Riding high from his tenure as the moderate governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney was anxious to accomplish what his father could not: jump from state’s top job to the nation’s. But to move from the governor’s mansion into the White House, he had to convince evangelicals that they could cast their allegiance to a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

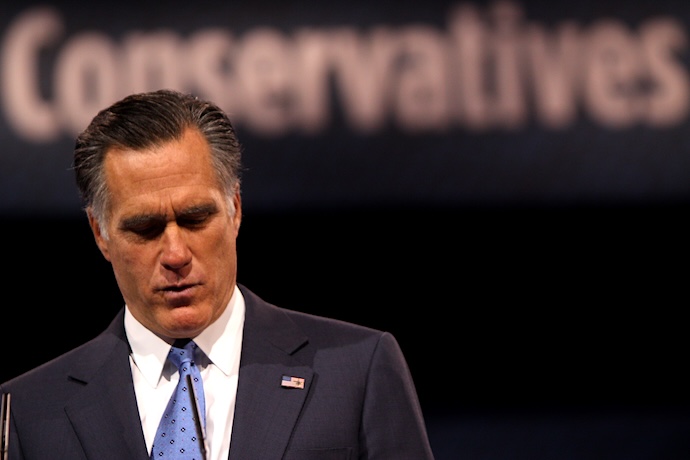

Romney: A Reckoning

McKay Coppins

Scribner Book Company

Oct 24, 2023

And so Romney met with a group of prominent evangelical leaders in his home outside of Boston in late 2006. Yet what he hoped would be a disciplined exchange concerning interdenominational cooperation instead turned into an “inquisition.” Jerry Falwell pressed him on Latter-day Saint beliefs concerning God. Richard Land wondered why Mormons had rejected the Nicene Creed. And Franklin Graham critiqued him for appointing two judges who were gay.

In the end, Romney’s team felt the meeting, which dragged on with substantial back-and-forth, went as well as could be expected. They felt that the two sides had found at least some common ground. But Romney felt bewildered by the zealous ideologues. And when evangelicals failed to support him in his 2008 campaign, his skepticism proved valid.

The previously unreported meeting is just one of many fascinating anecdotes in McKay Coppins’s new biography, Romney: A Reckoning. Political pundits have already highlighted the salacious details in this riveting tale of how Romney evolved from the GOP’s “standard-bearer” to “party pariah,” and what that decline says about the fate of American conservatism.

But given Romney’s significant place in the broader story of American religious history—he was the nation’s first Mormon to be nominated for president by one of the two major parties—it’s also an important text for the nation’s story of religion.

Romney isn’t a book about Mitt’s Mormonism. And yet, Coppins admits that Romney chose him as his biographer because Coppins, himself a Latter-day Saint, would “get the Mormon thing.”

There’s something deeply Mormon about Romney’s tale. But it has even more to tell us about Mormonism and its place in modern America.

The ‘Mormon problem’

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ nearly 200-year history, few individuals have received as much media attention as Mitt Romney, who became the public face of the church. His 2012 campaign (when he finally received enough Republican support to become the party’s nominee) played a central role in what was dubbed the “Mormon Moment,” a period of intense public scrutiny that included Broadway musicals, publicity campaigns, and incessant media coverage.

What’s remarkable, however, is how little Mitt’s campaigns resembled his father’s. When George Romney, a popular governor in Michigan, ran for the GOP’s 1968 nomination, his religion played a minimal role. If anything, Mormonism was considered an asset for the moderate politician, a symbol of his hearty work ethic and pioneer ancestry.

Mitt took advantage of his family’s relaxed environment. His mom had even urged him to join his high school’s smoking club as, in his words, “a kind of Mormon rumspringa.” (He ended up joining, but never attending.) Juvenile pranks resulted in him being arrested three times, episodes he was able to escape without lasting damage due to his father’s position.

As he grew, of course, Romney became better at toeing the line in both religion and life. He served a mission for his church in France, where his victories came in the form of renewed faith rather than numerous converts. And he married his high school sweetheart, Ann Davies, whom he did succeed in converting to the faith. (When, as a senior in high school, he leaned in to kiss her one night, she asked, “what do Mormons believe?” They ended up staying up to talk religion.) Eventually Romney became a successful businessman and distinguished church leader. It was only then that he hoped to follow his father’s example into politics.

But much had changed in the four decades that followed George’s campaign. (He had lost the nomination in 1968 not due to his faith, but because he said he’d been “brainwashed” into supporting the war in Vietnam as well as the party’s turn to Nixonesque extremism.) The rise of the Christian Right threatened the cultural gains Mormons had won through assimilation, because evangelicals were wont to highlight their alleged “heresies.” But it also offered an opportunity for the Latter-day Saints to join the interdenominational coalition, so long as they could deliver on designated social battles.

Religion had also become a crucial wedge issue in partisan politics. George Romney, who had never faced serious scrutiny over his Mormonism, was so incensed when Ted Kennedy attacked Mitt’s faith during their 1992 senate battle that he couldn’t hold back an outburst during a press conference.

But Mormonism truly took center stage during Mitt’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns. When evangelical candidate Mike Huckabee invoked the “Mormon problem” in December 2007, Romney refused to budge from his “core values” and instead delivered a “Faith in America” speech that was meant to do for him what John F. Kennedy’s speech on Catholicism had done in 1960. It was to no avail. But Romney had better luck four years later when he found a way to speak of his religion in ways that emphasized cultural commonalities with evangelicals, even if it meant muting theological differences.

Coppins’s biography details these important shifts in ways that will prove crucial to those interested in religion and politics in America. But it also points to other, more personal, cultural shifts that arise from Romney’s tale.

Valiant sacrifice vs. predetermined triumph

What makes Coppins’s book so riveting is an insider access rarely matched in political biographies. Romney gave him thousands of pages of journals, emails, and text messages, as well as hours upon hours of interviews. The degree of vulnerability is astounding. “I had never encountered a politician so openly reckoning with what his pursuit of power had cost,” Coppins noted, “much less one doing so while still in office.” Romney’s struggle to understand his own complicity in the Republican power struggle that resulted in the rise of Trump is reminiscent of classic Mormon tropes concerning guilt and repentance.

Max Mueller has already noted that an obsession with journal-keeping is a quintessential Mormon project. So is self-reflection. Latter-day Saints are taught from an early age that written records are part of a heavenly archive destined to tell the story of God’s chosen people. Romney’s copious notes on his senatorial colleagues and personal reflections spring from an anxiety to detail a sacred drama that plays out in everyday life.

Yet there are limits to the centrality of Romney’s religion to his politics. One of the book’s throughlines is Romney’s discomfort with people claiming a special providence, especially those who state that God had called them to a particular race. At different points in the narrative he critiqued both Mike Huckabee and Mike Pence for their self-stylings as “God’s Chosen Candidate.” Such reasoning shielded the politician from critical reflection and tempted them toward self-aggrandizement.

It’s not that Romney rejects the notion of a divine mission. He, like many spiritually minded politicians, fuses political positions to religious principles. Indeed, he justified his decision to stand alone from his party in convicting Trump at his first impeachment trial in February 2020, perhaps the culmination of his senate career, as an action rooted in his religious heritage. Romney had always been taught to do what he saw as the right thing, no matter how unpopular, no matter the consequences.

(And the consequences were clear: in a long diary entry in which he weighed the pros and cons of his impeachment vote, he noted the real possibility he might have to move his family from Utah for their safety.)

But Romney’s “Mormon” mission, in the end, isn’t based in predetermined triumph, the messiah narrative of right-wing evangelicals. Rather, it’s framed in a far more Mormon narrative: valiant sacrifice in the face of defeat. Romney’s story is littered with episodes in which his faith brought solace in moments of loss: his two-year mission in France was a period of spiritual growth despite constant rejection; his long-shot senate campaign against Ted Kennedy was, in his wife Ann’s words, his own “Zion’s Camp” (a reference to a failed military campaign by Joseph Smith in 1834); his 2012 presidential run was followed by a Mormon apostle’s blessing that the loss was only the “beginning.” Romney often likened his valiant “losses” to the tough missionary experiences his Mormon apostolic ancestor, Parley Pratt, sometimes encountered.

It’s a story that was quite common to Latter-day Saints in the United States: fervent yearning for, and disciplined labor toward, cultural acceptance, only to be followed by disappointment. The perpetual outsiders. America’s most successful homegrown faith still denied a seat at the table. God’s chosen people are always found in the minority, the valiant few never embraced by the mainstream. It’s a script tailor-made for the saints.

A Mormon of the past

And yet even as Romney comes to represent this archetypal role, many of his fellow congregants are choosing another. Touring Utah as a senate candidate in 2018, Romney struggled to recognize the growing embrace of the far-right in the crowds, including from those of his own faith. (At one event he literally had to hide in a closet to avoid a picture with Ammon Bundy.) This disappointment turned to fear after the January 6, 2021, insurrection, when he spent $5,000 a day to protect his family from constituents who felt angry, acted passionately, and owned guns.

Indeed, a large segment of the LDS community have come to embrace not the figure of the suffering saint, but rather the partisan, macho, and domineering conqueror of White Christian nationalism prevalent among evangelicals. Their hero, of course, is Donald Trump. When Mike Lee, Utah’s other senator—and, as Coppins makes clear, Romney’s rival and foil—compared Trump to “Captain Moroni,” a prominent military figure in the Book of Mormon, he was merely placing a Mormon spin on an evangelical trope: the strong man willing and anxious to do battle. The kind of warrior who never concedes defeat, no matter the electoral results.

A central tenet throughout the book is Romney “reckoning” with his own complicity with these developments. It is important to note, however, just which aspects he regrets, and which ones he leaves unremarked upon. He feels shame for courting Trump’s endorsement in 2012, as well as for embracing right-wing talking points on the campaign trail. (There’s a poignant moment when he was delivering a stump speech in Iowa and realized the topic of his harangue, the supposed “death tax,” was a partisan stand-in for grievance politics rather than substantive policy.)

Yet he never mentions how his fervent calls to repeal Obamacare, support for extensive trickle-down tax cuts, opposition to climate change regulations, and support for Patriot Act-style actions further enabled the Republican Party’s slide to the far-right. This is perhaps because these points are still a core part of the GOP, and he’s instead more interested in the principles that have since been displaced. The martyr image is more appealing than that of accomplice.

Romney’s Mormonism, in the end, may be drawn from the faith’s past, but it no longer appears indicative of its future—or, for that matter, even its present. The modern Mormon march toward American conservatism has required the embrace and appropriation of right-wing evangelical priorities, politics, and even tropes. As a result, Romney, the most prominent Mormon Republican in the nation’s history, now finds himself alienated from large segments of both his political and faith communities.

That such an expulsion came from the same cultural sphere represented by the evangelical leaders who sat in his living room those many years before—the men with whom Romney never felt comfortable working—demonstrates how much can change in a matter of decades.