What inspired you to write The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences?

On a clear afternoon in March 2011, I was at a Tantric Buddhist tattoo parlor in Kyoto when the radio broadcast we were listening to was interrupted with news of the devastation that was the Tōhoku earthquake. The extent of the damage was still unclear, but as reports continued to come in, the tattooing process was stopped so that everyone in the parlor could gather together before the single TV.

During our anxious wait, we fell into small talk, and I mentioned the project I was in Japan to research at that time (tentatively titled “Ghosts and Resurrections: Shifting Boundaries between the Living and the Dead in Modern Japan”). In return, people shared anecdotes with me about various protective talismans and ghostly premonitions. After a number of the patrons had shared such anecdotes, one Japanese man asked me, curiously, if these sorts of things didn’t go on in America. Before I could answer (and describe America’s own enchantment), a European patron jumped in, assuring everyone that Japan was much more spiritual and magical than the West. He looked to me to confirm the sentiment, which I did my best to refute. But that reflexive response reinforced in me a suspicion that had been bothering me for some time already—which was that by continuing to use Japanese history to challenge the thesis that equated modernity and disenchantment, I risked reinforcing harmful (and incorrect) clichés about a mystical Orient, when my aim was in fact to undo the pervasive myth of modernity.

It was out of this moment of disruption, then, that I switched tracks from the project I had been working on and onto the beginnings of what would eventually become this book.

A great many theorists have argued that the defining feature of modernity is that people no longer believe in spirits, myths, or magic. This is often supposed to be true of America and Western Europe if nowhere else.

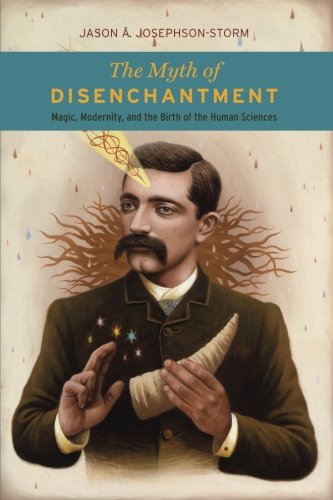

The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences

Jason Josephson-Storm

University of Chicago Press

May 2017

However, I knew full well that many Americans and Europeans also believed in protective icons and spiritual premonitions. In fact, my grandmother was a famous professor of anthropology who after her retirement went public with her belief in spirits and ecstatic trances; throughout my childhood I remember scholars, scientists, and artists travelling from Europe, Mexico, and the United States to participate in “shamanic” trance workshops under her leadership. My grandmother inspired me to become a scholar, but I was always skeptical of spirits, and moreover I was doubly skeptical of the notion that the modern Western world had lost its magic.

I found myself shifting gears and looking at America and Europe through the eyes of an outsider—with the same sort of gaze often leveled at non-Europeans. When I did so I discovered that the sociological data suggested that the majority of Americans believe in ghosts or demons. Indeed, a surprising 73% of Americans have at least one paranormal belief, and while the data is less robust it looks like there are similar belief patterns in Western Europe. At the very least, it seems hard to argue that the “modern West” is straightforwardly disenchanted. So I asked myself how did we get the notion that “modernity” (and what it is said to entail) equated with an end of belief in magic and spirits?

The issue becomes even more troubling when you realize that the canonical European theorists (anthropologists, sociologists, philosophers and so on) who came up with the various accounts of modernity as disenchantment lived in the nineteenth century in the midst of spiritualist and occult revivals. Magic and séances were on the surface of European culture at the very moment that Europeans came to argue that magic had vanished. So I began to ask: how did this narrative of modernity become dominant? Put differently, how did a magical, spiritualist, mesmerized Europe ever convince itself that it was disenchanted? And that was what I set out to answer in The Myth of Disenchantment.

“Higher education levels do not directly result in disenchantment. Indeed, one might hazard the guess that education allows one to maintain more cognitive dissonance rather than less.”

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

The story of disenchantment we have told ourselves is a myth. We tend to the think of the “West” as disenchanted. But the majority of people in Europe and America believe in magic or spirits today, and it appears that they did so at the high point of so-called “modernity.” And contrary to what you might think, higher education levels do not directly result in disenchantment. Indeed, one might hazard the guess that education allows one to maintain more cognitive dissonance rather than less. Secularization and disenchantment are also not correlated. Moreover, it is easy to show that, almost no matter how you define the terms, there are few figures in the history of the academic disciplines that cannot be shown to have had some relation or engagement with activities or ideas that their own epoch saw as being in some way magical.

Modernity is a myth. The term “modernity” is itself vague. There can, occasionally, be value in vagueness, but “modernity” here rests on an extraordinarily elastic temporality that can be extended heterogeneously and in value-laden ways to different regions and periods more or less at the whim of the theorist . It can also pick out or highlight different processes such as urbanization, industrialization, globalization or capitalism—but these are indistinct and given different weight at different times. Moreover, when described in terms of the de-animation of the world, the end of superstition, the decay of myth, or even the dominance of instrumental reason, “modernity” is meant to signal a societal rupture that never actually occurred.

Basically, this book aims to retell the grand narrative of European history. It is a challenge to most conventional notions of what “modernity” means. A whole host of theorists—from critical theorists, to cultural critics, to contemporary policymakers—often share a notion that there is something exceptional about modernity and the thinking it has produced. But I argue that this notion too is suspect.

This implies a need to re-conceptualize the history of the academic disciplines. For scholars in a range of areas (from religious studies to anthropology to psychology to sociology and modern philosophy), I show that founders and canonical thinkers in these areas worked out their various insights inside an occult context, in a social world overflowing with spirits and magic, and how the weirdness of that cultural milieu generated so much normativity.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Is there anything you had to leave out?

There is a lot I had to leave out. I tend to overwrite, and the first draft was massive and I had to cut a lot. So I ended up eliminating rough chapters on French social theory, American philosophy, Japanese accounts of Western Esotericism, and German Monist Leagues.

One of the hardest bits to cut was a short section on the American philosopher William James. Probably everybody has heard of his importance in the history of pragmatism and psychology, but it is a little less well-known that he was extensively involved in paranormal research—investigating spirit mediums, haunted houses and the like, and that he came to believe in the reality of some of the stuff he investigated. One of James’s most quoted statements is: “If you wish to upset the law that all crows are black, you must not seek to show that no crows are; it is enough if you prove one single crow to be white.” But the very next lines are, “My own white crow is Mrs [Leonora] Piper. In the trances of this medium, I cannot resist the conviction that knowledge appears which she has never gained by the ordinary waking use of her eyes and ears and wits.”

James’s psychical research while not common knowledge is little bit better known that many of the thinkers I discuss in the book. So I had to leave it out.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

“It was specifically in relation to this burgeoning culture of spirits and magic that European intellectuals gave birth to the myth of a myth-less society.”

First, the main thesis I critique—that modernity meant disenchantment—is pretty widely taken as a given in a range of disciplines. It just seems intuitively true to a lot of people. So in that sense I’m focusing on a significant misconception at the core of the project.

Second, when I tell people about the title of my project they tend to assume that I’m arguing that nothing changed. But actually, I argue that there have been significant social/epistemic status shifts. Basically, “the myth of disenchantment” is a “real myth.” Many people believe in it and accordingly it does indeed have real effects. And in the book I trace how it came to function as a regulative ideal, the myth itself producing both enchantment and disenchantment. Indeed, I show that it was specifically in relation to this burgeoning culture of spirits and magic that European intellectuals gave birth to the myth of a myth-less society—a claim that was simultaneously celebrated as progress and lamented—often while being described in terms of rationalization, divine death, and fading magic.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

I’m trained in Religious Studies (with a background in philology, continental philosophy, and history), but I tried not to presume that the reader had much background beyond a basic familiarity with the names of some of the thinkers I engage with.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

In this work in particular, I’m trying to defamiliarize or render strange the European intellectual tradition that gave birth to the academic disciplines. I’ve also uncovered that a number of famously “modern” intellectuals held unusual religious/spiritual beliefs that that their later followers and even critics tend to be unaware of—and might be pissed to discover/have exposed. Still, I’d rather be controversial than uphold a misguided status quo!

What alternative title would you give the book?

I had always meant for the title to be “The Myth of Disenchantment,” but when I finally submitted the manuscript to the press I was requested to provide a few alternate options for consideration, which included:

1) The Myth of Modernity

2) Magic Never Vanished

3) The Myths of Reason: Inventing Disenchantment and Modernity

I guess I really liked all of these for different reasons. But my editor decided to go with the working title, which in my opinion was the right choice.

How do you feel about the cover?

It rocks! The cover we ended up with is by an artist (Alex Gross) whose work I’ve been collecting for a while now, and I think it does a great job artistically hinting at some of the book’s main themes. In my eyes, it illustrates a figure who is simultaneously scientific and enchanting, which is as good a personification of “the myth of modernity” as I could have hoped for.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

I wish I could have written Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment. It’s a classic, and although I don’t agree with everything in it, it’s the main text I’m responding to in the Myth of Disenchantment.

More recently, I really loved Rita Felski’s The Limits of Critique. It really anticipates some things I’ve been working toward in my next book. To have her say them first is nice because they are out there, but in other ways she really beat me to the punch. Plus, her prose is wonderful and poetic.

What’s your next book?

I’m pretty far along in the first draft of a new manuscript called “Absolute Disruption: The Future of Theory after Postmodernism.” It was mainly born in the same moment as The Myth of Disenchantment. Originally, I thought I was working on one big book on “The Past and Future of the Human Sciences” but I realized that the work I needed to put into articulating the history of the humanities/social sciences looked very different from how I wanted to articulate where I think we should go next. So the two works are quite different from one another stylistically, but a pair in terms of project.

“Absolute Disruption” is an attempt to challenge some dominant modes of scholarship today—those that are often associated with postmodernism. Basically, the decay of master narratives has led to a near-universal distrust of universals, while the proliferation of branching particularities seems to promise nothing but further fragmentation. My task was to find a way forward that rejects both modernist essentialism and postmodernist skepticism. So the response I am putting forward is neither deconstructionist nor restorationist—instead I articulate the need to locate the negation of the negation. To skirt a cliché, I argue that we need a Copernican revolution. We need to revolve the whole enterprise on its axis. The center must shift if the human sciences are going to hold. In sum, I aim to move beyond deconstruction by radicalizing it or turning it inside out. So, the new book will articulate new methods for the social sciences by simultaneously radicalizing and moving past the postmodern turn.