What inspired you to write Places of Redemption: Theology for a Worldly Church? What sparked your interest?

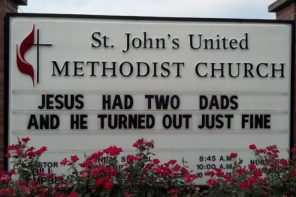

I was inspired to write the book because my original interest in liberation-type theologies, particularly feminist theology, led me to the inevitable judgment that theology should attend to what’s generally called “popular religion.” Theology (my field) needs to pay attention to the creative things ordinary believers do with their faith. So I looked for a community engaged in something liberatory and took a course in ethnography so I could do participant observation in that community. I chose an interracial church, because significantly interracial churches are quite rare in the Untied States. In addition to being interracial, this small United Methodist church included people with disabilities from group homes, and that, too, is rare.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

The take-home message is that churches still have a lot of work to do to move beyond our fears of the racial and “disabled” other; and here I speak primarily for the dominant populations on both counts. To get at the disconnect between the dominant claim of Americans that they are for racial inclusion and their actual behavior, I identify a category of human response called “bodily proprieties,” which draws upon the work of sociologist Paul Connerton. Connerton argues that a society’s identity is not just defined by its written or “inscribed” traditions but by bodily “practices” or habituations, as well, which can help get at the affective and visceral response we have to those who have been socially typified as “other.” To get at the disconnect between “belief” and affective/visceral habituation, the book focuses on unconscious responses which can be identified as bodily communications. On Connerton’s terms, churches’ normative memories, like biblical traditions, do not tell the whole story. The “traditions” of bodily rituals, and techniques (like “talking” with your hands), but also, and most importantly for my book, bodily “proprieties” also define us. Bodily proprieties refer to the enculturated values or habituations that have to do with what is “proper” for particular kinds of bodies, particularly relevant for status markers such as class, gender, and racialization. I look at the racialized bodily proprieties “whiteness” in the church community I studied and assess how they intersect problematically with the habituations caused by marginalizing factors such as “race” and disability. This helps me show the gap in the United States between talk and action. Figures show that, as Andrew Hacker said, what actually has changed are the public claims about welcome and racial justice, not living patterns. This is true of churches as well, as only 2.5% of mainline churches have no more than 80% of membership identified as the same race.

Anything you had to leave out?

I am afraid I left out some of the more complex nuances of gendered bodily proprieties and the way African American women and white women are habituated into different ways of behaving. I also was less successful at portraying the different “racializations” of members from African countries and African Americans.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

First, it is a general assumption by many in the white community that we have moved “beyond” race. The recent anger at Barack Obama’s minister, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, suggests a real obliviousness by many whites about the deeply entrenched and continuing effects of racism in this country and about their own “whiteness.” I found that many of the whites in this interracial church spoke easily of their “color-blindness” and often thought the church had moved beyond racial issues, when, in fact, African Americans did not think the church had dealt with these issues. Secondly, there is a widespread sense that racism and “able-ism” are malicious acts or attitudes. However, by posing these as deeply embedded enculturations, I show how even very well-meaning dominant groups are continually reproducing aversive habits and are oblivious to their own power and dominance. On the good news—there were some profound and moving alterations in peoples’ understandings of one another. It was fascinating to hear Africans talk about their misconceptions of African Americans, stereotypes they had “swallowed,” and to hear African Americans talk of the stereotypes they had of Africans. I was often moved by how the model of Jesus served for many as the warrant to repent of their biases and to learn from the “other.” However, to really learn from the other, to have changes in attitude, had largely to do with slowly altered habituations, which involved working together in situations and with postures of equality. Fears and aversions need changing through lived habituations, not just beliefs about equality.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

My primary audience was theologians, because I challenge the notion that what is most significant theologically “belief.” Because the book makes a case for the affective and visceral character of human responses, particularly responses of dominant populations with regard to those we perceive as “different,” such as people of other races or people perceived to be disabled, it is most fundamentally a call to broaden out the definition of “faith.” The book’s attention to the way people without language—those with a variety of disabilities— communicate, also challenges theology to develop much more sophisticated accounts of human response and, therefore, faith.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Give them pleasure? Piss them off?

Hopefully provoke them to wonder about their own bodily proprieties around folks who are “different.”

What alternate title would you give the book?

Maybe Redeeming Obliviousness: Racism and Able-ism as Bodily Traditions or something more revealing to the actual subject of the book.

How do you feel about the cover?

It’s not bad.

What’s your next project?

I’d like to explore the gendered character of how Christians deal with conflict. I’m more and more interested in the communications which occur in excess of what people say and explicit religious language as well.

Visit our RDBook page for a complete list of our interviews with authors…