I begin my debut column for Religion Dispatches with a confession of failure.

Recently an editor of a daily newspaper with national circulation asked me to write an opinion piece on the role of evangelicals in the 2008 election. Also, he wondered, could I recommend somebody who’d be willing to opine on Hispanics and religion (and the election, of course. Always the election).

I’d like to be able to report that I laughed and said such subjects were impossibly broad. Instead, I answered, “Me? Why, certainly!” I imagined I could use an op-ed page to undermine the banal tyranny of op-ed pages. I thought I could game the press. Communists used to call what I had in mind “boring from within,” and they were more accurate than they knew.

What led me astray? I’ve been throwing darts at the press in my capacity as editor of The Revealer, published by New York University’s Center for Religion and Media, for several years, and I’ve been participating in the very endeavor of which I’m skeptical—mainstream media documentation of religious life—as a contributor to magazines such as Harper’s and Rolling Stone, and as an occasional talking head for newsier venues. In other words, I’ve been playing both sides, critic and participant in the church of the press.

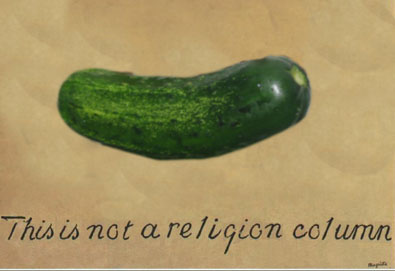

But the opinion pages of a major daily are different. They purport to be above “sides.” They’re the chief forum for the manufacture not of consent, exactly, but of conventional wisdom, the best ideas of some genuinely thoughtful people commingling with the worst ideas of some genuinely calculating people, all of it boiled and reduced to a paste of anecdote and “reasonable argument,” with perhaps a clever turn of phrase on the side. Like a pickle.

Don’t get me wrong—I love junk food, and I read opinion pages. I just don’t know how to write for them. I suggested to the editor that no such creature as a “Hispanic religious vote” really exists, that at the very least American Hispanics are divided between Catholicism, evangelicalism, and Pentecostalism, not to mention those who are simply irreligious or call themselves “spiritual but not religious.” Many Hispanic believers straddle two or more of these categories. Each of these strands has conservative and progressive and even radical branches, some shaped by local traditions or the quirks of a heretic who functions as a hinge between one belief and the next. Consider Chimayo, New Mexico one of the most popular Catholic tourist sites in the United States, beloved for a soft little patch of ground from which blessed soil can be drawn to heal whatever ails you. This belief was borrowed from the Native Americans who preceded the Spanish priests who claimed to first make this discovery, and it’s maintained by a priest who trucks in 25 tons of garden-variety dirt a year to keep the sweet spot forever full of magic earth. Quick—who’s he voting for?

The editor would have none of that. “I am looking,” he wrote, “for someone to say: this is the religious vote of the future.” (If there is someone out there willing to say that, contact me and I’ll send your name along. Let’s get your career jump-started!)

My own dreams of punditry went no further than my next reply. The most I could say on my assigned topic, I wrote, was that Christian conservatism is neither dead, as widely reported by the secular press, nor becoming more “moderate.” Rather, many strands of Christian conservative thinking are broadening to encompass concerns long relegated to the back burner. This broadening makes the vision no less conservative, but rather differently conservative. It is, however, less predictable, less partisan, and in the terms of discussion allowed by establishment media, that makes it less influential. That may well be true according to the narratives of campaign strategists, but the loss of influence at the ballot box could easily translate into a greater influence on what evangelical intellectuals are fond of calling “the culture,” by which they mean a concept of the public sphere from which they feel excluded. They recognize that any American sphere that doesn’t include them is a rather small bubble, indeed. The bullies among them want to muscle in and take it over. The most interesting activists among them want to pop it.

So how do we measure their influence? I have no idea. In the establishment press, you’re free to reject conventional wisdom if you have a new paradigm to propose. I don’t. My proposal is more modest: an end to paradigms. Instead, let’s gather data. Not survey responses but stories, the kind that don’t necessarily have morals, that don’t always come to a “point.” Just like this first column for Religion Dispatches, a manifesto for messiness in writing about religion, politics, and media. Journalists, editors, scholars, my comrades on the God beat: Please, don’t tidy up the narrative of religion in America to conform to the demands of election season op-ed pages. Reveal it for what you, better than any individual believer or unbeliever, know it to be: wildly pluralistic, profoundly unstable, ingeniously conformist, weird, funny, tender, banal, and infused with wit, gloriously difficult to define.

Care to comment? Send a Letter to the Editor at: submissions@religiondispatches.org