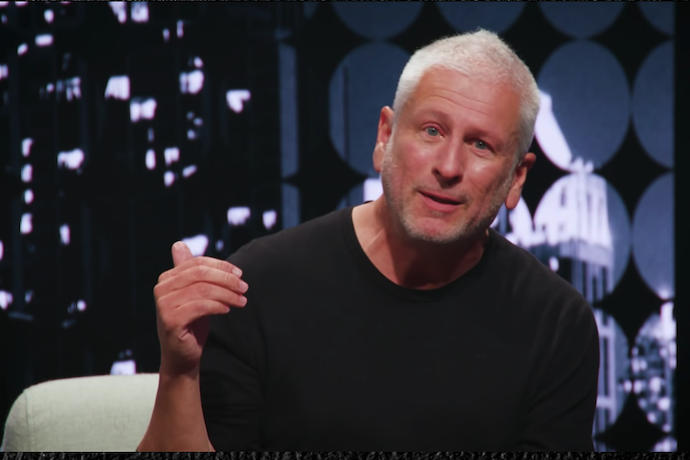

On June 14th, as the city of Atlanta reeled from the murder of Rayshard Brooks at the hands of white police officers two days prior, white evangelical Christian pastor Louie Giglio hosted a panel on race at his Passion City Church. While sharing the stage with Black Christian rapper Lecrae and Chick-fil-A CEO Dan Cathy, Giglio said the following:

“We understand the curse that was slavery, white people do, and we say that was bad, but we miss the blessing of slavery, that it actually built up the framework for the world that white people live in and lived in.”

Giglio went on to suggest replacing the phrase “white privilege” with “white blessing” to avoid antagonizing white audiences in discussions of race.

The social media reaction was swift and incisive. As religious studies scholar Anthea Butler put it, “Giglio said what was true to him and what’s true to a lot of evangelicals, but it doesn’t make it right.”

Giglio posted a tearful apology two days later, noting, “White privilege is real. And in trying to get that sentiment across on Sunday, I used the phrase ‘white blessing’, for which I’m deeply sorry. Horrible choice of words—it does not reflect my heart at all.”

The word choice is indeed jarring—so much so, in fact, that it risks hijacking our attention from the context that produced it. Yes, “blessing” is an appalling substitute for “privilege,” but the issues with Giglio’s statement run deeper than semantics. Why did Giglio think the language of “white privilege” needed tinkering to begin with? And what role, if any, can Giglio’s apology play in making amends?

To answer these questions, we need to shift our focus away from what Giglio said to what his comments and subsequent apology did. Giglio’s instinct to avoid triggering white audiences with language of privilege enforced a pronounced tendency in evangelical circles to conform race discourse to white sensibilities (it’s worth noting that the leadership team of Passion City church is overwhelmingly white despite being headquartered in a predominantly black city). And while the thoughtful wording of the apology contrasted nicely with his earlier verbal carelessness, its emotionally effusive delivery focused attention on the affect behind the words. This replicated the centering of white feelings that routinely undermines substantive discourse on race issues. Both the initial comment and the apology underscore how easily the American evangelical emphasis on emotion becomes a means of centering white affect in ways that perpetuate white supremacy—and how even sincere attempts to address white supremacy become means of replicating it.

This is not to suggest that emotion in evangelicalism is problematic per se. Spiritually speaking, the whole range of human emotion has potentially productive uses. This is true even of the uncomfortable emotion that Giglio sought to sidestep: offense.

For evangelicals, feelings offer crucial insight into one’s spiritual state. Spiritually healthy people manifest emotions that fit the matter at hand: anger at injustice, remorse for wrongs done to others, gratitude for second chances, etc. Emotions that are out of sync with the situation—complacency at injustice or relishing cruelty, for example—can be a sign of spiritual sickness. Within this framework, giving or taking offense plays a key diagnostic role. True friends point out when we’re wrong even at the risk of offending us. Attentive spiritual leaders do the same for their congregations.

Following this logic, Giglio’s initial error was in viewing the offense taken at the term “privilege” as something to be avoided. Whatever Giglio’s intent, this strategy sent the message that forthright conversations on race aren’t worth the risk of offending white people, thereby undermining the very racial justice work he claims to support.

Which brings us to his apology. By all appearances, it was heartfelt. But as theologian Kyle J. Howard and others have noted, it perpetuates the pattern of centering the feelings of white people in a way that further undermines the work of racial reconciliation.

Emotionally demonstrative performances of remorse follow a well-worn penitential trope in evangelical culture. Emotionless, muted, or rote confessions suggest the need for further penance. Sorrowful confessions suggest full inward transformation, and thus, are grounds for absolving the individual of wrongdoing (as Sinclair Lewis famously depicts in the closing scene of his classic satirical novel Elmer Gantry).

A quick glance through the comment thread confirms that, to his evangelical audience, Giglio’s tearful confession rates as strong and convincing. But it sends the message that undoing white supremacy is a matter of white inward transformation: that the difference between racism and antiracism is simply a matter of affect. While the focus has shifted from offense to confession, white emotions remain front and center.

Undoing white supremacy requires structural change that decenters white concerns. To join this process, white leaders like Giglio need to acknowledge that they’re on the periphery of racial justice work that’s been unfolding in communities of color for generations. They must model for other white people how to learn from and support this work without placing themselves at the center of it.

Giglio’s twitter bio provides a helpful image for this decentered supporting role: “Happy to be a door holder.” If Giglio’s confession is the beginning of him holding the door for race discourse rather than taking center stage, then perhaps it will mark the start of something meaningful. In the meantime, we have to be honest about how his words and actions center white emotion in ways that prop up white supremacy.