Last Sunday, I saw a few new faces at my church in Beacon, New York. They came not because of a sudden call to Presbyterianism, but to mourn the death of Pete Seeger, the town’s most beloved resident.

As you may have read in every single obituary, the revolutionary folk singer lived in this Hudson Valley town for forty years, on the side of a mountain, in a home he built himself. Everyone in Beacon is indebted to him for one reason or another, be it the cleanliness of the Hudson River, the opening of the town’s first live music venue, or the grant in his name that gives us free entry to the local museum. In the two years I’ve lived here, I’ve seen the way that Seeger shaped this place: not single-handedly, but by inspiring others to join hands. He made us feel like change was both possible and necessary.

And now that he’s gone, the people of Beacon must figure out how to carry on his legacy. One peculiar thing I’ve noticed is that people struggle not to beatify the singer. It may be a losing battle; the phrase “patron saint of Beacon” has commonly come to describe him. But it’s not who Pete was.

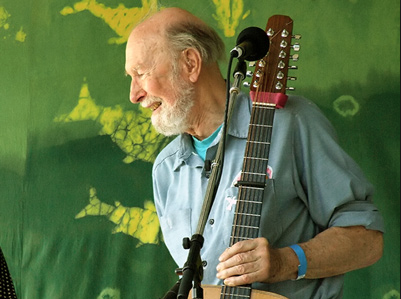

Seeger was, first and foremost, a man of the people. His songs were his message, and they were intended to bring people together—not so he could lead them, but so they could lift each other up. He did not discriminate between different kinds of people. He wanted all of us to sing together. Even in his final years, he’d play Carnegie Hall one week, then sing with local schoolchildren the next. As he told the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955, prior to being blacklisted:

“I am saying voluntarily that I have sung for almost every religious group in the country, from Jewish and Catholic, and Presbyterian and Holy Rollers and Revival Churches, and I do this voluntarily. I have sung for many, many different groups—and it is hard for perhaps one person to believe, I was looking back over the twenty years or so that I have sung around these forty-eight states, that I have sung in so many different places.”

It’s hard not to idealize a man who hewed so closely to his own ideals for 94 years. But Pete wasn’t interested in being a saint. When Bob Dylan referred to him as such, he actually got upset.

“What a terrible thing to call someone,” Seeger told USA Today in 2009. “I’ve made a lot of foolish mistakes over the years.”

One of my favorite mischievous stories about Seeger comes from a college friend, who sneaked into a high-roller benefit at which the singer was appearing. When the bouncer tried to kick him out, Pete interceded—then told my friend he was now responsible for bringing him drinks all night. I love that Seeger couldn’t bear to see someone excluded from a party, but I also love that he dealt with the situation by appointing my friend his personal cocktail servant.

Another less-than-saintly notion about Seeger—a well-documented one—is that he frequently left his family behind, or put them in danger, in the name of activism. His incredible wife Toshi, who raised their three children, used to joke: “If only Pete had been chasing women, rather than causes, I could have left him.”

(When someone dedicates his life to “the people,” it’s the people closest to him who must often suffer in silence. Is this what’s happening in Matthew 12, when Jesus refuses to speak to his own mother, saying his disciples are now his family? But I digress.)

None of these things, of course, dilute the purity of Seeger’s message. In my church last Sunday, the service was infused with people’s memories of the man, the songs he sang, and the lessons he taught. I wonder how many other Hudson Valley churches held informal Seeger services that day. A lot of them, I’m guessing—which is interesting, since Seeger always denied being a man of faith.

“I think to be asked about his religion, or about his beliefs, or about his political thoughts, was such an insult to him, because it was insulting to every American,” Seeger’s protege Arlo Guthrie said in a recent interview. “He had a way of taking these personal events in his life and moving them forward so that they included everyone.”

Officially, Seeger was a Unitarian Universalist, though in a 2006 Beliefnet interview, he admitted that he joined up in order to use their New York City rehearsal space. But despite his waffling about all things religion, there is a deeply spiritual element in Seeger’s work, whether it’s “If I Had a Hammer” or “Turn, Turn, Turn” (which he adapted from Ecclesiastes).

“[I used to say] I was an atheist,” Seeger told Beliefnet. “Now I say, it’s all according to your definition of God. According to my definition of God, I’m not an atheist. Because I think God is everything. Whenever I open my eyes I’m looking at God. Whenever I’m listening to something I’m listening to God…I’ve had preachers of the gospel, Presbyterians and Methodists, saying, ‘Pete, I feel that you are a very spiritual person.’ And maybe I am. I feel strongly that I’m trying to raise people’s spirits to get together.”

Throughout his life, Seeger frequently played music at houses of worship of every denomination. As the pastor at my own church deftly put it: Pete Seeger had mixed feelings about organized religion, but he had strong feelings about organizing. He knew the power of joining people together in song. His hope for people of faith was that they’d take it one step further.

“I’m urging all religions to at least tolerate talking with each other, even though it’s hard to speak without getting angry because they feel that some beliefs are so bad, others’ beliefs,” he said. “But I think one of the saving things of the world would be getting people to be willing to talk to each other, even though they think they are representing the devil incarnate.”

One of Seeger’s final days in Beacon was Martin Luther King Day, during which all the town’s religious congregations united in a parade and chorus to honor the civil rights leader. It was Pete’s idea. He was too sick to attend, but he was thrilled that it happened.

It’s interesting that the “organized” part of organized religion gets such a bad rap. It has come to seem corporate, perhaps even militant: the church rising up like an army to assimilate nonbelievers. But for Seeger, “organize” was a magical word. It was the notion of different kinds of people coming together for one cause. Organizing, for Pete, was the power to change the world. He saw that potential in a lot of places. And one of them was churches.

Of course, he also had a sense of humor about the whole thing.

On the day of Seeger’s public memorial, I attended, instead, a benefit concert for Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America. It was literally the place where Pete had planned to be that day. He never stopped pursuing justice. He never stopped singing.

Which is exactly why we shouldn’t turn Pete Seeger into a saint. Any statue erected in his honor would be a bad likeness, because Pete was never still for that long. His legacy doesn’t belong on plaques or in platitudes. It belongs in action, in groups of people coming together, and in a man walking into a church for the first time, realizing he didn’t want to be alone that day.