When celebrity chef Dan Barber and author Michael Pollan, both Jewish, appeared together at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan in January, 2008 they each gleefully opened their remarks before the heavily Jewish audience with a personal pig story. Food writer Sara Kate Gillingham-Ryan even described the event as including “many a joke about Jewish boys liking artisanal pork.”

Indeed. Pollan devotes an entire chapter of his most recent project, Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation (Penguin Press HC, 2013)—more than a quarter of the book—to whole hog barbecue, reveling in details about learning from the pit masters of North Carolina, perfecting the technique of crackling (making crispy pig skin), and inaugurating his own, now-annual, pig roast tradition in the front-yard fire pit.

Pollan is hardly the only Jewish foodie with a pig fetish, though he’s certainly the most well known. Last year amateur chef Wesley Klein founded Baconery, an Upper West Side bakery featuring—what else?—bacon in every product, including sandwiches named after popular pig characters like Miss Piggy, Wilbur, Porky Pig, and Babe. And it was from food and fly-fishing writer Peter Kaminsky, author of Pig Perfect, that renowned North Carolina barbecue pitmaster Ed Mitchell (with whom Pollan “apprenticed”) learned about the traditional pig breeds nearly eliminated by commercial industrialization. (In his loving, obsessive rhapsody to things porcine Kaminsky called himself a “ham idolater” and owned his agent’s description of him as a “professional hamthropologist.”)

Then there’s Ari Stern, owner of Culturefix, a bar and gallery on the Lower East Side, whose trendy monthly supper club held an event called “Passover for Goyim, A Very Traif Seder Plate.”

The traditional ritual centerpiece at this event—the seder plate whose five (or six) foods recall the divine delivery of the Israelites from Egypt—boasted all-treyf foods, including, of course, several varieties of pig meat. Advertising for the event featured a cartoon of a yarmulke-wearing pig stamped with a large six-pointed star and, toward the rump, the kosher certification symbol of the Orthodox Union, “OU.” The image is eerily reminiscent of European anti-Jewish propaganda used, ironically, to represent alleged Jewish hypocrisy.

Jews and Pigs

It’s widely known that the pig is the most taboo food in Jewish culture; such is its abhorrence that even many non-religious Jews avoid it. Ancient Rabbinic law highlighted the pig’s singularity by prohibiting Jews from deriving any benefit at all from it—including raising or selling it, or using any part of its body for any purpose.

Though largely couched in lofty or insouciant foodie rhetoric, eating and enjoying this forbidden food is clearly a turn-on for some Jews; transgression just sweetens the meat. Kaminsky documents the moment he “became conscious of my soul-to-soul pork connection,” while Pollan muses that “There is something life-altering about pork crackling.”

How things change. In medieval Iberian cultures, under the shadow of the Inquisitions, to refuse to eat pig would mark one as a Jew. Since many thousands had been forcibly converted, serving pig was an easy way to check their loyalty as freshly-minted Christians. Dire consequences usually hounded conversos who refused, leading many to eat pig simply to save their skin; the choice to eat pig might literally be a matter of life and death.

The denigration and exclusion of those who refused to eat pig—Jews and Muslims—typified life in rural Europe, as outlined in The Singular Beast (Columbia U. Press, 1999), a powerful, disturbing, and at times gruesome, study by French anthropologist Claudine Fabre-Vassas. Body parts of the pig were given Jewish names; Jews were called pigs (conversos were called “porkchops”); pigs served as stand-ins for Jews in Easter processions; Judas in Passion plays would be sprinkled with pig blood; ritual holiday meals had suckling pigs stand in for Christ; and people held children before baptism to be piglets, devils or little Jews who grew “pig’s teeth” and “Jew hair.”

A Burgundian ditty summed it all up:

The more we enjoy the piglet / The better Catholics we become.

The pig as identity-marker continues more subtly to this day in places like urban France, where Jews and Muslims who don’t eat pig are often still seen as outsiders, as discussed by French political scientist Pierre Birnbaum in his latest book, La République et le Cochon (The Republic and the Pig). English Food writer Jane Grigson reiterates such othering when asserting that “It could be said that European civilization… [has] been founded on the pig. […] There has been prejudice against him, but those peoples… who have disliked the pig and insist he is unclean eating, are rationalizing their own descent and past history.”

Jewish foodies have turned this history on its head, advocating the glories and wonders of pig and its meat; how nothing is quite like it, not lamb, not goat, not goose, nothing. Of course, this love affair with pigmeat can easily be seen as merely the latest chapter of modern Jews thinking they are liberating themselves from the shackles of an irrational rabbinic tyranny based on outmoded laws. From another perspective, an observer might conclude that eating pig proves better than just about anything that one belongs to the dominant (Christian) majority, or that one has left Judaism (and the whole business of superstitious faith) behind. As Wesley Klein says, half-jokingly, “[my bacon obsession] only proves that Baconery welcomes customers of all faiths.” Call it porcine supersessionism.

To a non-believing Jew or one who chooses not to observe the laws of kashrut, of keeping kosher, eating pig might seem no more transgressive than flipping a light switch on sabbath. So perhaps the expectation that even secular, or so-called “cultural” Jews, maintain respect for the prohibition of pig is to harp on what is, from that perspective, a non-issue. It’s clear that Pollan and his peers cook, write and engage as Americans, as universalists, each an everyman. They rarely discuss their Jewish identity in their writing or public speaking, except when addressing Jewish audiences.

Food, Judaism, Laws

Throughout his writing Pollan insists, correctly, that non-Western and non-industrialized cultures bear great wisdom about community and healthy eating, though this conviction does not, evidently, extend to Judaism. The norms of other cultures aim to (or successfully do) protect health, while the laws of kashrut are, says Pollan, “probably designed more to enforce group identity than to protect health.”

Pollan makes his lack of regard for religious Judaism clear in his writing, frequently discussing the pet pig (which he named “Kosher”) given to him by his father, and recounting his kashrut-observant brother-in-law’s contribution of a “hemispheric steel frame” to his annual pig roast. This clearly signifies for Pollan a kind of triumph: the mindful pig roast trumping superstitious religion, bringing people together rather than dividing them.

Pollan does admit to some reluctance when cooking the ancient, and “radically unkosher,” Roman dish, maiale al latte. “There does seem something slightly perverse about cooking [pork] in milk,” he confesses, though he’s appeased by the fact that even the rabbis themselves categorized the taboo on mixing milk and meat as a law “for which there is no obvious explanation.”

To the rabbis this inexplicability meant one should obey the commandment out of reverence and humility before that which escapes our understanding; for Pollan, since this ban lacks a known bio-chemical hazard, it means dispensing with the commandment altogether.

This past April, discussing whole-hog barbecuing on the Leonard Lopate show, Pollan opined that because the various cuts of the pig are mixed together in the resulting sandwich, the process is “very democratic.” Perhaps thinking of his multiethnic New York audience, Lopate, who also happens to be Jewish, pointed out that not everyone eats pig, which prompted the following exchange:

Pollan: I think, you know, that we need to rethink the kosher rules and I think there is a place for pork in the kosher rules…To the extent that the kosher rules are about eating ethically, I think eating pig can be a very ethical kind of eating.

Lopate: Only two or three thousand years of tradition out the window.

Food, Culture, Religion, Health

Pollan’s breezy dismissal of kashrut as a set of arbitrary rules imposed for the sake of reinforcing an exclusive identity represents an unfortunate flaw in his vision for an ethical and rich food culture.

Pollan argues that the main problem of the contemporary American diet—that it’s unhealthy for both people and planet—is essentially a problem of culture. Yet his spot-on critique of the corporate “science” that deconstructs food in order to manufacture profitable “edible food-like substances”—isolating single ingredients, artificially overstimulating natural cravings—also applies to his own American, libertarian and bourgeois selection of isolated “dishes” from the cultural buffet table.

Pollan seeks to bring about a return to what industrialization and commercialization have nearly destroyed, namely “deeply rooted traditions surrounding food and eating.” He acknowledges that “as the sway of tradition in our eating decisions weakens”—by which he means “the cultural norms and rituals that used to allow people to eat meat without agonizing about it”—“habits we once took for granted are thrown up in the air.” But once again, while Pollan justifiably admires “indigenous” consumption patterns, he turns his back on the approaches of his own culture, Judaism.

The appearance of religious vocabulary in Pollan’s writing reveals that eating (right) is believing. Stories of conversion experiences are sprinkled throughout his books: non-cooks turned into cooks by eating a single, wondrous meal; white-flour bakers made whole-grain zealots from biting into a single loaf of great whole wheat bread, and so on. The first line of Cooked and its first section on pig barbecue evokes “The divine scent of wood smoke and roasting pig.” Pollan witnesses the innovative way Polyface Farms uses pigs to aerate the cow-barn bed of manure and other ingredients into rich compost—by placing corn among the mix so that the pigs delightedly root around for it, opening up and stirring the whole shebang—which he describes as “a miracle of transubstantiation.”

Likewise, the farm’s compost pile of unused chicken parts carries “redemptive promise”; monoculture is “the original sin from which almost every other problem of our food system flows”; and to brew your own beer every once in a while “becomes, among other things, a form of observance, a weekend ritual of remembrance” of interconnectedness. Such language rhetorically transforms sagacious farming and mindful eating into sacred wonder-working while more traditional religion sparks deep ambivalence, often arising as a negative counterpoint.

Pollan yearns for traditional food cultures, yet he reflects the collective repulsion of so many moderns toward tradition. With some justification Pollan lambasts the transcendentalist, utopian, anti-naturalist “Puritanism” of certain animal rights arguments that predation among living creatures in nature is an “intrinsic evil,” a view that goes back at least to Isaiah 11:6-7 (the lion and the lamb, etc).

So-called “nutritionism,” which obsesses about “invisible and therefore slightly mysterious” entities rather than food, “is a quasireligious idea, suggesting the visible world is not the one that really matters, which implies the need for a priesthood.” Pollan is “inclined to agree with the French, who gaze upon any personal dietary prohibition as bad manners.”

While lamenting repeatedly the decline of eaters’ gratitude and the saying of grace or similar blessings at meals, Pollan does not make blessings, even at the “perfect meal” with which Omnivore’s Dilemma culminates, which has been prepared with extreme arduousness and so laden with consciousness that he calls it a “ritual.”

Yet despite the liberal use of spiritual vocabulary, the potpourri of concerns that move foodies like Pollan often reveal a materialistic and scientistic orientation. Chef Dan Barber proclaimed in an interview: “I believe in something that, from A to Z, is rooted in Hedonism.” He resists the idea that the deep pleasures of conscious eating derive from anything called the “spiritual discipline” of conscious food preparation. Echoing this distaste for the spiritual, the founders of the Slow Food movement (who are not Jewish) dedicated their collective efforts to “a firm defense of quiet material pleasure” as “the only way to oppose the universal folly of Fast Life” (my emphasis). For his part, while Pollan concedes that “shared meals are about much more than fueling bodies,” he’s careful to exclude any spiritual element, writing that they’re “uniquely human institutions where our species developed language and this thing we call culture.”

However vital they may be, the social and ecological relationships built and strengthened through and around food still leave something missing. Almost every traditional cuisine that Pollan lauds developed as a strand within the holistic web of a traditional nature-culture that included supernature: mind, wisdom, spirit, cosmology. Practice emanated from this holism, yet Pollan and his peers have internalized the Western distaste for significant parts of it, a distaste that can, ironically, be read as itself part of the very process of modernization that Pollan decries.

Culture, Cosmos, Commandment and Resistance

Pollan may want his culture “rational,” but culture is not modern science—nor should it be. As Wittgenstein understood, meaning is made by people and cultures, rather than found through some kind of objective measurement. The various diets Pollan upholds as beneficial—Inuit, Samoan, etc.—arise out of, and are steeped in, complex and rich culturally specific worldviews, cosmologies, practices and beliefs, some of which may well seem “not rational.” This stew can be broken down into discrete elements, but at great cost precisely to the forces of cohesiveness that can make wisdom traditions powerful and beneficial in the first place.

Just as the frequent combination of eating tomatoes with olive oil has now been understood by science as a way to ease digestion of the lycopene-rich tomato because it is oil-soluble, as Pollan learned, cultures, too, come subtly and tightly interwoven in ways that “rationalism” continues to miss. “To make food choices more scientific is to empty them of their ethnic content and history,” he writes. But while Pollan wants us to eat more ethnically, learn our culinary history and erase the worst of modernist agricide, he proceeds as if one can extract the effective ingredients from a particular culture and not destroy its overall efficacy.

While acknowledging that “food cultures are embedded in societies and economies and ecologies,” and that “traditional diets are more than the sum of their food parts,” Pollan doesn’t appear to extend the same respect to cultures as a whole. He writes that American food corporations are “systematically and deliberately undermining traditional food cultures everywhere,” but misses the bigger picture that industrial capitalism in general undermines traditional cultures as a whole everywhere, and that this is why their food cultures collapse.

“How to Eat,” the final section of 2009’s Food Rules, would amuse or perhaps depress any observant Jew—or nearly any individual living in a traditional culture for that matter. Having informed readers of what and what not to eat Pollan offers suggestions regarding:

something a bit more elusive […] the set of manners, eating habits, taboos, and unspoken guidelines that together govern a person’s (and a culture’s) relationship to food and eating.

Some of his suggestions: eating only at a table, eating only with other people, taking a moment to meditate on where your food comes from before consuming it, or eating treats only on weekends. Writing for people he assumes are very much like himself—secular and disconnected from their backgrounds or any particular tradition—Pollan attempts to add a dash of mindfulness and ritualization to the materiality of their food.

One can only think of Pollan’s complaints about refined white flour, a nutritious natural product that’s been so heavily processed it’s not only non-nutritious but downright hazardous to the health. The industrial solution has been to toss back in a few of the eliminated nutrients on the production line, like iron and B vitamins, in a minimal gesture whose efficaciousness remains doubtful—which is essentially what Pollan does with culture.

Modernity has decimated traditional cultures, made them undesirable. Faced with the erosion of mindfulness and wisdom embodied in ritualizing practices or sacralized boundaries, Pollan tosses back in the cultural equivalent of some iron and B vitamins hoping this will somehow restore balance. He complains that to bake great bread with whole wheat flour in the face of the near-total monopoly of white flour and the industrial, commercial apparatus that supports it, he needs not just a “better recipe,” but “a whole different civilization.” How very true, but not merely in regard to material ingredients.

Fortunately, not all of those alternative civilizations have been starved out of existence. Some continue to exist, if tenuously and largely on the margins, and each of the traditional groups lauded by Pollan as living without the Western Diet and its diseases believed, and believes in, some version of what moderns consider a mythological cosmos: animated, divine. They haven’t succumbed (or have succumbed less) to rationalism, to the “logic” of industrialism and global markets.

While many factors determine the fate of a civilization and culture, likely there is a correlation between the cohesiveness, depth and vitality of a way of life based on some version of metaphysics and the ability to resist über-rationalist, corporate modernity; think about various Native Americans, the Amish, Hasidim, hippies—even the Zapatistas—and so many more. Of course, all these cannot be collapsed into some homogenous thing called “spirituality,” “metaphysics” or “religion”; as always, the assessment of religious traditions and metaphysical worldviews constitutes an essentially political determination.

As is the case in the wider environmental movement, many people and organizations concerned with agro-food questions understand metaphysical or spiritual matters to be part of the holism they address and in which they live.

In the United States the thinking of Wendell Berry and Wes Jackson make prime examples, while educator, chef and restauranteur Alice Waters includes the spiritual when describing her own discovery of good, healthy food and eating (while carefully distinguishing these sensual pleasures from mere hedonism), and biodynamic farmers, whose movement grew out of the explicitly spiritual work of Rudolph Steiner, are quite comfortable with spiritual, cosmological language.

Scholar Melissa Caldwell points out that in Russia, “‘natural foods’ philosophies represent the natural environment as a source of sociability and spirituality,” and Russians feel nature “not only produces but also nourishes and protects the Russian nation.” Personal gardening is considered “an activity done ‘for the soul.’”

In Nepal, conservation of nutritionally- and ecologically-beneficial native rice varieties, and therefore of rice diversity as a whole, is aided by the fact, as reported by Nepalese farmers, that some rice “landraces have identifiable socio-cultural and religious use values i.e., landraces used in make special dishes for offering to deities,” while modern varieties, the only kind promoted by the government, “are considered ‘impure’ for socio-cultural and religious ceremonies.”

Faced with a soaring rate of Diabetes caused by the abandonment of traditional foods for “white” food products, the Tohono O’odham of the Sonora Desert have organized through communal institutions to support a return to their nearly extinct thousand-year-old former diet, writes Marcello di Cintio in Gastronomica. This so-far successful process, an exemplary case study of the kind of resistance to the Western diet that Pollan would admire, inevitably includes a reclamation of their culture, which:

connects the emotional and spiritual lives of the O’odham with the landscape they maintain, the spirits they worship, and the foods they gather and grow. The [traditional way] teaches the songs O’odham sing to inspire their beans and corn to grow. It gives directions for the saguaro wine ceremony, the O’odham’s new-year ritual that “sings down the rain.”

I am not arguing that we must preserve every ritual or tradition. But a solely materialistic food movement that shares the modern proclivity to dispense with anything cultural it does not understand, likely does not understand what it is destroying.

Paradoxically, in being quick to eschew powerful imperatives like sacred prohibitions or ritual, it would also be ignoring the urgings of one of its own sources of inspiration, ecology, as in Aldo Leopold’s oft-quoted dictum: “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.” Italian sociologist and psychologist Alberto Melucci exhorts with greater explicitness against thinking that tinkering even offers much hope. Our global ecological crises, he maintains, show “that the key to survival is no longer the system of means founded on purposive rationality. Our salvation lies in the system of ends, that is, in the cultural models which orient our behavior.”

Wendell Berry often repeats the same, woefully ignored mantra, the very one I think Pollan believes he propounds: “The answers to the human problems of ecology are to be found in economy. And the answers to the problems of economy are to be found in culture and in character.”

Judaism is one of these surviving ancient cultures, even if many of its members have eschewed its traditionalist outlook in ways both minor and major. Pollan and his peers should know that, similar to many of the other traditional cultures they look to for wisdom, Judaism insists that we express thanks for all foods consumed; eat while sitting; turn meals with other people into more than just individual ingesting (by talking Torah); tithe all agricultural produce, directing a portion of it to the poor (the rest went to the levites when the temple stood in Jerusalem); remove a small portion of any bread dough to be burned up as a kind of home sacrificial offering; reserve special meals or feasts for special occasions, i.e., sabbath and festivals.

Hasidic masters recommended that you stop eating before you are full, just as Pollan learned from other cultures. In recent decades Western Jews have even been generating their own version of the food movement with back-to-the-land farmers, artisanal producers and a new approach to kashrut inspired by environmentalism known as eco-kashrut.

Back to Those Pesky Dietary Laws

But Pollan doesn’t appear to be familiar with the literature on kashrut. In his notes he cites a handful of sources, many of which actually contradict him. Numerous scholars offer sophisticated, creative and cogent interpretations, among them Marvin Harris, Mary Douglas, Jacob Milgrom, Jean Soler and Edward Greenstein. Yet Pollan concludes that, “[the] rules of barbecue […] are as arbitrary as the kashrut [sic], rules for the sake of rules, with no rational purpose except to define one’s community by underscoring its differences from another. We are the people who cook only shoulders over hickory wood and put mustard in our barbecue sauce.”

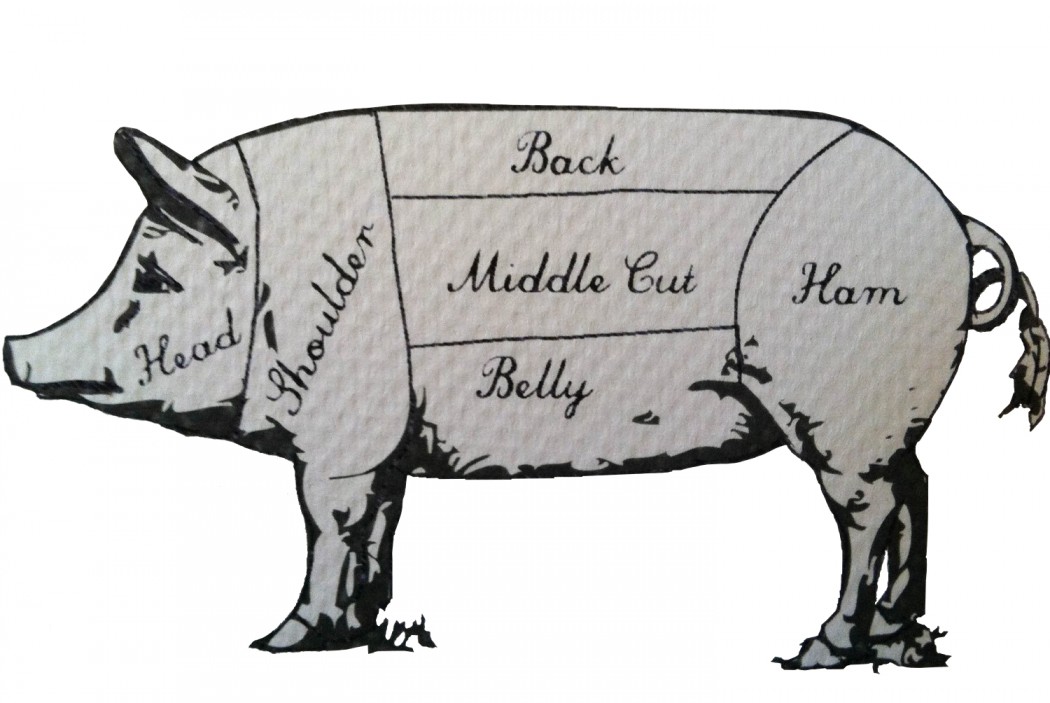

But a more generous reading would see that the pastoral, agricultural Israelites sacralized their natural environment and the limited set of mostly domesticated animals on which they depended. These creatures kashrut declared good to eat. Other animals were deemed to be out of place in the Hebraic cosmos and therefore unsuitable for consumption: most notably, those that fell afoul of inferred characterological norms for each ecological niche—for example, water-dwellers lacking the standard fins or scales of fish, land animals with more than four legs, airborne creatures that were not birds. This taxonomy ended up excluding predators, many wild animals, unusual and exotic beings, and creatures with “extreme” features. The edible Israelite cosmology reflected their idealized self-image: familiar, docile, well-ordered.

Mary Douglas first proposed such a reading of the Torah’s system of permitted and prohibited animals in her seminal work, Purity and Danger, following Durkheim’s insight that a society’s customs, rituals and taxonomies reflect its values. Many scholars took up and honed her theory.

Anthropologist Eugene N. Anderson, Jr., speculated that the animals prohibited by the Torah all consume either blood or excrement, both seen as morally reprehensible. Talmudic statements (BT Berakhot 15a and 25a) support this view when it comes to the pig, as do medieval commentators. Another common explanation of the ban on pig is that it was consumed and worshipped by those the Israelites/Judeans despised (though scholars such as Milgrom dispute this).

It’s easy, of course, to disparage much of the above as imposed identity boundary-creation and -maintenance, but it should be kept in mind that those erecting such boundaries considered, with some justification, Egypt to be a cruel and barbaric empire of hypocritical elites and abhorrent licentiousness, and Canaanite society thoroughly immoral from its forms of sexuality to child-sacrificing religiosity. We don’t have to share these perspectives, or the prohibitions derived from them, but as motivations for a culture they are hardly arbitrary or unique.

Pollan ignores what is perhaps the most common explanation for the prohibition of certain animals, one aimed not at distancing Israelites from others but rather at maintaining the relationship between the individual self and the divine. Rabbis of all eras insist that self-restraint is one of the most vital lessons of the laws of kashrut (of most of the commandments, in fact), regardless of the seemingly arbitrary forbidden entity in question.

Pollan no doubt does not want to offend too greatly by stating outright his repulsion by laws insisting on Jewish separateness from other peoples, though he obviously believes this and he would hardly be alone in so believing. But he also clearly has no use for a culture that places certain food sources off-limits for reasons that are not ecological, biological or chemical, but “only” for moral-pedagogical or spiritual purposes. He reaches the illogical and methodologically strange conclusion that because experts do not agree on a single reason for the prohibition of certain animals no such reason exists. Sophisticated scholars have long abandoned the idea that such a complex cultural phenomenon should have a unitary raison d’être.

Influenced by some of the above interpretations, progressive Jewish thinkers from all major denominations have seen kashrut as a worthy basis for ethical eating. Perhaps surprisingly, many of the authors of essays in the Reform movement’s 2011 anthology, The Sacred Table, while often sharing a distaste for the specific laws of kashrut, understand and acknowledge that their dense and interlaced cultural and spiritual significance should lead Reform Jews to rethink knee-jerk rejection.

All of the aforementioned sources on kashrut were available to Pollan, who is, in most areas, an assiduous researcher. My point is not to prove the superiority of kashrut (much less Judaism), but to suggest that, first, Pollan ought to provide substantive arguments for ignoring it and, second, that kashrut is hardly the only complex traditional dietary system—including Muslim ḥalal, and Hindu and Buddhist vegetarianism, to name some of the more obvious—ignored by Pollan and other Jewish foodies. Kashrut comes within a dense, rich, long-standing culture promoting, ideally, upright, prudent, modest living, including, reverence for and balanced coexistence with the natural world.

The final, and perhaps greatest irony to the dismissal of kashrut, is that Jews through the ages have adopted the local cuisines and food cultures of all of their homelands—whether Persia, Greece, Morocco, Poland, or India—and adapted them all quite adequately to function within the framework of kashrut. One wonders whether Pollan et al think the eco-culinary wisdom of these “traditional” cuisines is diminished when done within the parameters of kashrut?

When Eco-Kosher Pigs Fly: Omnivory as a Universal Ideal

One of the reasons we needed to contrive or rediscover a food culture in the first place is that most Westerners don’t take culture itself seriously. Some in the food movement continue to suffer from this same myopia, a common American antagonism toward history, tradition, family and anything that curtails our seemingly sacred autonomy. A utopian yearning for self-making, for psychic borderlessness, for absolute freedom leads Pollan, Barber et al to believe that in some respect food choices should only be personal, made in a socio-cultural vacuum. Hence the general inclination in the food movement toward omnivory, which would seem to parallel universalism.

But omnivory is a cultural choice, in this case Christian. Which is to say that although Pollan (or, indeed, the culture itself) may not recognize the dominant culture as a culture with its own particularist stances, this omnivory and universalism nevertheless do come from a Western culture shaped largely by Christianity and the secular-Christian movement of the Enlightenment, among other things. As Alan Henkin insightfully noted:

When it comes to eating, we are choosing within competing rule systems about food. […] The proper question is: Which community’s rules about eating do you wish to accept?

We grapple with this question when we consider whose foodways the food movement holds out to us.

Pollan provocatively suggests that pig’s unkosher status should be reconsidered. As far as I can tell he hasn’t fleshed out this recommendation but it’s not hard to tease out implicit arguments in favor: pigs eat just about anything, convert plant energy to animal comestibility with great efficiency, breed easily and rapidly, and require relatively little management. Raised the right way, they offer enormous benefits to small-scale farms as biological systems.

On one level, then, Pollan constructs human omnivory as an ideal; being willing to eat pig or any species, if ethically raised and killed, becomes the ethical path. Within the food movement a confusion thus reigns between theoretical omnivory and avoidance of specific foods based on concerns like personal health, seasonality, the environmental dangers of production, scarcity, etc.

Unfortunately, little sustained research has been done about the contexts, meanings and cost/benefits of omnivory in cultures past and present. Most investigations focus on the perhaps more easily-graspable and less-settled matter of individual dietary choices.

One thing that seems clear is that we participate in an endless dance between the universal and the particular, neither of which can exist without the other. Lines are always being drawn. Will we avoid factory-farmed meat? Pig? An overlap of the two? Neither? Whose mores should be followed and why? It remains unclear whether the food movement’s unwritten rules offer benefits and solutions better suited to contemporary agriculture-industry-health crises than ancient food norms. Only time will tell.

Obviously, many people over the centuries have sought to escape the constrictions of traditional life, of religion, which have their own problems, excesses and blind spots. The goal for the food movement must be how to make use of the best of rationalism and the best of traditional ways. Believing that tradition will “save us” is as deluded as believing that its elimination will.

Jewish tradition itself acknowledges anxieties over law and restricted behavior. One explanation is often cited to suggest that after the coming of the messiah the pig will change its nature—it will start to chew its cud—and become kosher. In a perfected world commandments, prohibitions and rituals may well not be needed, but for the rabbis, reality-based as they were, this utopia is endlessly, if disappointingly deferred. It could also be that this midrash slyly critiques what the builders of Christianity, after the coming of their messiah, had already decreed regarding pigs.

My point, again, is not to berate anyone for not being Jewish enough or in the “proper” way. I don’t give a fig if Jews choose not to keep kosher. But given that a leading intellectual of the food movement like Pollan has been named by Time as one of the world’s 100 most influential people, his views disseminate widely. During the Leonard Lopate interview mentioned earlier, he indicated that he recently gave “a little sermon on kosher” [sic] at New York’s Reform Central Synagogue in which he repeated his comparison of the many rules of barbecuing with those in Leviticus (still not knowing whether goat was kosher when later interviewed by Lopate).

Oy.

Those who otherwise stand for such commendable ideals and values should show more self-awareness and be more familiar with their own backgrounds, sure, but they should also be better informed about the contexts and consequences of their positions. Fabre-Vassas’s eye-opening and often stomach-turning book should be assigned reading for all pig meat lovers, whatever their religion. One might be able to eat it ethically, but that doesn’t make it kosher, and I have yet to hear a convincing argument about why it should be. Pollan and others sounds like they’re suggesting that members of religious cultures who choose not to eat pig sin against the omnivorous wisdom of the new food movement, a curiously intolerant position.