The slogan “Islam is a religion of peace” has always sounded off key to me.

It’s not that I think the statement is false. In fact, my experience working in the American Muslim community resoundingly affirms that peace is the heart of what Islam means to its adherents, who revere and respect their tradition’s calls for justice and righteousness. But in the U.S. context, saying the words “Islam is a religion of peace” does little to help bridge the gap between Muslims who believe their faith compels them to do good in the world and non-Muslim Americans who had little knowledge of Islam before September 11, 2001.

The gap is intentionally widened by the concerted efforts of a cluster of intensely anti-Muslim and anti-Islam individuals and groups seeking to depict violence done in the name of the religion as the norm rather than a fringe movement. In doing so, this short phrase is openly mocked on Fox News and in other right-wing news media. Those who avow the truth of those words often find them thrown back in their faces whenever there is an act of terrorism committed by someone claiming Islam as their religion.

So I’ve come to ignore these words. In fact, I even roll my eyes when anyone—naively, in my opinion—imagines it might somehow be useful to intone them yet again.

But then I went to Amman, Jordan.

I was there to participate in a convening of youth leaders from Africa and the Middle East under the auspices of the United States Institute of Peace, which had invited me participate in the meeting and to lead a training session on conflict communication. As we sat around a table in a hotel conference room, I was astounded by the stories of young community leaders doing work to change their neighborhoods and their countries against a backdrop of poverty, violence and turmoil. And I met Ndugwa Hassan, one of these young leaders.

During a break from the conference sessions, he found table at the end of the room and laid out materials from his organization, the Ugandan Muslim Youth Development Forum (UMYDF). I walked over and was immediately struck by the pictures in the upper left corner of the table. Ndugwa was shown sitting on a bed, his clothes covered in blood. He was bleeding from his face. I asked him what happened, and he described the injuries he sustained on July 11, 2010 at the Kyadondo Rugby Club in Kampala, Uganda.

He and his friends had gone to the club to watch the World Cup final between Holland and Spain. Then an al-Shabaab cell launched the organization’s first terrorist attack outside of Somalia. Two blasts were set off, one in front of the screen where the match was being broadcast. Ndugwa and his friends felt the blasts. Injured, but not mortally so, they ran to the nearest hospital. He explained what took place in the aftermath:

When I left hospital the following day, I watched the news. The attack had claimed over 80 lives and left 76 injured. Investigations were underway, and later suspects were paraded for trial. All suspects and accomplices were Muslim youth. I was so puzzled and asked myself so many questions. Why would people believe that when you kill someone you get a passport to heaven? Why would a young person be lured into acts of terrorism? Why does a 17-year old boy in a tough neighborhood join a gang? Why does a high school student in a quiet town sign on to terrorism groups who preach supremacy? Why does a young woman abandon her family and future and become a suicide bomber?

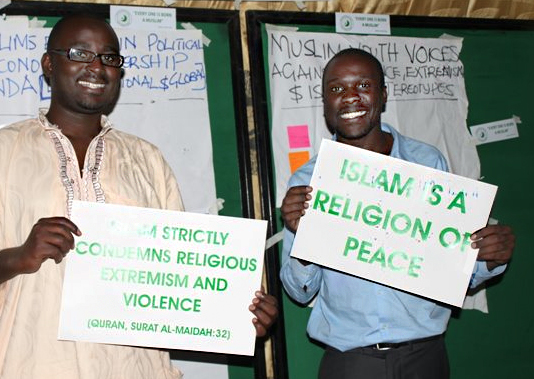

In the months that followed, Ndugwa and a friend who was with him that night in the stadium founded the UMYDF. He has been involved in trying to fight the lure of terrorist groups with what he describes as the true teachings of Islam. They work with imams to turn mosques into youth development centers where those who are at risk of being drawn into potential violence are counseled, given educational services and vocational training. Other UMYDF publications on the table in our conference room detailed the group’s activities. And at the lower right of the display was a simple green and white bumper sticker that read: ISLAM IS A RELIGION OF PEACE.

I experienced those words in a whole new way. Ndugwa was not using that slogan to try to explain his religion to a non-Muslim American audience across the yawning cognitive divide that opened between the communities after 9/11. Instead, he and UMYDF were trying to teach Muslim youth in Uganda—many who are as young as 12 when they are lured into violence—to see their religion in a different way.

It’s not a slogan explaining Islam to me as an outsider, but rather a slogan encouraging young Muslims interpret their sacred tradition in a way that is positive and life-affirming—an especially urgent task in places where there are people trying to convince young Muslims that Islam is calling them to violence.

And it is only one tool of UMYDF, which has a complex and sophisticated understanding of the multiple drivers of youth violence. Ndugwa explains the importance of listening to youth, who are “actors with compelling stories and motivating factors that are important to understand, so that we can begin to craft policy solutions to problems too often ignored or treated reductively by the policy community as simply religious, tribal or cultural.”

Read as part of a larger in-house movement to reassert the soul of Islam and push back against the forces of extremism, this bumper sticker had new meaning for me. And I realized that I had cynically underestimated its power.