Spoiler: this recap covers the investigative developments found throughout the three episodes of Murder Among the Mormons, a new documentary released this week by Netflix. A recap of the first episode can be read here, the second here, and an overview essay here.

“It’s not so much what’s genuine and what isn’t, but what people consider is genuine.” -Mark Hofmann

The final episode in Murder Among the Mormons ends with the same interview with which it begins: Shannon Flynn, one of Mark Hofmann’s close friends and confidantes, isolated in an enormous and ornate room, expressing discomfort answering a question concerning Mark Hofmann’s unparalleled forger skills. “Do me a favor,” Flynn pleads in his captivating and hoarse voice, “don’t ask me that.” He doesn’t want to praise the genius of a murderer.

And then he praises him, anyway. As the directors had hoped. And as the viewers had expected.

Americans have a difficult relationship with true crime documentaries. As Saturday Night Live just parodied, we love these murder shows that titillate our always-distracted minds and add excitement to our otherwise mundane lives. But this often comes at the risk of awkwardly celebrating the “genius” of individuals whose actions took the lives of innocent people and introduced trauma to their friends and families.

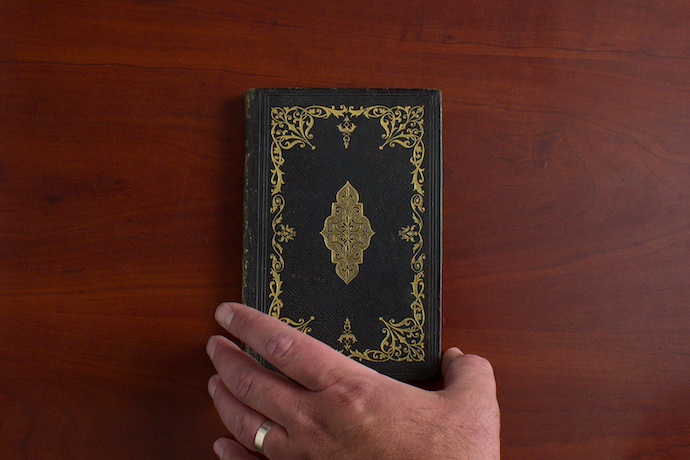

For much of the three episodes, Murder Among the Mormons is exceptionally careful in threading this ethical needle, keeping the tragedy and trauma at the forefront of the discussion. Which was why it’s all the more jarring that the final minutes are so focused on Hofmann himself. They simultaneously reaffirm the generational brilliance with which he created his forgeries, as well as highlight, through photos, that he has now spent over thirty years behind bars, ironically without the use of that very arm that had misled the greatest document experts. As if the final tragedy was the waste of a once-in-a-lifetime talent.

Hofmann’s greatest ability was fooling people. And in the age of QAnon, digital deep fakes, and widespread conspiracy theories, the threat of deception is both real and pressing. “People don’t want to know,” Flynn confesses, hauntingly, in the show’s final moments. He’s talking about how people could overlook Hofmann’s dark side, but the statement could also speak to a general uneasiness with hard truths in general.

The great Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge coined the phrase “suspension of disbelief” to describe how an author—or, one might say, a leader—can convince people to momentarily set aside the implausibility of a story, especially its supernatural elements, in order to appreciate an overall narrative. Such a concept has become a fixture of life, whether it be through entertainment or religion, especially in America. Living in a modern world does not often mean suppressing all irrationality, scholars of secularism have shown us, but rather choosing which irrationalities are tolerable, which forms of unmerited belief are necessary.

The story of Mark Hofmann’s forgeries and murders will forever circle around questions of authenticity and duplicity. The religion at the center of it, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, puts a premium on the certainty of knowledge; the mediums for Hofmann’s deception, antiquitous documents, are supposed to provide finality to historical questions. Hofmann took pleasure in destabilizing both. “He fooled me every single day,” his ex-wife, Dorie Olds, confesses. But what does it mean that so many people believed him? “Does that mean we’re all living lies?” asks Flynn. It’s a big question.

Hofmann, a man who has lost his faith in the religion of his forefathers, takes pleasure in undercutting the certainty of others. “It’s not so much what’s genuine and what isn’t,” he reasons, “but what people consider is genuine.” His primary target isn’t merely the LDS Church, but established knowledge in general. In a postmodern world centered on pluralism, his only God was subjectivity.

And that subjectivity could justify extremes: at one chilling point in his recorded confessions, Hofmann admits that it didn’t matter to him if it was a child who picked up the bomb he left at the Sheets home.

Such a callous—and, indeed, irrational—position shocked many. Perhaps the most powerful moments of the documentary’s conclusion are Hofmann’s family, friends, and associates, especially Olds, Flynn, and Brent Metcalfe, expressing their vulnerability when faced with the enormity of Hofmann’s crimes. How can you be sure of anything when proven so wrong on this?

Near the end of the series, the anti-Mormon critic Sandra Tanner and LDS spokesperson Richard Turley offered competing theological readings of the crisis. To Tanner, Hofmann’s deception proves the fallibility of church leaders and erodes their claims to prophesy; to Turley, free will means that even God’s elect can, and will, be fooled. Debates continue to rage within LDS communities over the particulars of this interpretive spectrum.

But while these are questions intimately tethered to a religious tradition that proclaims new scriptures and prophets, they’re also ever-present with religion in general. America has had no shortage of religious frauds, men and women who have taken advantage of a believer’s suspension of disbelief; conmen and hustlers have repeatedly made fools of those who put trust in our capitalistic system. And while I’ve noted my wish that Murder Among the Mormons would have addressed this broader historical and cultural context, it does at least raise issues that transcend 1980s Utah.

Mormonism is often characterized as the “American Religion,” with good reason. The denomination finally gained a place in the cultural mainstream by championing ‘wholesome’ values at the heart of conservative society. The Mark Hofmann saga, though, demonstrates that the tradition can at times embody some of the more regrettable aspects of the nation’s religious culture, as well.