According to police, a 17-year-old student fired 10 shots into the cafeteria of his Louisville, KY, high school last week, killing 16-year-old Josselin Escalante and injuring an unnamed student before turning the gun on himself.

A manifesto circulating online paints the alleged Antioch High School shooter as a young Black man who absorbed white supremacist social media and dedicated himself to anti-Black mass murder. Self-identifying as “N-cell” (presumably a play on “incel,” meaning “Involuntary N—”; censorship mine), he echoes anti-Black tropes; cites racist mass shooters and Candace Owens among his inspirations; and argues that in the interest of creating a “better, neater, cleaner world by eliminating all undesirables we must aid the Aryans regardless of our race.” According to ProPublica, extremism researchers note that he participated in online networks that glorify white supremacy and mass shootings.

But the alleged shooter’s Kik handle, “HonoraryYakubian,” which references a mythological figure named Yakub, suggests he might also have been influenced by Nation of Islam lore. If that’s the case, how did an anti-Black mass shooter come to identify himself using the teachings of Elijah Muhammad? If it’s not, then where did the handle come from?

Yakub, white supremacy, and mass shootings

According to the Nation of Islam’s foundational texts, an ancient, literally “big-headed” eugenicist named Yakub created white people on the island of Patmos 6,000 years ago. Nation leader Elijah Muhammad taught that Yakub’s creations were devils, bent on the humiliation and destruction of Black people.

Nuwaubian depiction of Yakub. Image: Fair Use

But the shooter’s writings do not actually suggest substantive knowledge of the Nation of Islam or Islam more broadly. If anything, his manifesto—like so much global far-right rhetoric—reveals disdain and disgust for Muslims. The writer calls Muslims “Mudslimes,” and describes an image and video clip of the Christchurch mosque shooting as the “best 16:55 minutes of pure gameplay.” He echoes anti-Muslim tropes about the Prophet Muhammad’s marriage to A’isha, saying “muslims worship a dead pedophile,” and credits Christianity for defending Europe from “Islamification in the past” while dismissing modern Christians as “too passive.”

The Antioch High School shooter’s self-identification as an “honorary Yakubian” doesn’t align him with the Nation of Islam, but rather with white supremacists’ curious fascination with and adoption of NOI doctrines and tropes—a fascination with a well-established history. American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell, for example, attended Nation of Islam events in the early 1960s. In the 1970s, Wyatt Kaldenberg’s encounters with Nation teachings led the racial separatist and neopagan author to seek an Aryanist religion, inspiring him to explore Asatru and Odinism and later embark on his own project of recovering pre-Christian European traditions. The gunman in the 2022 Edmund Burke School shooting hung a poster of Yakub in his apartment.

Today, Yakub has found a new life in the weaponized irony of right-wing meme culture. While the story comes from early NOI writings, Yakub memes originated in the Nuwaubian movement, which emerged in 1960s Brooklyn and whose rich corpus of visual art includes numerous depictions of Yakub. Since the mid-2010s, 4chan users have circulated Yakub memes, many of which depict him with an exaggerated, bulbous cranium. Posting photos of people with large heads became known as “Yakub-maxxing.” Zoomers on social media are increasingly making references to Yakub, to the confusion of older users, with some even suggesting that my writings might have instigated this trend.

Resignifying Yakub

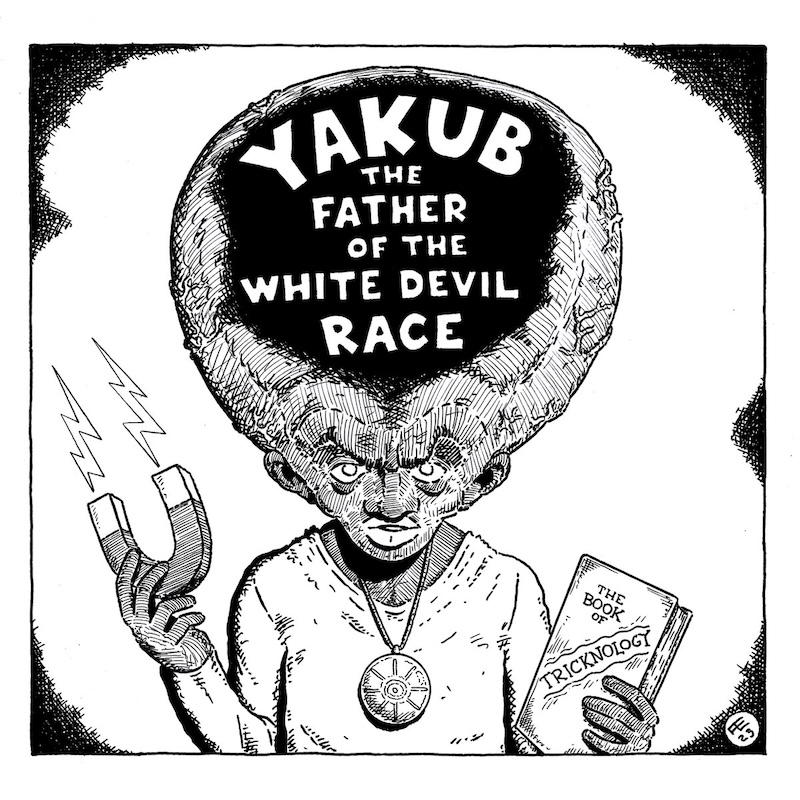

In fact, much of the current rise of Yakub lore in Online Right circles appears related to right-wing cartoonist Frank Edward’s graphic novel, Yakub: The Father of the White Devil Race (2023), which retells the Yakub story mostly in tune with the Nation’s canonical outline while embellishing certain details. The illustration of Yakub is based on the Nuwaubian-derived meme image (above) with added racist caricature. Edward’s retelling reads like a blackpilled fantasy in which young Yakub, victim of an unfair social order, sets out to destroy the system.

As in Nation canon, Edward’s Yakub displays extraordinary intellectual gifts as a young child; but in Edward’s telling Yakub experiences social rejection and isolation at the royal court due to his “commoner blood,” which leads to him harboring desires for violent revenge. Lonely autodidact Yakub spends his time alone, deep in research, before starting a new religion he calls “Tricknology.” As the once-bullied Yakub takes his message public and rapidly gains followers, Edward writes, “The women that once mocked him now desired him, and the men that once slighted him now began to respect him.”

Yakub’s growing popularity as a divisive edgelord puts him at odds with the “official state religion,” leading to violent clashes in the streets and ultimately to the state deporting him and his followers. Sailing the seas in exile, formerly incel beta Yakub assumes his new chad role and monopolizes sexual access to his thousands of women followers, personally impregnating all of them. Edward’s Yakub emerges as an incel hero, disrupting the system that rejected and scorned him.

The appeal of Yakub to disaffected young people like the Antioch High School shooter becomes clearer in the light of Edward’s version, in which Yakub is the victim of an unfair social order who seeks revenge and works to obliterate the system that rejected him. This Yakub is powerful, popular, and potent—all of which are grievances and desires expressed in spaces that encourage young people toward public violence.

While Nation of Islam scholars might be astonished to see white supremacist appropriations of Yakub lore, the meanings of Yakub—like any sacred history—have historically been malleable and diverse. Elijah Muhammad’s son, Wallace D. Muhammad (later Warith Deen Mohammed), reinterpreted his father’s teachings about Yakub’s “white devils” as allegorical. In 1975, he taught that “devil” signified a particular state of mind, not an inescapable fact of biology.

Former Nation member Clarence 13X Smith, who in 1964 changed his name to Allah and led the Five Percenter movement, taught his students (including white disciples) that when God and the Devil walked hand-in-hand, there was no longer a Devil. In contrast to ironic appropriations of Yakub by the Online Right, numerous white students of Nation tradition (known as “Muslim Sons” and “Muslim Daughters”) have read the canonical lessons through a lens of critical antiracism, seeking to undo Yakub’s world both in their own selves and the structures that manufactured them. The Online Right’s strange appropriation of Yakub as an incel hero, like the Five Percenter’s antiracist implementation of a foundational Nation theodicy, could produce a wave of meanings that neither the Nation’s founders nor the Online Right ever expected or intended.