The Bible and the People

By Lori Anne Ferrell

(Yale University Press, 2008)

It is a commonplace, in the congregations and in the culture, to refer to “the Bible,” with very little reflection on what we actually have in mind. “The Bible says”… “the Bible teaches”… “the Bible shows”… these are quite common ways to ground arguments about a wide range of moral and political and theological issues among Christians in the United States today.

The shortcomings of such a perspective are evident once we stop to think about it. The Bible, after all (by which I mean the Christian Bible) is an eclectic combination of many books produced over an enormous span of time and an enormous geographical range. It is constituted by 39 books written primarily in Hebrew, and a number of those books (notably the Psalms and Proverbs) might be further subdivided into the poems and pithy aphorisms they contain. Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians include a few more books in their Old Testaments than the Protestants do.

Then, of course, the Christian Bible also includes 27 books all written considerably later, in the Greek language and over the span of little more than a generation (somewhere between 70 and 110 CE). All this to say that figuring out “what the Bible says” on any given topic is difficult and sometimes well-nigh impossible.

Taking the Bible seriously means first taking its own history seriously, and then taking what it says seriously enough to admit the density and opacity of some of its pronouncements. “Mystery” is a word that appears with some regularity in many biblical books.

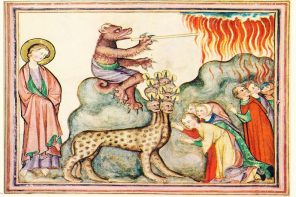

In addition to these primarily historical questions, there is another matter worthy of careful consideration when we endeavor to speak in general terms about the Bible. What kind of a book do we imagine when we speak of “the Bible”? Presumably we do not think of the long papyrus scrolls that constituted the original “books” in the Hebrew Bible. And we probably do not think of the richly-illuminated handwritten and leather-bound codices that early Christians began producing not long after the New Testament writings had been completed.

No, we are far more likely to think of the modern Bibles we know, identical books printed in massive print runs, replete with all sorts of readerly helps, from running headers at the top of the page to chapter and verse numbers below. Imagine that: the common Protestant practice of “proof-texting” (citing one verse as a way to capture the essence of biblical truth) would have been impossible before the advent of the printing press, when Bibles first began to have section breaks, chapters, and verses (none of this earlier than 1560). Prior to that, people did not speak of verses; they spoke of stories. And the Bible is chock full of stories.

The 20th Century, “Uncannily Akin” to the 16th?

To be sure, finding new ways to talk about books as books is hard enough; to communicate that new way of seeing in book form is harder still. In The Bible and the People, Lori Anne Ferrell does just that, telling the story of all the most precious Bibles in the possession of California’s Huntington Library (for whom she was curator of a 2003 museum exhibition). But this book also offers a luxurious visual walking tour through the manifold ways in which Bible-books are made, and how the people who make them also make them meaningful.

Dancing between texts as diverse as the gloriously illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels, to the resplendent mechanical artistry of the Gutenberg Bible, and on to more demotic forms such as the red-letter King James pocket Bible or the dizzying bric-a-brac of the 66-volume Kitto Bible, Ferrell never fails to communicate her contagious delight in the written word. But she is more than a reader of tremendous subtlety and sensitivity, more than a mere bibliophile, and far more than a writer capable of uncanny lyricism herself. She is an historian, first and last.

The central contention of The Bible and the People is that the Modern period is subtly defined by a vast array of biblically-inspired religious questions. The Modern period is literally bookended by the Protestant Reformation on one side and the period of whatever-we-are-living-through-now on the other. Call it Late Modernity, call it Hyper-Modernity, call it Post-Modernity, call it the Electronic Age.

The dizzying velocity of change in social institutions and communications technology, in fact, can make the twentieth century seem uncannily akin to the sixteenth in many ways: here, as then, new translations again paved the way for other, more material, forms of scriptural refashioning.

That is the central thesis of this important book. The question implicit in that thesis is this: What will become of the Book, and of the Christian religion, in our time?

Answering that question requires the skills of a masterful historian, religious fluency, and a humane wisdom borne of compassion and empathy. These are the sources of the remarkably sure guidance Ferrell provides.

Radical Act of Translation

If the Modern story really begins with the Reformation, then this has a great deal to do with renewed arguments about the Bible as the Book. In a long chapter entitled “The Politics of Translation,” Ferrell walks us through the complex and bedeviled history of a truly Modern English-language Bible.

We all know how Martin Luther’s revolutionary reform of the Catholic church was embedded in two fundamental practices: translation of the Bible into the German vernacular, and thus putting the Book back into the People’s hands. That dangerous and unsettling principle, “the priesthood of all believers,” requires first and foremost a Bible this vast priesthood can actually read. So the political act of translation was a conscious attempt on Luther’s part to break the stranglehold that Saint Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, the Vulgate, had over medieval people and the medieval church. The decision to translate the Bible, then, was an act of liberation for some, and an act of treason for others.

Especially in England, where Henry VIII’s departure from the Roman fold had at least as much to do with politics and multiple marriages as it did with theology. Indeed, England arguably became the most fascinating place to observe “the politics of translation,” precisely because in England everyone understood the political stakes. There was, after all, a national church in the offing. This is why William Tyndale (1494—1536) was executed for his English translation of the Old and New Testaments; in short, they were unauthorized.

Other scholars had already had a crack at the anti-ecclesial art of Bible translation. Followers of John Wycliffe (1330—1384) had already produced an English language Bible at Oxford, as a way to push for reforms of ecclesiastical hierarchy and practice. (To this day, the Wycliffe Society is engaged in an impressive effort to translate the Bible into every language currently spoken on Planet Earth). So clearly, the Reformation had been in the offing for a very long time.

Tyndale was forced to publish his Book overseas, and the printing houses he used often did so under pseudonyms. He finally met his end after fifteen months’ imprisonment in Belgium. And yet ironically, Tyndale’s assistant, Miles Coverdale (1488—1568), managed to profit from what had cost Tyndale his life. Coverdale published his English language Bible in 1535 and, by 1537, it was being printed openly in London. When Henry VIII realized that his national church needed a national Bible, he selected Coverdale’s version as his “Great Bible.” Edward VI then commissioned the Book of Common Prayer in 1549. Both books were ordered to be purchased by every church in the land.

And since “Reformation requires transformation of doctrine, sacramental practices, and methods of worship,” it was “the new Prayer Book—not the Great Bible—[t]hat finally made the Church of England English.”

Now, we all know the main outlines of what came next: fully a century of religious and political mayhem—civil wars, executed kings, protectorates, restorations. But it would be too simple to say that Protestants were for vernacular translation, and Catholics were opposed to it. Not at all, Ferrell reminds us. Exiled English Catholics produced their own English language Bible in Douai, France in 1582.

It would also be too easy to say that Protestantism remained a singular movement. Rather, the Protestants multiplied their versions of the Bible almost as rapidly as they multiplied sects and doctrines. During the brief return of Catholicism under Mary I (a.k.a. “Bloody Mary”), a Protestant firebrand named William Whittingham (1524—1579) fled to the Continent, settling finally in Geneva, home of the hardest of hardcore Calvinism. He produced a new English Bible in Geneva in 1557, the so-called Geneva Bible, similar to Tyndale’s in its way, but full of marginal commentary confirming his firmly-held predestinarian theology. This was likely the Bible that Shakespeare knew.

When Elizabeth I came to the English throne the next year, no one could have predicted that she would settle England’s religious identity, simply because she would rule for so very long (her elaborate system of secret police might have had something to do with this as well). The national Church of England was her great legacy; England would not be Catholic again. But of course that did not spell the end of religious conflict on the Emerald Isle.

Rather, the security of the Protestant establishment created a world in which Protestants could now argue more freely with one another. One purist sect, the “Puritans,” complained of the laxity of their quasi-Protestant brethren, and their less than pure theologies. A great many English language Bibles proliferated under Queen Elizabeth, and since every translation is also partly an interpretation, they presented subtly and not-so-subtly different theologies as well.

My favorite example comes from the Puritan scholar William Fulke (1538-1589), who published a comparative New Testament in 1589, one in which the Catholic Douai Bible and the so-called “Bishop’s Bible” of 1568 were printed in parallel columns. In the lyrical prologue to John’s gospel, according to the Catholics, “In the beginning was the WORD, and the WORD was with God, and God was the WORD.” It is notable that the Catholics capitalize WORD, but not God. It is also notable that they refer to “that WORD” consistently as “he.” The Anglican bishops refuse to capitalize any letter of “word,” and they refer to that divine word consistently as “it.”

These are not trifles, not back then anyway. They had everything to do with what language best captured the central mysteries of the faith: “a threefold Divinity which nonetheless was to be accounted as an indivisible Singularity,” most of all.

A Translation Around Every Corner

One year after James I ascended to the English throne, he commissioned a new English translation of the Bible, to be created by a committee of biblical scholars working both from the original languages as well as all the prior English language editions then available. Now the peacemaking quality of this gesture seems evident. James wanted a Bible that everyone in England could live with. But the truth lay elsewhere: James wanted a Bible that would work against the continued influence of Catholics and Puritans alike.

This is a stunning historical fact: the noble “King James Bible” is an anti-Puritan Bible, and its very lyricism was designed for liturgical use, not private reading (of which the King was suspicious). Finally, to call this Bible the “Authorized Version,” as is commonly done, is a bit of a misnomer: “it was never actually ‘authorized’ but only ‘appointed to be read,’” Ferrell reminds us; “to this day, the only truly ‘authorized’ English Bible remains Henry VIII’s.”

Now let us jump ahead to the quotation with which I began, the one linking the 20th (and 21st) century to the 16th. For a variety of reasons, the English Bible commissioned by James I was by far the most popular Bible in the British colonies in the New World (and when the War of Independence broke out, English Bibles became a very difficult commodity to obtain). King James’ version remained the Bible of choice, by and large, until the late 19th century, when the English Revised Version (ERV), the “first significant revision of the English Bible since 1611,” was published by Oxford University Press in 1881. This announced what became virtually a second wave of translation-and-reform, symbolized best by Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Woman’s Bible, published in 1898.

The ERV was not popular in England, and across the Atlantic it fared little better; all it accomplished here was to make its readers mindful of the need for a truly Americanized Bible. The American Revised Version was finally published in 1901, yet it was no more popular in the New World than the ERV was in the Old.

In 1947, the Revised Standard Version (RSV) met with greater success. And here is the remarkable thing: the publication of the RSV is what finally generated a reaction that is an important part of the religious landscape in the United States today—“the King James Only” churches.

Such KJVO churches lie on opposite ends of the theological spectrum: high church Episcopalians retain the KJV because it fits well with the Book of Common Prayer still in liturgical use; and fundamentalist, mostly independent Baptist churches retain the KJV as the only truly inspired word of God. In its extreme form, KJVO Baptists argue that the divine spirit breathed through Wycliffe and Tyndale (but not Douai) and culminated in the foreordained event of the 1611 “Authorized” English Bible. A strange conclusion to draw about an anti-Calvinist Bible.

For those who were not tempted by the Episcopalian or fundamentalist options, the need for new English Bibles continued to be felt. Now they are legion: the New International Version (NIV) was published in 1978, the New King James Version (NKJV) in 1979, the New Jerusalem Bible (NJV) in 1985, and the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) in 1989. There is even a periodical version published in the teen magazines, “Revolve” and “Refuel,” called the New Century Bible (NCV), a version popular among evangelical publishing houses and intended to translate “thought for thought rather than word for word,” keeping an originally simple message simple, direct and clear, “as God intended it.”

And on it goes. Translations, unlike canons, are never closed.

What Will Become of the Book in Our Time?

Like no other book known to me, Lori Anne Ferrell’s self-described “cultural history of the Bible” reminds us with an attractive combination of visual artistry and rhetorical bravado that everything is historical: the Christian religion, the Christian book, the Christian people. That Ferrell brings what she calls the “mutual attraction” between a people and a book to life (in point of fact, as she tells it, it is the story of a love affair) is perhaps her greatest achievement. There are a great many books about books, but by emphasizing the symbiosis that brings people and texts into subtle spiritual alignment, Ferrell brings the lives and loves of the Bible’s countless makers, and readers, before us with poignancy and grace.

This book succeeds because its author possesses two talents rarely found in the same person. She is as rich a reader of images as she is of printed words. As a profound admirer of Puritan prose, Ferrell captures the power of rhetorical expression and translational virtuosity as few others can. Words are one large part of the way people communicate meaning with power. And the Bible is a collection of writings with a unique power to move.

As a profound student of the Protestant Reformation, Ferrell attends to the power of images as only someone who works within an iconoclastic tradition can. Images are another way people communicate meaning with power. And the Bible had been produced with such loving care and attention that it has virtually become an icon itself.

The Bible and the People offers an unforgettable history of a Book that refuses to be forgotten. So what will become of the Book in our time? And what does the Bible say? Ah, sweet Horatio, more than is dreamt of in all our philosophies.