This past Sunday night, a televised performance had a vast crowd singing along to Chris Tomlin’s “How Great Is Our God” and waving their arms back and forth along with a gospel choir. You might have thought you had accidentally switched channels to a megachurch service, but it was indeed the 2017 Grammys.

Chance the Rapper, triumphant from his three Grammy wins (including Best Rap Album), cavorted around the stage with gospel stars Kirk Franklin and Tamela Mann as they unabashedly praised God.

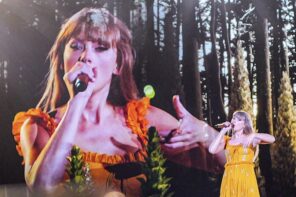

The display was only bested by a pregnant Beyonce’s gilded set—in which she performed “Sandcastles” and “Love Drought” decked out in an ornate ensemble that could only be an homage to Oshun, the West African deity that was heavily referenced in her remarkable visual album, “Lemonade.”

These epic performances were a culmination of the mainstream recognition that has been building for these artists and is further proof of what RD writer Alana Massey has called “Christianity hiding in plain sight” within American pop culture.

On Sunday night, the rest of America found out what many young Christians, especially Christians of color and queer Christians, already knew: “losing our religion” has allowed many of us to find it again, away from hallowed halls and stained glass. Having seen both Beyoncé and Chance in concert in the past year, I didn’t find their Grammy performances to be a surprise. I had idolized these folks for years, and now Chance and Bey are reaching their relative pop culture heights—and they’re doing it through the invocation of black divinity.

My summer days and nights were punctuated by Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and Chance’s “Coloring Book.” I liked the albums not only for their lyricism and rhythm but also for their exaltation of blackness; “Lemonade” as a meditative ode to black womanhood and “Coloring Book” as a carefree expression of black boy joy.

When I listen to these albums, it feels like church, it feels like home.

As a young Catholic who has had an increasingly fraught relationship with the institutions that informed her spiritual upbringing, this type of connection is meaningful, and I didn’t realize how hungry I had been for it until I found myself also belting out “How Great Is Our God”—something I hadn’t done with feeling since high school youth group.

It reminded me that in order to return, you first need to leave. Chance’s confession of “I used to hide from God, ducked down in the slums like shhh” was me as well as countless other Christian millennials who can no longer reconcile the god of their churches with the one working in their lives.

At a time when the inherent value of black lives is something being fought for in our country’s streets and courts, Beyoncé and Chance affirm this value with unapologetically pro-black music that deifies and uplifts the black experience. The moment Beyoncé uttered “love God herself,” it quickly became the new “I met God, she’s black“—plastered across t-shirts and young black women’s Twitter bios. Chance’s line “Jesus’ black life ain’t matter/I know ’cause I talked to his daddy” was a radical statement on white Christianity’s recasting of the olive-toned Galilean Semite, drawing parallels between state-sanctioned violence then and now.

And if Jesus is metaphorically black, killed by Roman officers, then who else could mothers like Sybrina Fulton or Lesley McSpadden be other than black Madonnas mourning their crucified sons? Beyoncé deftly evokes this in “Lemonade” and furthers the symbolism in her Grammy performance, donning a golden halo with sunburst-like rays that hearkens to the Virgin Mary.

Both “Lemonade” and “Coloring Book” seem to represent two sides of the same black worship coin, one somber and reflective, the other exuberant and frenzied. Chance has always worn his faith on his sleeve—or on his head more accurately, the famous “3” cap he always dons representing both the Holy Trinity and the three mix tapes that defined his career. Beyoncé makes her spirituality a little more understated, leaving it to her audience to discern the meaning behind her art.

In our current milieu where “Christianity” has come to mean many and all things, it’s hopeful to see a loud, boisterous religious expression from these two black artists, one that praises and reinvigorates rather than condemning or decrying.

As Beyoncé said at the end of her show-stopping set, “If we’re going to heal, then let it be glorious.”