The distance between being a Jesus Freak and being a Ziggy devotee turned out to be vanishingly small. By accepting “Bowie’s star-crossed glam Christ” (David Fricke1) as My Personal Savior, I was simply substituting one leper messiah for another— the Jesus of Cool for Jesus; a demon lover for a Sweet Savior.

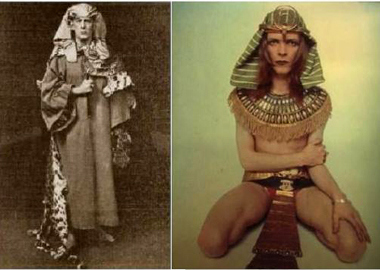

Of course, Bowie was the perfect choice for a surrogate Jesus. More than any other rock star, he invites (demands?) deification. This has partly to do with the messianic sense of destiny that propelled him to rock godhood—a precocious child’s sense of specialness, inflated to Übermenschen extremes by the Nietzsche his older brother Terry introduced him to at an impressionable age. (“I always had a repulsive sort of need to be something more than human,” Bowie confesses in George Tremlett’s David Bowie: Living on the Brink. “I thought, ‘Fuck that, I want to be a Superman.’”2) Becoming Ziggy, onstage and off, from ’72 through ’74, completed his transfiguration into the doomed alien savior of his dreams (a volatile mix of Nietzschean will-to-power fantasies and a martyr complex). His Svengali-like manager’s strategy of limiting media access to the divinity fixed the image of Bowie as aloof and otherworldly in the public mind. By the New Wave era, says Ann Magnuson (a boldfaced name on New York’s downtown scene in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s), Bowie “had turned into something godlike to certain kids who loved the weird, the edgy, the arty, and the glam. By that point, he had become deified.”3

For those with eyes to see it, there had always been a nimbus of religiosity around Bowie, whose metaphoric language is shot through with spiritual symbolism and religious references. A Talmudic study of his lyrics, cross-referenced with a close psychoanalytic reading of his life, reveals an inveterate seeker, hungry for gnosis—the hermetic wisdom that will unriddle the metaphysical questions that nag him.

Bowie’s pilgrimage has taken him through Buddhism to the alien saviors of science fiction and flying-saucer theology and mystical traditions ranging from kabbalism to English magician-scholars such as Aleister Crowley and A.E. Waite to the dimestore occultism of Dion Fortune’s Psychic Self-Defense to the Maronite Christian mysticism of Kahlil Gibran, whose The Prophet, like Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, was a pick-up-line staple at ‘60s love-ins.

Bowie entered his Dharma Bum phase around 1965, after discovering Tibetan Buddhism through Heinrich Harrer’s 1952 book Seven Years in Tibet, a title he lifted for a song on his 1997 album Earthling. (His passion for the Beats, more intellectual trickledown from Terry, had pointed the way to Buddhism, as well.) Immersing himself deeply in Buddhist practice, he studied with the exiled Tibetan lama Chimi Youngdong Rimpoche and seriously considered becoming a monk. Bowie memorialized this period in “Silly Boy Blue” (1966), a psychedelic travelogue starring a Tibetan Buddhist chela (disciple) who flouts the rules of his order. “It’s telling that Bowie’s lyric, while full of Tibetan Buddhist imagery (the references to chelas and overselves, etc.), still sympathizes with the young monk who can’t pay attention, who’s a bit at odds with his culture,” notes Chris O’Leary on his Bowie blog Pushing Ahead of the Dame: David Bowie, Song by Song. “Even in the midst of worship, Bowie has an eye for the heretics.”4

By 1971, Bowie was wading into darker waters. In his majestic hymn to spiritual exhaustion, “Quicksand” (Hunky Dory), he name-checks the notorious occultist and self-styled “Wickedest Man in the World” Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn, a hermetic order with which Crowley was associated, alongside references to Nietzsche, Nazi occultism, and, fleetingly, Tibetan Buddhism.

Later, in 1975-’76, when he was living in L.A. while working on Station to Station (1976), Bowie would burrow much deeper into the occult. Descending into a drug-warped Dark Night of the Soul, he spent days without sleep, sustained by cocaine as he tried to change the channels on his TV telekinetically, scrawled protective magical symbols on the walls, and buttonholed anyone within earshot about the Nazis’ quest for the Holy Grail and the witches who wanted to steal his semen. To create a baby. To sacrifice to Satan.5

In his essay, “Occult Rock,” Greg Taylor discerns traces of Bowie’s occult dabblings on the eponymous title track of Station to Station, where Bowie “references the Kabbalah…with the line ‘one magical movement from Kether to Malkuth,’ talks of ‘flashing no color’ (part of the Eastern occult Tattva system), and also makes a sly tip of the hat to Aleister Crowley’s book of pornographic poems White Stains in the very last line of the song. The album’s art (at least on the CD version) also includes a picture of Bowie sketching the Kabbalistic Tree of Life on the floor.”6

Fascinatingly, the record also includes an achingly beautiful prayer of a song, “Word on a Wing”:

Just because I believe don’t mean I don’t think as well

Don’t have to question everything in heaven or hell…

Lord, I kneel and offer you my word on a wing

And I’m trying hard to fit among your scheme of things

It’s safer than a strange land, but I still care for myself

And I don’t stand in my own light

Lord, lord, my prayer flies like a word on a wing

My prayer flies like a word on a wing

Does my prayer fit in with your scheme of things?

In 1999, Bowie told an audience the song was a product of “the darkest days of my life…I’m sure that it was a call for help.”7 Soaringly emotional, “Word on a Wing” is unabashedly hymn-like, inviting interpretation of Station to Station as a Manichaean struggle between occultism and Christianity.

But it is “Quicksand,” more than any other song, that most eloquently articulates the tension in Bowie’s artistic psyche between belief and disbelief (of the scarifying, Nietzschean sort as well as the soul-sick existentialist variety). “I’m torn between the light and dark,” he sings. “I’m sinking in the quicksand of my thought.” Hedging his bets, he stacks some of his chips on atheism (or at least cynicism), sneering, “Can’t take my eyes from the great salvation/ of bullshit faith,” then makes an about-face, paying lip service to the Buddhism of his hippie days: “If I don’t explain what you ought to know/ You can tell me all about it/ On the next Bardo.” Finally, just to keep his bases covered, he makes an offering at the empty altar of existentialism: “Don’t believe in yourself/ Don’t deceive with belief/ Knowledge comes with death’s release…”

“Questioning my spiritual life has always been germane to what I was writing,” he told an interviewer in 2002. “Always. It’s because I’m not quite an atheist and it worries me. There’s that little bit that holds on: ‘Well, I’m almost an atheist. […] There’s just one niggling thing. Once I shave that off, we’ll be fine and dandy, and there won’t be any questions left.’ It’s either my saving grace or a major problem that I’m going to have to confront.” 8

Part 6: Ziggy, Deconstructed: A fourfold exegesis of glam rock’s sacred text, an album thick with Christological symbolism and biblical allusions.

_________________________

Notes:

1. Quoted in the booklet accompanying the Rykodisc expanded re-release of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1990), unnumbered page.

2. George Tremlett, David Bowie: Living on the Brink, 20.

3. Marc Spitz, Bowie: A Biography (New York, NY: Crown, 2009), 301.

4. Chris O’Leary, “Silly Boy Blue,” Pushing Ahead of the Dame, September 19, 2009, .

5. Marc Spitz, Bowie: A Biography (New York, NY: Crown, 2009), 259-62.

6. Greg Taylor, “Occult Rock,” Daily Grail, December 7, 2009, . See, also, Peter R-Koenig, “The Laughing Gnostic: David Bowie and the Occult.”

7. Nicholas Pegg, The Complete David Bowie (London, UK: Reynolds and Hearn, 2000), 240-43.

8. “David Bowie: ‘That’s the Shock: All Clichés are True” in Anthony DeCurtis, In Other Words: Artists Talk About Life and Work (New York, NY: Hal Leonard, 2005), 263.