also a privilege to be able to say with a shrug “He’s just not worth my hate.” Limbaugh’s victims may be able to claim such a privilege for themselves, or perhaps not, and no shame on them if they can’t help letting out an expletive or three when they recount his many trespasses, against them, against fairness, charity and common human decency.

That might be the ultimate judgment against Limbaugh, that he has died, but the people he hated live on to fight against his memory every day. It might be fairly objected that that’s exactly what he’d want, but then every devil chooses his own hell, as Milton tells us in describing Satan falling from the sky. Speak evil, speak no evil, whatever. Just be free, and grateful that you’re still alive to have the choice.