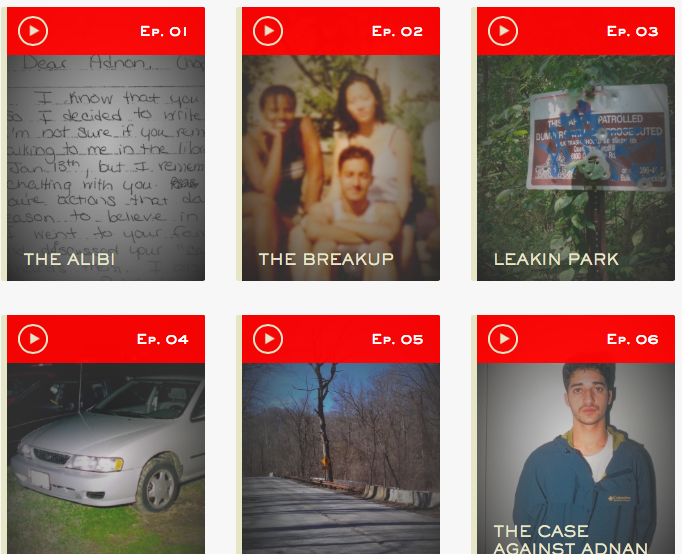

In the three months since its premier, Serial has become the most popular podcast in the world—the fastest to reach 5 million downloads in iTunes history. Serial blends True Crime thriller with investigative journalism, teasing apart issues of religion, race, and romance in a 1999 Baltimore murder case that put 17-year-old Adnan Syed behind bars for the murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee.

Was Adnan Syed falsely accused and a victim of bigotry? Is he a psychopath who manipulated Sarah Koenig and a Muslim community to support his story? Did Jay do it? What’s a Mail Kimp??

The final episode of Serial was released on Thursday, the 18th of December, RD’s Andrew Aghapour and Hussein Rashid live-tweeted the finale using the hashtag #RDSerial (see feed in sidebar). Below are their concluding comments from before and after, including some provocative tweets.

Note: spoilers below!

+++

HR: Two weeks ago, I did a piece on Serial talking about changing perceptions of Muslims in America. The episode that aired the next day blew my premise out of the water. Islamophobia was a huge part of Adnan’s trial. At the same time, the prosecution did use a construction of Islam that placed him outside of the fold of believers. Essentially, the prosecution became Chief Theological Officer of Islam, Inc., and showed how little they knew about religion.

AAA: I enjoyed your piece, and I wouldn’t say that episode 10 ‘blew it out of the water.’ There is indeed something striking, from a post-9/11 perspective, about the prosecution’s depiction of Adnan’s Islamic faith. Many of the anti-Islamic tropes that Sarah Koenig reports are indeed familiar: many believed that Adnan, as a Muslim, was more likely to kill an ex-girlfriend; at the bail hearing, prosecutor Vicki Wash (citing only one precedent in U.S. legal history) warned that Adnan would likely flee to Pakistan; and the State’s direct examination of Yaser Ali, in which a teenage friend of Adnan’s testified about how “Islam”—monolithically conceived—punished premarital sex.

These are just three examples of how Adnan’s Muslim faith and Pakistani dual-citizenship were used to cast doubt on his otherwise strong character. In the words of Rabia Chaudry in this excellent blog post, “it probably was not bigotry that brought the cops to Adnan’s door, but bigotry helped convict him.”

Yet—to affirm your recent insight, Hussein—there is an interesting contrast here from our post-9/11 perspective. The prejudice documented in Serial has a vintage to it: it’s classic 1990s Not Without My Daughter trepidation, the fear that Westernized Muslims harbor secret, ancient predilections towards violence and misogyny. Speaking now, over a decade after 9/11, this trope hasn’t disappeared but it’s certainly been displaced by an unabashed distrust towards outwardly observant Muslims.

I’d like to put the ball back in your court, Hussein, and ask for your response to the memo written by that “cultural consultant,” (below, right), courtesy of Rabia Chaudry. For me this is the most disturbing aspect of the whole case. A prejudiced jury is one thing, but this… as you’ll see, it’s something else entirely.

HR: That cultural consultant strikes me as being a bit trippy. It’s well before Wikipedia came into existence, but the content is very encyclopedia like. Even by 1999, no one with an advanced degree in the Study of Religion was talking about Islam this way. The work reads like a witness for hire.

I also find it really odd that we can’t know who this person is. I’ve done a few court cases, and anytime my work is used, I’m told my name will go into the record because it’s evidence, and the source is important. Really bizarre.

Listening to the podcast, I’m thinking more and more race and religion intersect in really interesting ways. Don is as likely a suspect as Adnan in the beginning. Yet, he’s not really part of the investigation so far, and I have to believe Sarah is reflecting the actual police work.

White people are automatically excused and believed, and every stereotype could be thrown at Adnan, and made-up information is easily admissible. There’s an interesting article over at Gawker about race and the criminal justice system at this time.

And it seems like the prosecutor really didn’t like Adnan, based on the opinion of this law professor.

+++

AAA: That was a wonderful conversation! I’d like to summarize with the help of a few tweets from our #RDSerial participants. First, I was struck by two related tweets by Brandon Bayne and Stephanie Gaskill:

One theory says Adnan is the thug (in 19th C./British colonial sense) and the other is that Jay’s the thug (21st C. America) #rdserial

— Brandon Bayne (@brandonbayne) December 18, 2014

@AndrewAghapour Convictions are often obtained by appealing to prejudice (implicit or explicit), not through physical evidence. — Stephanie Gaskill (@srgaskil) December 18, 2014

All of our participants agreed that the evidence leveled against Adnan was not sufficient to convict him, regardless of whether he is guilty or innocent. Serial’s investigation makes it clear that Adnan’s guilt was not established based on physical evidence; rather, he lost out in a competitive tale of two monsters. “Which is more believable,” the jury was asked, “that Jay is is a monstrous liar, or that Adnan has always harbored violence and misogyny beneath his friendly exterior?” There can be no doubt that Adnan’s faith, community, and citizenship played a significant role in this narrative.

Second, some tweets about Serial as a whole and the question of endings:

“Like trying to plot the coordinates of someone’s dream.” Prelude to the lack of an ending? #RDSerial #Serial

— Andrew Aghapour (@AndrewAghapour) December 18, 2014

Listening to #serial with #RDSerial and @AndrewAghapour…I am afraid that the ending will be a non-ending — Kyla Taylor (@Kyla_Taylor) December 18, 2014

Kyla Taylor and I were not the only ones—Serial fans have been obsessing over the finale ever since the podcast caught up with real time at around Episode 9. Fans wanted a neat and tidy ending, and the fact that we held it to an impossible Hollywood standard speaks to the podcast’s masterful narration. Adnan, Jay, Hae, and Gutierrez were compelling characters, but their stories were also dense and cluttered. Serial unpacked the case for us, creating a detective story in progress where listeners were fellow sleuths.

But in real life there are cases that just can’t be cracked.

Episode 12 couldn’t offer an “ultimate truth” moment, in fact Serial warns us against our hunger for final truths because this is what rushed Adnan to jail in the first place. (Once again, this was a failure of the justice system whether he’s guilty or innocent.)

Finally, I want to bring up a common critique of Serial: that Sarah Koenig and company were insufficiently attentive to various social issues, including religion and ethnicity. As an Iranian-American who was also a Muslim teenager in the ’90s, I join Serial’s critics in thinking that there are elements of race and religion that the podcast missed. But I also think that Serial should actually be credited here for making a critical conversation possible.

Serial dove into a messy and contentious issue and told the participants’ stories, often in their own voices, all the while pivoting around a journalist who refused to give herself the authority of a master narrator. Serial’s journalistic approach has created a space where critics, advocates, and participants can collectively make sense of Hae Min Lee’s tragic death and the events that followed.