Is there anything interesting in the latest report from PRRI on Christian nationalism in the US? Only the best description of the American political landscape in quite some time.

But let’s understand why. PRRI asked respondents in their American Values Atlas survey to what extent they agreed with a series of statements related to Christian nationalism:

- The U.S. government should declare America a Christian nation.

- U.S. laws should be based on Christian values.

- If the U.S. moves away from our Christian foundations, we will not have a country anymore.

- Being Christian is an important part of being truly American.

- God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society.

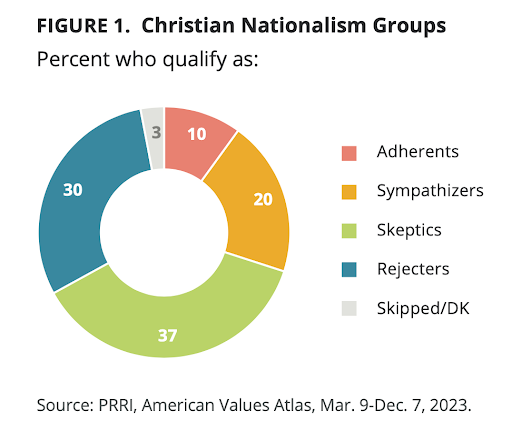

Depending on their level of agreement, respondents were sorted into four categories: Christian Nationalism Adherents, Sympathizers, Skeptics and Rejecters. As you can see from the graph below, Adherents and Sympathizers make up a relatively small slice of Americans. Two-thirds of US citizens reject Christian nationalist propositions in part or whole.

Adherents and Sympathizers are pretty much who you would expect them to be. They’re more likely to be conservative, White, evangelical, Republican and supportive of Donald Trump. They’re also much more likely to be frequent church attenders, have less than a college education, and prefer partisan outlets such as One America News Network or Newsmax.

More disturbing, they’re also the most likely to agree with ideas like “There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders” or “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” (Oddly, Hispanics are more likely than Whites to hold those views.) Their issue priorities are guns and immigration: They like the first, not the second.

Skeptics and Rejecters are also much who you would expect them to be: Educated, liberal, loosely attached to Christianity or from another (or no) tradition altogether.

Intuitively, this lines up with secular descriptions of the political landscape. Hardcore conservative supporters of Trump are a very small group. Surrounding them is a larger group of traditionalists. Together, those groups make up a majority (55%) of all Republicans. The vast majority of both Democratic voters (83%) and Independents (73%) are Skeptics or Rejecters. The 2024 election will be largely contested over the few Republicans suspicious of Christian nationalism and Independents friendly to it.

You can literally map out these differences. Blue states have very low levels of support for Christian nationalism. Red states are just the opposite. And the battleground states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, and Wisconsin? They’re all right around the national average.

Those numbers are not destiny, however. Conservative Utah has low levels of agreement with Christian nationalism, at just 28%. Meanwhile its solidly Democratic neighbor New Mexico is a bit higher, at 32%.

Still, the results are significant for understanding the political scene today. Christian nationalism should not be ignored or downplayed, but at the same time the segment of the population that embraces it is punching above its weight. Two states—Mississippi and North Dakota—reach 50% support, and only a handful land in the 40s. The rest of the nation ranges from the teens to the mid-30s. That’s a significant minority, to be sure, but a minority all the same.

That means the election need not be played out on Christian nationalist terms. Voters may be less supportive of immigration than they’ve been before, but Democrats are otherwise solidly aligned with the values of the majority of Americans.

That Christian nationalists are in a solid minority in places like Ohio, Texas, or Florida also demonstrates the perilous position of hard-right regimes in such states. Were it not for gerrymandering and other anti-democratic tactics, their agenda would be firmly rejected. To put things another way: there are a lot more places that could be opened up as swing states on the basis of rejecting Christian nationalism than the other way around.

Last, it may be the case that, much as it was before the Civil War, Americans are facing a theological reckoning as much as a political crisis. On the one side is an aging, dwindling group that asserts that its understanding of God blesses and endorses a traditionalist social order. On the other is a more diverse, more secular group suspicious of authoritarian faith and the ways in which invocations of religious values privilege inequality and repression. The 2024 campaign will be finally a decision about which of these views should dominate and which candidate gives the best expression to authentic American values.