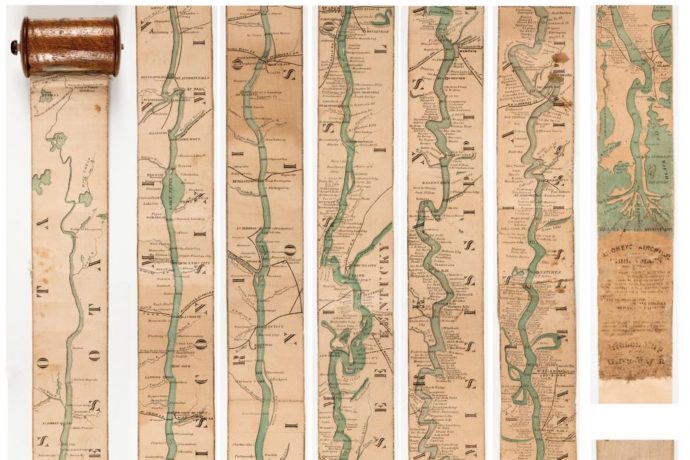

I have a friend who studies rivers. An art historian, she pays attention to representation, mainly how the Mississippi was imagined and presented to eastern, urban audiences back when it constituted the edge of the American frontier. She looks at paintings and popular forms like cycloramas, as well as maps—maps of all sorts, plotting cities and stopping points, charting currents and depths, organizing information about game and trade, weather and vegetation. But maps, she insists, do far more than orient. Maps also offer an experience, rich in detail but explicitly limited. Consider one of her favorite maps, a spooled ribbon that, as one unfurls it, replicates something of the flow of the river itself, giving the reader an experience of meandering down its length, a virtual journey.

All maps are subjective. They frame the selected information they offer to their viewers. By such framing, they tell stories, advance arguments. For those of us who study religion, necessarily concerned with how humans create and employ categories, maps serve as useful examples of that practice—maps on religion, doubly so.

“Remapping American Christianities,” a three-year editorial initiative here at Religion Dispatches, explores not only the diversity of religious community and practice but also the varied ways of approaching such an investigation, the technologies—old and new—available for organizing and imagining religion. Hence my interest in that ribbon map, in a model of mapping that embraces its subjectivity and explicitly offers not merely “data,” but also an experience.

Map is not territory, but a map is still something we traverse, or wander through. Who has not “visited” some new place via the street view simulation of Google Maps, or returned to once-familiar haunts, motivated by nostalgic longing? We are not there, but we are confronted with something more powerful and palpable than a mere idea of there—we are dislocated, even disoriented, by our experience of maps, made aware of where we are not.

Maps allow for a kind of immersive wandering, yet at the same time reminding us of our distance from that which we contemplate. This is an essential caution for considering any maps of American religion, from the robust—such as Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis’s Digital Atlas of American Religion—to the narrow—the Hindu American Foundation’s map of Hindus worldwide (with accompanying demographic information comparing “Hindus/Asian/Indian” favorably on various socioeconomic rankings to other racial and nationality categories).

Unlike other kinds of maps, maps of American religion must negotiate the difficulty of that term—what counts, what doesn’t, what options can be offered to those polled? The Pew Forum’s much-cited Religious Landscape Study offers multiple options within the umbrella category of “Christian,” then several “World Religions” under the umbrella category of “Non-Christian Faiths,” and options for “Unaffiliated (religious ‘nones’),” “Nothing in particular,” and “Don’t know.” For the religionist, these categories should be as exciting as the data linked to them (…who are these people who don’t know their religion, what is their background, their idea of what “religion” might mean or be?) but the categories themselves are also obviously, immediately flawed (…is it always a choice, between either Jewish or Agnostic, mainline Protestant or Buddhist?). The maps assembled here offer a geographic look at the demographics of those who identify under these religious categories (income, education, immigration status) as well as their engagement in Pew-selected “Beliefs and Practices” including “Interpretation of Scripture,” “Feelings of Sense of Wonder,” and “Belief in Hell.”

Other popular maps of American religion refrain from such detailed parting of “religious participation.” The Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies conducts the U.S. Religion Census every ten years, publishing data in various forms, including maps displaying “most popular religion, by county.” A Washington Post article on the project, while taking no issue with the value of “religious participation,” does not mention that this measure “was lowest in California’s Alpine County (4.3 percent), Hawaii’s Kalawao County (3.3 percent) and Nevada’s Esmeralda County (3.1 percent). The latter two have incredibly small populations, so are easily distorted by the religious inaction of a few.” Sociologist Bradley Wright, likewise taking the terms and data at face value, expresses surprise that “the areas with the most diversity also tend to have the lowest rates of adherence, which would seem counter-intuitive–at least from the perspective of Rational Choice theory. One might expect that more offerings, i.e., more types of religions, would promote greater involvement in religion.”

Involvement is also key to maps designed as explicitly in favor of or opposed to (specific types of) religion. The Marriage and Religion Research Institute’s “Mapping America” project correlates data on “adultery by religious attendance and marital status.” The MRRI “is dedicated to making available the social science data” to support their claim “(so far repeatedly upheld by the data) that the intact married family that worships weekly is the greatest generator of human and social positive outcomes and thus it is the core strength of the United States.”

Conservative political commentator Allen West offers three maps “of Islamic activity, mosques and refugees” on his website, describing the data contained with only one word: “disturbing.” The first map (as compiled by Salatomatic, an Islamic guide to mosques) compiled the number of mosques per state, while the second, using U.S. Department of State data, charts the number of refugees arriving in each state (from October 2014-July 2015), and the third offers “a compilation of Islamic terror activity by state” pairing the names of organizations with U.S. cities (for instance, Boca Raton, Florida, is flagged for “Al Qaeda”).

The source for this map’s data, the Investigative Project on Terrorism, runs a more comprehensive map on their own website, plotting “Court Cases” that “involve terrorist plots or financial and other forms of material support for terrorists” as well as “Mosques and Islamic centers listed at one time were home to radical clerics or to conspirators in a terrorism-related investigation, or had other connections to radical individuals or terrorist organizations” and “Radical Activities,” which are “multi-player criminal cases of terrorist plots or financing. In some cases, those activities have tentacles in more than one city.”

Contrast this sort of argumentative, interpretation-driven map with Grinnell College’s new Mapping Islamophobia project. This map takes the wise, engaging strategy of eschewing analysis in favor of data. Interactive maps offer detailed accounts of what the project calls “Islamophobic attitudes,” broken down into categories such as “Crimes Against People,” “Crimes Against Property,” and “Legislation,” but with more detailed descriptions for each individual event, from hate speeches to violent conspiracies (such as a 2016 plot by Kansas militia members to blow up a building in which Somali immigrants lived). Separate maps present this data by year, by type, and over time.

Even more in keeping with the sensual immersion of the ribbon map is the American Religious Sounds Project, a map, digital archive and online museum. A collaborative project of Ohio State and Michigan State Universities, the project emerges from an earlier pilot study, the Religious Soundmap Project of the Global Midwest. The current iteration seeks to map “varied sonic cultures” of diverse religious communities and their practices nationwide, drawing on students, scholars, and others from around the country. Melding interviews and oral histories with field recordings, integrating text and image (photographs accompany most of the sounds), the American Religious Sounds Project aims “to offer new insights into the complex dynamics of religious pluralism in the United States.”

The co-directors of this project, Amy DeRogatis of MSU and Isaac Weiner of OSU, suggest that we can understand religion and religious diversity differently “by listening for it,” but it is the field researchers who listen for while we, the audience, presented with online audio files, listen to, hearing an assortment of coughs and traffic noises, shufflings of bodies, backtalk and background sounds. We are given not studio recordings, after all, but aural field notes. In the kitchen at the St. Stevan-Dechani Serbian Orthodox Church Fish Fry, canned music from tinny speakers competes with the quick chopping of onions, the rattle of pans, the sizzle of hot grease. Is what we are listening to religion, or, to push the question, how does listening to this reorient us in terms of thinking about or studying religion?

This mode of mapping renders visible the subjective quality of maps in general. In the process of making religion audible, the American Religious Sounds Project makes ethnography audible too. These recordings call into question what counts—and has counted in the past—as data for religious studies while reminding us of the always partial, fleeting nature of witnessing “religion.” The ethnographer, neither an omniscient narrator nor Emersonian Invisible Eyeball, is, at best, a recorder in a room, for a limited amount of time and recording on only one wavelength. We have the sounds of cooking, but not the smell or the taste of that fried fish. While offering us what we would otherwise not hear, this project also highlights limitations that are always on us.

Such mapping exemplifies what anthropologist John L. Jackson, Jr. calls “thin description.” A corrective on what Jackson takes to be an overconfident, even arrogant faith in anthropological thick description, in the ability of the ethnographer to offer “complete and total knowledge,” “the self-satisfied belief that they’ve mastered some previously opaque other.” Thin description is, on the contrary, a style of ethnography that emphasizes the incompletion of knowing. Thin description gestures, but does not totalize. It tells stories, but does not purport to disclose all there is to know.

Rather than containing “religion” within the confines of a narrow, subjective category, the sort of “remapping” that should be celebrated makes explicit that it gestures toward something remaining always distant. The American Religious Sounds Project reveals that which could otherwise be ignored—the crying child, the restless congregants, the street traffic, the hustle of kitchen prep work—and while these sounds of human activity certainly do not explain or end the conversation on “religion,” they, once introduced, seem essential for contemplation of that term.

The best maps, offer only a sense of things, a limited measure, while simultaneously serving as an invitation to further exploration. The laughter at the North Clintonville, Ohio “Krampus Parade” gathering, as pagans and friends unite to banish the spirit of evil from the yuletide season with drums and bells and masquerade—or the more solemn drumming, accompanied by the steady pat of feet in a procession of Spanish-speaking Catholics in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe— these brief fragments of lived religion in the world serve to remind us how complicated this phenomenon of “religion” is.