Even as Trump threatens to withdraw federal aid from storm-devastated Puerto Rico, ranting on twitter as he witlessly embraces the villain’s role in this ongoing tragedy, heroes have emerged—even saints.

David Begnaud, the CBS reporter who, for his ceaseless and reliable reporting from post-storm Puerto Rico has become such a saint, especially to those Boricuas desperate for any news of their island.

Since the storm made landfall, Saint David of Begnaud has brought news. He was at the San Juan airport, reporting on the humanitarian crisis there, the frustration and thirst; he was in Ponce, interviewing a local police officer about the lack of FEMA distribution in that municipality. David Begnaud, chronicling the desperation and the fear, the inimitable spirit and dedication to community. David Begnaud, amplifying the cries for help, the cries of thirst, praising those delivering aid and, at times (as at the airport), seemingly singlehandedly prompting the delivery of such aid, through his broadcasts.

Since the storm hit, he has been both relentless and reliable, a paragon of old-fashioned, shoe-leather reporting, investigating and clarifying, handing his microphone to the people on the flooded streets.

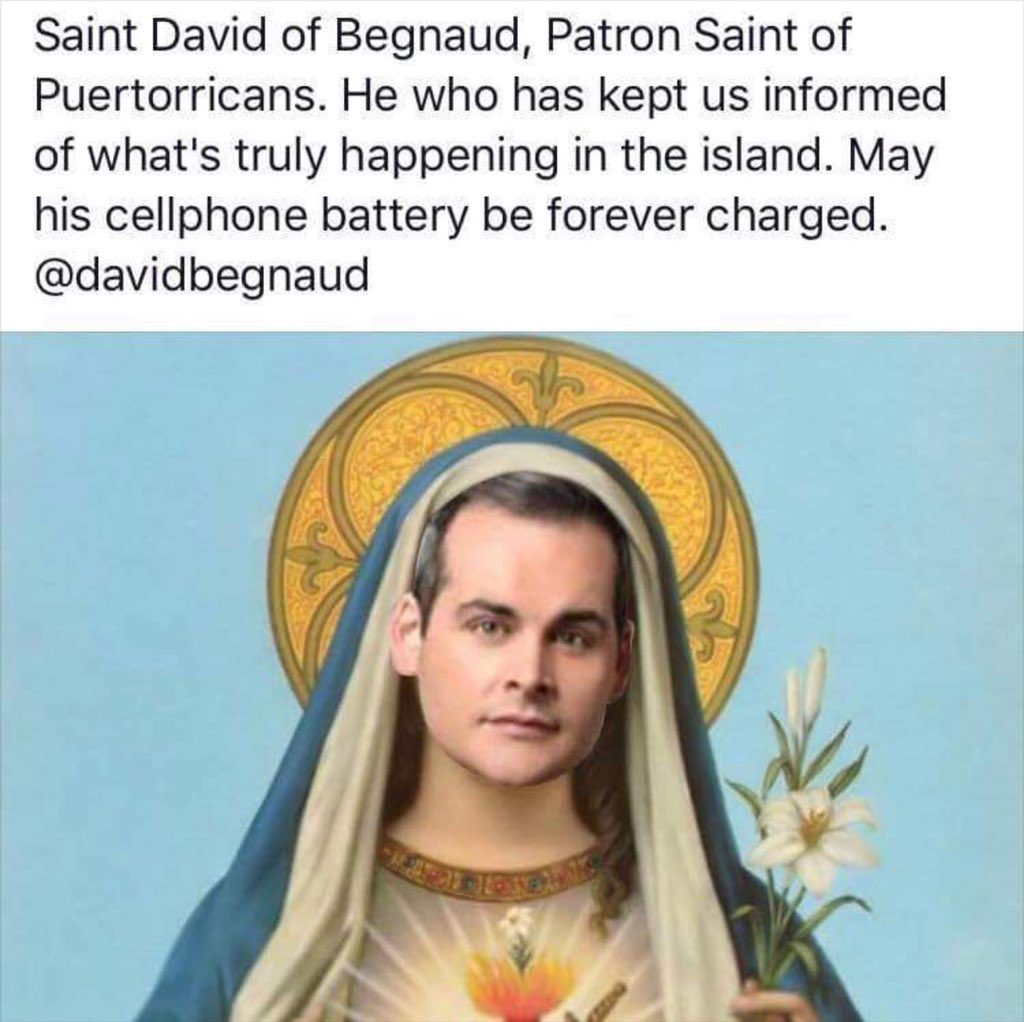

As one Twitter user, among the first to have photoshopped Begnaud’s countenance onto a haloed, prayer card image wrote:

Represented veiled like the Virgin, revealing a pierced and fiery heart radiating from his chest, stickers of this new folk saint are available, to be affixed to prayer candles or otherwise used in devotion. Like so much of our contemporary American moment, it’s a joke, except it’s not. There is a deeply serious sentiment in the popular reaction to—admiration for and awe at—the work Begnaud has been doing. An online petition urging recognition for this work cites “his arduous work, empathy, kindness and overall dedication to giving the world a true glimpse into this catastrophic event that is upon the people of the Island of Puerto Rico.”

One Puerto Rican on the mainland articulates a widespread sense: “You are our source for truthful information.”

Begnaud stands in the face of a storm of hot air and fake news masking inaction, political calculation, and active unconcern. On September 20, Hurricane Maria tore into Puerto Rico. Six days later, President Trump held a Situation Room meeting to discuss the disaster. On October 3, during a brief visit to Puerto Rico, Trump declared the hurricane and its aftermath did not represent “a real catastrophe” and congratulated the Puerto Rican people on how few of them had died—ignoring or denying or simply not understanding that the number of dead was already underreported and already growing. He joked about the effect of this disaster on the budget before posing for a photo op in which he tossed paper towels into a crowd, action he defended in an interview on Trinity Broadcasting Network, a Christian network, reminiscing about the softness and beauty of those paper towels.

The catastrophe, after all, is fake, so the story must be about adoring crowds, amazing towels—must be about Trump.

When the major of San Juan, Carmen Yulín Cruz, warned that her people were being killed by “inefficiency,” and urged the government to “make sure somebody is in charge that is up to the task of saving lives,” Trump reframed the call for help as a personal attack. From one of his golf resorts, the President of the United States derided Yulín Cruz as an “ingrate,” blaming her “nasty” comments (about him) on the Democrats—ignoring or denying or simply not understanding that the comments weren’t about him, but about the people of Puerto Rico, American citizens, many of them suddenly homeless, many more without drinking water or food or electricity.

Trump—not known for maintaining focus—veered from his attack on Yulín Cruz to a general swipe at the Puerto Rican people, using language evocative of a deep history of colonialism, claiming that Puerto Ricans were petulantly demanding that “everything … be done for them.” But such is the strategy behind “alt-facts” and “fake news”: drown out the truth with lies, repeating rumor, and misrepresentation.

Indeed, since Maria’s landfall, Trump has been relentless in his assault on Puerto Rico and the truth about the situation there, from spreading lies about a non-existent strike by truck drivers, to producing a video arguing that the federal response to Maria was a stunning success, to tweeting that “Nobody could have done what I’ve done for Puerto Rico with so little appreciation” as Trump has, or simply reiterating his dismissal of any negative story about the humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico (which now includes a mass exodus of Puerto Ricans to the mainland) as “so many Fake News stories today….The Fake News Media is out of control!”

Faith in Begnaud’s broadcasts—whether fact-checking that, indeed, there was no truck driver strike or documenting how locals in Guayanillas are working to reconnect old pipes to supply water to their communities or providing an update on the bacterial infection Leptospirosis as the probable cause of several recent deaths—is faith in media that is in control, media that is careful, compassionate, committed to a worldview where “news” is something other than entertainment, something more than a task done for a paycheck.

That Begnaud insists he is doing nothing heroic is, indeed, part of his saintliness, key to what he represents in the eyes of those who look upon his work with such respect, even reverence. It is a reverence for journalism and its essential role in democracy. And like the parodic representation of Begnaud as holy icon, this reverence feels simultaneously antiquated in our current moment and like a force worthy of our most fervent prayers.

If anything is going to save Puerto Rico, it is the crusading work of journalists like Begnaud, raising awareness, informing the populace, influencing policy. If anything is going to save American democracy, it will be that same kind of work, by similar and similarly tireless, brave souls. The dedication manifested by Begnaud is one of service, one of sacrifice. While world leaders frame their experience of a massive natural disaster in terms of fun, Begnaud approaches his work out of a sense of duty. Indeed, it was affixed to a sweet tweet about missing his anniversary than one of the faithful posted a link to the prayer stickers. This is a model not only of real journalism, but also of real humanity.

Meanwhile, the deluge of the fake continues. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook and thus, along with Trump, one of the two most famous faces of the fake news phenomenon and its destructive effects on democracy, seemed to compete with Trump for the most thoughtless publicity stunt involving Puerto Rico. In a livestream demonstration of a new “virtual reality” feature described in the Guardian as “part disaster tourism, part product promotion,” Zuckerberg, in the form of a cartoon avatar, waded through the very real, very flooded, residential streets of Puerto Rico. At one point, his cartoon avatar high-fived the cartoon avatar of another Facebook employee who was “with” him in this “journey.”

“One of the things that’s really magical about virtual reality is you can get the feeling that you’re really in a place,” the Facebook founder said, as if the place were nothing but a 360-degree flat screen view. He has since apologized for the stunt, but that he and his team thought it a good idea in the first place is precisely the sort of moral ignorance San Juan Mayor Yulín Cruz expressed bafflement about in regard to Trump: “When someone is annoyed by someone claiming lack of drinking water, lack of medicine for the sick, and lack of food for the hungry, that person has problems too severe to be explained…”

Think pieces will doubtless proliferate, offering explanations. One theory, of course, is that real journalism has been replaced with various forms of fake journalism. From the soft fake journalism of opinion pieces masquerading as news to the hard fake journalism of weaponized lies like Birtherism or Pizzagate, from the soft fake journalism of narrow-cast, insular social media bubbles replacing the difficult democratic encounter that is shared, nation-wide broadcasts to the hard fake journalism of “news” reduced to a competitive entertainment business, this trend represents both a threat to democracy—which requires a populace informed about facts and united despite ideological differences—and basic morality—which requires awareness of a real world outside one’s own experience, recognition of others living in that world, and empathy for their experiences.

Devotion to Saint David of Begnaud reminds us of the need for and power of such an approach, just as his work reminds us that morality is not some abstract, intellectual notion, but a way of acting in the world.

Meanwhile, the disaster in Puerto Rico continues. Around 92% of the people are without power, enduring a shortage of food and drinking water coupled with ongoing flooding and a related, increasing, risk of a public health crisis. At the same time, Puerto Rico remains impossibly indebted to bond holders, and the draconian colonial restrictions of the Jones Act remain in effect. A solution to this unfolding nightmare will come not from prayer but from policy changes brought about by a population moved to action by the suffering of their fellow citizens. If that is the work of a saint, so be it, but that saint is only as powerful as the faithful who rally behind him.