On January 13, Liberty University, the world’s largest and most notorious fundamentalist college located in Lynchburg, VA, announced that Pastor Dane Emerick, who functioned as its in-house conversion therapist, had retired. This news comes to the delight and relief of many alumni who were subjected to his “counseling.” But some wonder whether Emerick’s retirement marks the end of Liberty’s conversion therapy program or whether another damaging counselor will pick up where he left off.

For decades, as Liberty’s “Dean of Men” and later as the Associate Director of Community Life, Emerick largely worked with two groups of Liberty students: men who “struggled” with pornography “addictions,” and men who “struggled” with “same-sex attraction” (that is, queer men who didn’t want—or were told they didn’t want—to be queer). According to the fundamentalist imagination, both groups of individuals are in desperate need of spiritual and sexual repair. Yet, despite how most within the fundamentalist fold would prefer to ignore the so-called evils of porn and homosexuality, Emerick took it upon himself to war against both—as a paid employee of Liberty, an institution that receives federal funding, no less.

Emerick met with hundreds, if not thousands, of male students individually or in group-settings throughout his tenure at Liberty. I was one of them. Over the past year, I’ve written a few articles about my experience in conversion therapy with Emerick in one-on-one meetings and about the time I attended one of his group meetings that was dubbed “Band of Brothers.” In response to my articles, I’ve received an overwhelming number of messages from other Liberty alumni who suffered, but survived, Emerick’s specious counseling. I reached back out to these men, some of whom agreed to share their experiences here. You will of course read reports of pain and struggle, but you may be surprised by the feelings expressed about Emerick himself.

Joshua Grubbs, a 2010 graduate, explained his involvement with and thoughts on Emerick this way: “I participated in his porn groups, and I honestly think that he is a perfect example of how great intentions and a kind heart can be destructive as hell when your beliefs are wrong. I think Dane genuinely thought he was helping people, but his theology was inherently harmful.” As is suggested by Grubbs, who’s now an Assistant Professor of Psychology and an expert on porn consumption, Emerick was, in truth, not malicious or malevolent in his intentions to “fix” us students. But as intentions matter not, and as the damage of Emerick’s work was indeed done, it remains clear that the school’s long-time conversion therapist has much to account for.

David Coomer, who also graduated in 2010, described his relief that Emerick’s time at Liberty has come to an end: “I am happy he cannot hurt students anymore with his lies and deceit.” Coomer, now living in Richmond, VA, underwent several years of conversion therapy with Emerick, but what stands out in his memory is the emotional manipulation: “He would guilt trip me into confessing my ‘sin.’ And he always addressed me as ‘kid,’ like he was being sweet or something. And he often said, ‘I love you, kid.’”

Tyler Milton, a 2016 graduate who also underwent conversion therapy at Liberty, remembered Emerick this way: “He was so warm, so friendly, and was a very paternal figure. And I really think he took advantage of that nurturing quality.”

Coomer and Milton’s memories of Emerick are strikingly similar to my own. In my one-on-one meetings with Emerick, he always asked me if I had “slipped up” that week—that is, if I had acted on my sexual desires. “Slip ups” could include anything from looking lustfully at other men to looking at pornography to flirting to, well, anything Emerick said was sinful. During these uncomfortable question-and-answer sessions, Emerick would assume the “love the sinner, hate the sin” posture. However, I, like Coomer, would consistently feel guilty for not following the straight-and-narrow (pun of course intended). And, as was also the case with Coomer, Emerick’s guilt trips were inevitably tempered with him telling me that he loved me.

The problem, however, was that Emerick’s “love” for us queer students was always emphatically misleading. His “love” bifurcated us queers into two compartmentalized parts: that which was “sinful” (the gay part of us) and that which was non-sinful (the “rest” of us). The former was condemnable, the latter “loveable.” Such “love” never embraced us for who we were; it embraced us, rather, for who Emerick wanted us to be.

Yet, the damage of conversion therapy didn’t end with our time at Liberty. The enduring psychological consequences of conversion therapy—like, for example, shame, anxiety, and self-hatred—are legion, which is why the debunked practice has been denounced as dangerous by all reputable scientific and professional organizations, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Psychiatric—and the list goes on (and on).

But like many fundamentalist institutions, Liberty sees no issue with this bogus practice. Instead, the university finds much to celebrate in regard to Emerick’s attempts to fight against homosexuality. In fact, in Liberty’s official announcement of Emerick’s retirement, the school describes Emerick as a “campus counselor and mentor,” who “leaves [a] legacy of love at Liberty.”

Emerick’s “love”—his largely hollow sentimentality masquerading as care for queer students as queer students—was and is insidiously lacking. When we queers (inevitably) failed to meet the standard of sexual “purity” that Emerick “lovingly” established for us, we came to experience profound guilt, as Coomer suggests above. The guilt we felt was of course a function of the fundamentalist belief that homosexual activity is immoral. But Emerick’s “love” amplified such guilt, compounding our negative responses to our sexualities, especially given his role as a father-like “mentor.”

In Liberty’s announcement of Emerick’s retirement, Mark Hyde, Liberty’s Associate Dean of Students, is quoted as saying that Emerick is not only “one of those unsung heroes for Liberty,” but that he “deserves congratulations for all of the work that he has done. He is certainly going to receive treasures in heaven.”

The “work” that Hyde references is in large part Emerick’s meetings with queer students. But in typical fundamentalist fashion, neither Hyde nor Liberty makes any mention of Emerick’s decades-long work as a conversion therapist—nor, for that matter, is there any mention of conversion therapy anywhere on Liberty’s website. As is common with most practitioners of conversion therapy today, despite their belief that sexual orientations and/or gender expressions can be changed, they don’t publicly advertise their ineffective and deeply damaging “therapy.”

Another survivor of Emerick’s conversion therapy, a 2017 graduate who asked to remain anonymous, explained why it is that Liberty is not explicit about offering conversion therapy. “They don’t market it as conversion therapy,” he said. “They market it as support for same-sex attraction, so they’re not catching heat.”

Despite Liberty’s lack of advertising, the school, under the supervision of Emerick, has been clandestinely operating its program for decades. But since the school has refused to make its shameful conversion therapy operation publicly known—and contrary to Liberty’s laudatory portrayal of Emerick in their retirement announcement—several of us have made it our duty to bear witness to how Emerick tried, but unsurprisingly failed, to make us straight.

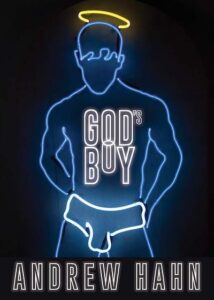

Andrew Hahn’s Poetry Collection, God’s Boy (2019)

Andrew Hahn, a 2013 graduate, has been a front-runner in writing about his experience as a queer man at Liberty. The author of God’s Boy—a deeply poignant yet heart-breaking collection of poetry about being queer at Liberty and in Lynchburg—partially details his experience with Emerick. When Hahn and I recently spoke, he said: “I don’t know if he told you this, but he [Emerick] told me I was going to kill myself; over and over again he told me that.” Emerick’s declaration that Hahn was going to kill himself is not uncommon in conversion therapy; many conversion therapists are convinced that queers are fundamentally unhappy because of their attraction to the same gender and are therefore prone to taking their lives.

Of course, what conversion therapists don’t seem to understand is that if it weren’t for their and others’ acute attacks against us queers, we would be significantly happier and would be much less prone to suicidal ideation. It is conversion therapists who contribute to this problem, not queer individuals themselves.

Hahn, further reflecting on Emerick’s retirement, explained: “I am so happy he’s gone. But while I’m relieved Emerick is gone, I can’t help thinking about the generations of queer people he’s irrevocably damaged during his ‘ministry.’”

Hahn’s concern for the many queer alumni and students at Liberty is eminently justified, especially given Emerick’s parting words, which are, simply put, chilling: “When someone asks me how many children I have, I tell them three daughters and thousands of sons.” This disturbing sentiment hints at the overwhelming number of students who were habitually subjugated to Emerick’s chaotic work.

The question, however, remains: While neither he nor Liberty referred to him as a therapist of any kind, how was it legal for Emerick, someone who’s not a licensed therapist, to get away with offering such services? The first part of the answer is that for the majority of the time Emerick was offering conversion therapy, there were no anti-conversion therapy laws in place. The second part is that anti-conversion therapy laws, as they currently stand, have a number of limitations. Mathew Shurka, the Co-Founder of Born Perfect, an organization that works to protect LGBTQ+ youth from conversion therapy, explains it this way:

“The [conversion therapy ban] that passed in Virginia makes it illegal for any licenced professional attempting to do conversion therapy on a minor. Any university such as Liberty University that has a licensed professional doing conversion therapy on someone under the age of 18 would be breaking the law.”

However, since almost all students who matriculate to Liberty are above the age of 18, such a protection would not have applied. In truth, those over the age of 18 are protected under consumer fraud laws. But since Emerick always framed his services as “pastoral counseling”—a broad umbrella term that does not require a professional therapy license—and since there was no direct monetary exchange between Emerick and his “thousands of sons,” such laws would also not apply.

In either case, Hahn and I, along with several other queer alumni, have made it our goal to make clear that despite his good intentions, Emerick was responsible for wreaking havoc on queer students’ young, vulnerable, and impressionable minds—the wounds from which are still healing for many of us.

But I, like Hahn, am concerned that conversion therapy at Liberty will continue. “I’m hoping conversion therapy will stop, but there’s always going to be some Christian man who hates queer people,” Hahn explained. “I think it will continue because of the hate toward us in Baptist communities.” Of course, only time will tell if Liberty will continue its dirty work of trying to turn queer students straight, but one thing remains clear: Liberty continues to be a proudly homophobic university that revels in its disdain for the LGBTQ+ community. As Tessa Russell, a 2020 graduate, indicates in her recent article about being a lesbian at Liberty, homophobia is alive and well on campus—something that should be of significant concern for Liberty’s accrediting body, the Southern Association of Schools and Colleges.

Although I don’t expect Liberty to be on the right side of history and denounce its homophobia any time soon, I do hope that we queer Liberty alumni will continue to draw attention to the bigotry that runs rampant at the world’s largest fundamentalist university. Liberty and Emerick had their opportunity to try to change our sexual orientations, but it ought to be known that today many of us are thoroughly, delightedly, and proudly queer. Indeed, despite how Liberty sought and continues to seek the erasure of queer life on (and off) campus, it is we queers who will have the proverbial last word.