How completely de-Christianized and secularized has Western Europe become? Data from the EU tell a tale of radically declining Christian belief and participation. The numbers of those attending Sunday services have tumbled into the single digits, and roughly the same number disavow belief in major Christian doctrines. Despite the political impact of white evangelicals, and the United States’ claim to being exceptional in escaping Western Europe’s radical de-Christianization, Gallup reports that fewer than 50% of Americans declare membership in a church, synagogue, or mosque.

Yet, despite the decline of organized religion, the latest book from French political scientist Olivier Roy, Is Europe Christian?, argues that until quite recently, it could still be said that Europe and America reflected a continued commitment to a secularized version of Christian values, including respect for the dignity of the individual and the institutions enabling such beliefs. Although Roy dedicates most of the book to Western Europe, he sometimes moves seamlessly into examples from the United States, where he seems to believe the differences matter less than one might expect.

The war on the war on Christmas

Since the 1960s, Roy contends, a “new anthropology,” with a morality centered on human “freedom”―including many of the latest cultural trends, including environmentalism, trans-humanism and such―became the heart of the West’s new value system. Despite what might be considered a confusing picture, Roy reads the implications of this exchange of value systems as an indication of secularism’s triumph in the West. The governing values of Europe, in other words, no longer coincide with Christian values. However accurate and profound Roy’s analysis may be, I argue that he may have misread the final elimination of religion for what may also be the emergence of a new religious, though not Christian, consciousness.

These dismal statistics about the decline of Christianity, and the concomitant elevation of human freedom in the West, shed light on the alarm conservative religious activists persistently sound about both secularism and liberalism. Following this script, a revived patriarchy rallies conservative forces against the freedom of women to make choices about their bodies largely by invoking religious authority. Movements supporting same-sex marriage and gender fluidity attract the ire of a right eager to rein in what they see as an insatiable liberalism.

In the mass media, Christian conservatives, such as Fox News’s Laura Ingraham and Sean Hannity, level daily attacks on skeptical liberalism’s ever-expanding search for new frontiers of human choice, especially in the domains of gender and sexuality. There, they rail against the increasing devotion, not only to sex and gender equality and fluidity, but also to fears of catastrophic climate change and New Age dietary practices, such as veganism or vegetarianism.

Laura Ingraham touts her cross pendant.

In place of an ever-expanding liberalism, they reassert a patriarchal order of objective nature that celebrates “Promethean” capitalist dominion and exploitation of the environment. The now-disgraced and “retired” Bill O’Reilly for years grabbed the Fox News bullhorn to denounce the alleged “war on Christmas.”

More recently, over the past few weeks, seeking to allay fears of a COVID-19 pandemic, Sean Hannity effused over the universe being in the care of a provident Divine Creator, while Laura Ingraham, prominently sporting a Four Way Medal cross necklace, claimed that worries over the pandemic was simply “a new pathway for hitting President Trump.” (Of course, that was all before the president reversed course and these commentators fell in line behind him.)

In the political domain, Christian nationalists also never tire of boasting that the nation’s virtues rest on allegedly Christian or biblical foundations. Christian historical mythmakers, such as David Barton, claim that the United States is a “Christian nation,” liberally cut-and-pasting quotes and facts to make their case. Christian nationalists calculate that historical revelations will insure the present ability of religious corporations to feed freely at the public trough. In their Christian nation nothing is more American than Christian private schools enjoying public funding. No Muslim schools need apply.

In their view we should also accede to the exemptions sought by Christian corporate entities like Hobby Lobby who abuse the constitutional guarantee of religious liberty so they don’t have to provide the comprehensive health care for women that they oppose.

By asserting their rights to such religious exemptions and accommodations, Christian nationalists believe they deal yet another blow to noxious secularism by shoring up the privileged place of religion in the public square. Whether it be Fox News celebrities or religious corporations, they see their acts as part of a larger movement to roll back the tide of secularism. Religion belongs in the public square―indeed owns a franchise there―even if that franchise functions no differently than a profane political party.

Who owns cultural symbols?

Imagine the surprise, then, of Christian nationalists, if Olivier Roy is right in his implied critique of the likes of Hannity, Ingraham, and the rest of the Christian nationalists? Namely, what if many of these and similar assertions of religion in the public square actually hasten and deepen secularization?

This ambitious critique of secularism makes Roy’s book far more radical than its title would have one believe. Roy wants to show how the very assertion of Europe’s Christian foundations itself can aid its de-Christianization; that well-meaning, if ill-conceived, attempts to re-sacralize modern societies, often just result in the deepening of that secularization.

Let me explain. Bill O’Reilly may have imagined that his campaign against the “war on Christmas” would ‘put Christ back into Christmas’ and restore awareness of the ‘reason for the season.’ But, it does no such thing. At most, O’Reilly just promoted a bullying cultural identity of the god-fearing GOP “us” against secular-humanist Democrat “them.”

Or, again, is this not just more identity flashing; more “identitarian Christianity,” courtesy of the mute frozen images of the thriving Sacred Heart, St. Joseph, St. Christopher, and Miraculous medal industry that Roy writes about? These guys are on my team. Who’s on your team? Thus, Roy, in effect, indicts Hannity, O’Reilly, Ingraham and other Christian “identitarians” as religious frauds. In reality, they’re acting out an odd performance of cultural identity, more than they’re doing anything prophetic to revive the sacred in a profane world. In Roy’s words:

Seeing the return of Christian cultural symbols to public space as the starting point to win back souls is absurd. Those who promote it care little for the teachings of the Church; their intentions pertain more to folklore, entertainment, spectacle and exploitation. Paradoxically, bringing back Christian symbols actually helps to secularize religion.

But Roy’s paradoxical critique of Christian identitarians and nationalists goes beyond exposing the shallow piety of media talking heads. European courts have recently been challenged by Christian nationalists, Muslims, and others to weigh in on cases which seem at first outside their legitimate commissions. Prominent here are blasphemy cases, the most notorious of which concern Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses or the Danish cartoons of Muhammed.

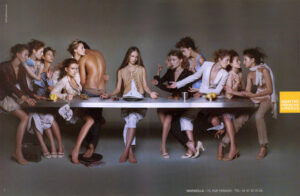

Problematically, although European courts don’t officially recognize the legal standing of the sacred/profane distinction, in their attempts to keep social peace they have sometimes contradicted their mandates by wading into these waters. In 2005, a Catholic group in France appealed for a judgment by the Court of Cassation of “blasphemy” against the fashion firm, Marithé et François Girbaud for a lewd promotional adaptation of Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper.” The Catholic plaintiffs charged that the irreverent commercial display violently assaulted the innermost sacred beliefs regarding Christ’s institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper.

Like O’Reilly’s implicit claim that Christmas should only be seen as a sacred occasion, not as a cultural one, these Catholics claimed exclusive ownership of the Da Vinci painting as an inalienably sacred object. They refused to concede the equal validity of the painting’s popular cultural value. In an apparent effort to push back against such profane cultural uses of what these Catholics wished to define as inalienably sacred, they simply insisted that any profane use of such sacred objects constituted a legally actionable attack on their god.

In its judgment, however, the court surprisingly gave the Catholic plaintiffs partial satisfaction. The ad, the court said, “’does away with the whole tragic nature … inherent in the first event of the Passion.’” In doing so, it at least partially conceded the legitimacy of its jurisdiction over cases of blasphemy. But the court didn’t then follow through and penalize the advertising agency for an offense against Christ. Instead, it ruled that the ad threatened to damage secular social peace.

Thus even though the Catholic group ‘won’ its suit in some sense, the court ruled on secular, not religious, grounds. This attempt to sanctify the legal domain by ruling in the matter of offense to the sacred―blasphemy―became instead the profane offense of “damages awarded for the suffering of individuals.” So what seemed to be a victory against secularization only deepened secularization since the court quietly passed over blasphemy in the all-important penalty phase of its ruling.

Wine-and-pork Christianity

One supremely inconvenient fact seems to be throwing the matter of secularization further into confusion in Europe―the increasing presence of Muslims. Roy claims Islam’s presence not only reshapes religion in Europe―however subtly―but it even forces a rethinking of Christianity, and not always in legitimate ways.

To demonstrate, Roy mentions a French group that organizes ‘Christian’ identity street festivals, featuring the consumption of French wines and pork sausages. While on the surface, these gatherings are meant to foster identity, they do so indirectly―by effectively excluding Jews and Muslims. However conspicuously ‘Christian’ identitarian groups claim to be, such efforts are clearly more concerned with cultural exclusiveness than with any commitment to the Christian Gospels. This isn’t the Christianity of religion, but the stuff of uniforms, badges, flags or other empty―and notably secular―signifiers of difference.

Other identitarian actions by Christians, specifically against Islam, have also produced unintended secularizing results. In an effort to thwart the growth of Islam in Europe, identitarian Christians sometimes seek to impose bans against the Muslim headscarf. But such attempts to thwart Islam in favor of protecting the Catholic nature of France (though often hiding behind the fig leaf of a less-bigoted laïcité) have had unintended consequences. In order to abide by secular laws of equal treatment to all religions, it has led to a wholesale banning of religious symbols by Jews and Christians alike, thus further secularizing the public square.

Or consider how the recent banning of minarets in Switzerland has further secularized Christianity in that country. In the spirit of religious tolerance, the Swiss don’t object to the building of mosques as such, but only to the foreign-ness of them; to the fact that they don’t fit into Switzerland’s Christian character. Thus, building ‘Swiss-looking’ mosques (cuckoo-clock tower minarets?) would be fine because they’d conform to Swiss aesthetics ―even though, ironically, promoting Islam in the process.

Mocking this misguided attempt to assert Switzerland’s Christian character, Roy ridicules the whole effort by suggesting that the Swiss could satisfy their desire for a properly acculturated Islam by having the call to prayer yodeled, too! Thus, those misguidedly wishing to protect Christianity by forbidding the construction of minarets, in effect, have furthered secular trends by reducing religious difference to cultural aesthetics.

Despite the ostentatious piety of the Fox News folks and the political muscle of the Christian identitarian nationalists, Roy sees both in sharp contrast to the ‘real thing.’ These are the new apolitical “Catholic Revivalist” groups of committed, often lay-led, communities of personal faith and “direct relationship to God.”

Formed as extra-territorial entities linked solely to the “pontifical right,” they catch Benedict XVI’s spirit of the ‘small church,’ alienated from an increasingly de-Christianized European secular culture. These revival movements include various “tradismatics” (traditionalist and charismatic) communities, the Alpha course group, the Sant’Egidio movement, the Community of Saint-Martin, Focolare Movement, Emmanuel Community. They all see the world as “pagan, rather than merely profane,” and see themselves as wholly built around religion, seeking in the end to oppose Europe’s anti-Christian enemies―both secular liberalism and Islam―in a lonely effort to reconvert Europe.

A religion without a name?

Roy’s nuanced complicating of the issue of Europe’s supposed Christian character is deeply welcome. Giving the lie to noisy, self-negating attempts to promote Christianity in the public square helps us appreciate the significance of the genuine attempts of prophetic groups to affect religious renewal in Europe. Appearances can thus be radically deceiving.

Nonetheless, Roy’s conception of religion (and its elimination) seem somewhat narrow. I mean, when he judges that elements of the “new anthropology”―liberalism’s non-theistic beliefs in personal freedom, sex/gender equality and fluidity, care for the planet, reverence for nature, non-violence, veganism/vegetarianism, conviction of the unity of living beings, and such―are secular, one wonders what notion of religion is at work, here? Certainly, it’s not religion as reflected in Abrahamic conceptions of religion as the dualistic, patriarchal, sin/guilt dominionism expressed in the Book of Genesis.

But the values of the “new anthropology” do recall elements of the religious syndrome developed among the Buddhists, Jains and other nāstika dissenters from Brahminism in the 6th century BCE Ganges Valley. At the moment, this “new anthropology” of which Roy speaks doesn’t seem to have coalesced into the kinds of coherent Eastern religious movements mentioned above. Perhaps it never will. But because we hardly understand how religions come to be, we can’t really say with any degree of conviction that this new anthropology is either merely a symptom of the final victory of profane secularism or the first shoots of a new―although not Christian―growth of the sacred, and thus a new chapter in the history of religion in Europe itself.