Is it possible to coerce someone to pray? Is it still coercion if you say please?

If you ask Peter Bormuth, who is trying to sue the County of Jackson, Michigan for coercing religious participation at its town board meetings, the answer to both is yes.

It’s part of Bormuth’s plea to get the Sixth Circuit to reinstate his case against the county, whose commissioners, he says, open each meeting with a Christian prayer all attendees must participate in, regardless of their beliefs. Since the commissioners are in a position of power, their request isn’t exactly optional, according to Bormuth.

It’s a familiar argument in the realm of sexual consent, particularly in power-unequal relationships like the ones between teachers and students. Of course it’s possible for students to enter such relationships consensually, but it’s also possible for them to say yes to things like sex or dinner for fear of reprisal in the classroom.

At oral arguments last month, Bormuth quoted specific language the commissioners have used before the prayers: “Please rise, all rise, would you please rise, … it goes on. All rise and assume a reverent position. Please bow your head. Bow your heads with me please. Please bow your heads.”

“Does the word please mean that it’s at the discretion of the audience, whether or not to do it?” Judge Richard Allen Griffin interrupted to ask.

“I am the only person who does not rise,” Bormuth said, adding that the commissioners’ requests to “please be silent” and “please rise” are both commands. And when he once asked the commission to change the prayer practice, one of the commissioners publicly called him a “nitwit,” Bormuth argued.

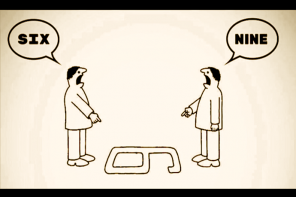

So was Bormuth, in effect, being coerced to pray? The question gets to the heart of the meaning of “coercion” in the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Town of Greece v. Galloway, which said the upstate New York town’s practice of praying before meetings could continue because the local governing body wasn’t coercing anyone to participate. In a plurality opinion, Supreme Court Justice Kennedy said you can’t coerce someone to pray “merely by exposing” them to prayer. There has to be something more.

But in Greece, board members didn’t solicit prayer-related gestures, members of the public were allowed to come and go as they pleased, and the prayers were given by guests, not town officials themselves.

So at what point should courts draw the line between citizens being annoyed by a government official’s religious practice and feeling oppressed, or coerced by it? There’s a whole spectrum of scenarios in which we’re technically free to do things (like not pray, or not accept an invitation to dinner) but still bound by social norms, cultural expectations and power structures (like a town commissioner who might vote down your proposal because you didn’t pray, or a teacher who might grade your paper more harshly after being turned down—even if those reactions are subconscious).

This is part of the reason laws regulating the establishment and exercise of religion are so sticky. Some religious activities, like wearing a prayer shawl or attending mass, can be easily identified as such. But prayer is harder to pin down, especially when other power dynamics are involved.

If I’m at a funeral and people around me start praying, I may notice that I’m the only one not praying, but I won’t necessarily feel coerced to join in. But if a judge who’s about to decide whether or not I go to prison, or a county commissioner who will decide if my proposal is granted, asks me to rise, bow my head, and “assume a reverent position,” I’ll probably go along with it.