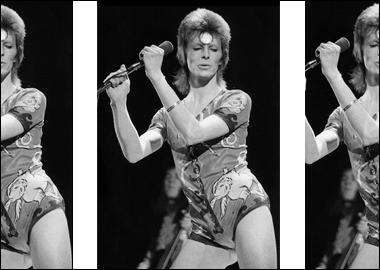

In this next installment of Mark Dery’s personal essay-cum-cultural critique, the author, stranded in 1974 suburbia at the age of 14, has his born-again Christian brain short-circuited by the gender-bent but heart-stoppingly beautiful Ziggy. Read the first installment here, or better yet, never miss another feature by signing up for the RD Daily Newsletter here. You’ll receive our features and blogs every day in your inbox.

•

CHARING CROSS STATION, London, 9:10 P.M:

And when he arrived they screamed and they cried, and they rushed, and gushed forth and beat their feverish feminine fists into the backs of the indeed brave coppers who shielded HIM. For he is indeed HIM.

One girl, her face bloated, and most ugly with tears and ruddy emotion, fell half-way twixt train and rail. A young copper dragged her to safety. Ten yards down the platform HE was pretty close to injury to HIM. Bowie, despite all the fierce bodyguarding, was being kissed, and pinched, and touched, and ripped at. His hair now untidy; his eyes wild; his mouth open. A picture of terror. But his open mouth also bore the shadow of a crazed smile. They pushed him against a carriage door. It took Spartan constabulary to lift this small squirrel-haired figure to safety; his face now very creased with every emotion a face could ever squeeze itself into. And they squeezed him into a car that was battered, and clawed at. And that car squeezed its way to safety. And Mr. Bowie was back in England. And on Platform One, in a dirty wet huddle, lay two plumpish girlies, crying, and holding each other, and just crying. Everyone had gone, except them. Their tights all ripped, their knickers showing. And they just lay there crying.

—Roy Hollingworth, “Cha…cha…cha…changes: A journey with Aladdin,” Melody Maker, May 12, 1973

Crowd:

Will you touch, will you mend me Christ?

Won’t you touch, will you heal me Christ? Will you kiss, you can cure me Christ?

Won’t you kiss, won’t you pay me Christ?

Jesus:

Oh, there’s too many of you, don’t push me Oh, there’s too little of me, don’t crowd me Heal yourselves!

—“The Temple,” Jesus Christ Superstar (1970)•

On July 3rd, 1973, Bowie ceremonially retired his Ziggy Stardust persona before a crowd of true believers, a melodramatic gesture immortalized in the D.A. Pennebaker documentary Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture.

Actually, it was more ritual sacrifice than retirement: Bowie sentenced Ziggy to death, partly because the leper messiah’s shock value was losing its jolt, partly because the strain of playing the Jesus of Cool, onstage and off, was beginning to tell on him. “It was quite easy to become obsessed night and day with the character,” he later recalled. “Everybody was convincing me that I was a messiah…”

Returning for an encore, Bowie leans into the mic with a knowing, almost coy smile. “Of all the shows on this tour, this particular show will remain with us the longest because not only is it the last show of the tour, but”—pause for dramatic effect—“it’s the last show that we’ll ever do.” A collective gasp from the stunned crowd, intermingled with stricken cries of “No!” On cue, pianist Mike Garson pulses the opening chords of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide”: “Time takes a cigarette/ puts it in your mouth…”

Ziggy was our savior. He rescued my only friend Lisa and [me] (two American kids with very British taste in music) from teenage boredom and launched us through outer space to his very own planet, somewhere beyond Pluto. The U.S. TV show [Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert] featured the final Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars concert at London’s Hammersmith Odeon. It was the first and only time we would see Ziggy live in action (besides the hundreds of magazine photos and posters we had). The stage was dark, the focus was soft, and the camerawork shaky and evasive. Ziggy was shrouded in mystery. He was definitely from the cosmos; androgynous, surreal and seductive, perfect porcelain skin, unearthly mismatched eyes with a foreign, piercing stare. […] We saw this on a black & white TV, yet it was still utterly compelling. We had found our ultimate icon, and there he was announcing his final performance. Our devastation mounted.

—Madeline, a Bowie fan

Late on the night of October 25, 1974 in a San Diego suburb hard by the Mexican border, a 14-year-old me kneels close to the TV, flicker bathing my rapt face. It’s the only light in the house. I’m watching Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture, D.A. Pennebaker’s 1973 film of Bowie’s farewell performance as Ziggy, on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert—the same broadcast that’s saving the bored teenage souls of Madeline and her friend Lisa, somewhere in New York.

Down the hall, my parents are asleep. It’s past midnight, and I know, somehow, that I’m the only kid in my chicken-coop suburb beholding this miraculous visitation, wondrous as the presentation of the hermaphrodite in Fellini’s Satyricon. To be sure, Bowie’s a freak—code for “fag” among the real-life Jeff Spicolis in my junior high class, righteous dudes whose idea of total radness is firing up a beer bong, dropping the needle on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, and watching The Wizard of Oz with the sound turned off.

But he’s so heart-stoppingly beautiful, in such a confusingly feminine way, that he short-circuits my teenage brain, a brain whose congenital straightness I’ve never questioned…until now. Those Venus de Milo shoulders; that slim-hipped teenage-boy torso on top of those Rockette legs; that otherworldly face—moon-white, immaculate, like Dietrich in cryo-sleep. And the way he moves: biker-butch one minute, swivel-hipped the next, with a predatory grace true to Ziggy’s boast in “Hang on to Yourself” that he and the Spiders “move around like tigers on Vaseline.” “Come on, come on,” he pants, in time, syncopating the Spiders’ skidding, careening beat. I catch myself thinking how sexy he is. And I wonder what that means. And I realize I don’t care.

•

Riding the volume knob, I split the difference between waking my parents and coaxing all the ecstasy I can from the TV’s tin-can speaker.

I don’t know how to take this

I don’t see why he moves me

He’s a man

He’s just a manShould I bring him down

Should I scream and shout

Should I speak of love

Let my feelings out?

I never thought I’d come to this

What’s it all about?—Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” Jesus Christ Superstar

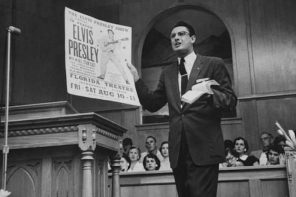

Earlier that night, I’d gone looking for another sort of ecstasy. Crowded into the House of Abba with the other Jesus Freaks, I prayed with eyes closed and palms uplifted, whispering sweet nothings in God’s ear, beseeching him to fill me with his holy spirit.

Part 3: In The House of Abba, a Friday night coffee house church that scrapped the liturgy and smudged the historically sharp line between congregation and clergy, our teenage narrator finds Jesus Christ Superstar and discovers a Christianity that rocks.