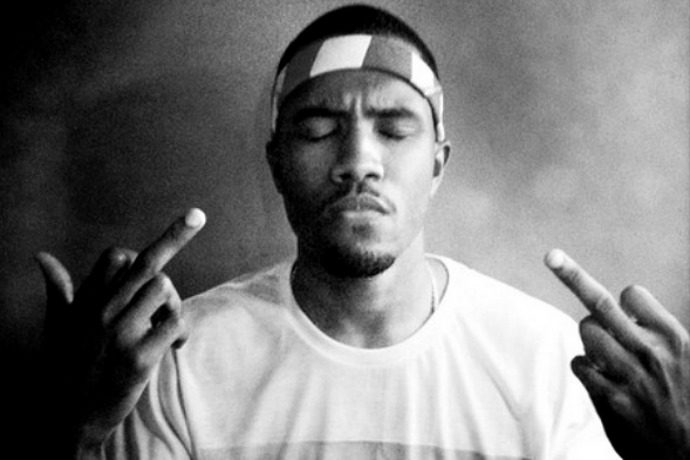

Frank Ocean’s highly anticipated Blonde is only the most recent offering in a remarkable string of theologically complex R&B and rap music. In a year that saw Kendrick Lamar’s Untitled Unmastered, Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book and Beyoncé’s Lemonade, Blonde (initially titled Boys Don’t Cry) only further emphasizes how gospel themes are being increasingly used as a mode of resistance.

Since its release at the end of summer, the album’s message has continued to spread far and wide, making its latest round in the news cycle this week when Kanye West threatened to mount a boycott against the Grammys if Blonde wasn’t nominated.

Ocean has in the past expressed his belief in a redemptive God (“We All Try”) alongside his disbelief in the value of organized religion (“Bad Religion”). In this sophomore work, he further evolves his spiritual identity in the context of racial justice and queer masculinity. The tone is plaintive but also resilient, fitting into an ethos seen from other black artists this year.

I am taking a class this semester with pastor and professor Soong-Chan Rah in which we are currently wrestling with a two-pronged question: first, “What is the Gospel?”—that is, what is the Good News—and second, “How do we communicate the Good News in our immediate contexts?” In times like these, who can say anything about Good News?

As I listen to Blonde, these questions bubble to the surface with every introspective verse, each ambient guitar riff, and the dark, mysterious longings for intimacy (With people? With God? Uhh, with himself?). Searching for Good News in Ocean’s album is a bit like trying to hear and see the good in the world right now—the darkness leaves you deaf and blind.

“It is evident the poor and oppressed are suffering from a famine of justice. It won’t do to wax poetically about heaven, a “renewed earth” or even the resurrection, when God’s Good News of justice seems to have gone missing from our material world. ”

To be frank (pun intended), I have never felt so saturated in darkness, incapable of recognizing even the smallest bit of Good News. A new name becomes a hashtag of protest and mourning all too frequently; Christian orthodoxy and heteronormativity have become synonymous; a maniacal Oompa Loompa is plundering his way to Pennsylvania Avenue. Nonetheless, I remain the stereotypical “Boys Don’t Cry” guy. Instead, I prefer pure, untitled, unmastered rage.

The paradox and profound challenge of Ocean’s album to all of us “tough guys” out here is this: boys do cry. Pushing Ocean’s challenge even further, I want to suggest that the Good News is not only that we can cry or we should cry, but that from the darkness, God cries back.

Ocean wastes no time plunging into the darkness. On “Nikes,” he sings, “RIP Trayvon, that nigga look just like me.” Apart from this verse, a case could be made that Blonde lacks the consciousness present in Ocean’s other work. But I’d argue Ocean sets the mood for his entire album by naming Trayvon on his first track.

Ocean’s lyric “RIP Trayvon” is especially intriguing considering his speculations about the “afterlife.” But his speculations stop short of placing Trayvon in “heaven.” Is there anything more banal than pushing religious platitudes on victims like Trayvon or Aiyana Stanley-Jones or suggesting they’re in a “better place”? The best place for Trayvon and Aiyana was here with their friends and families. But they are not here and so Ocean cries, “RIP.”

The decks are always stacked against the Aiyanas and Trayvons. Ocean puts this reality to words in a heart-wrenching lyric, “you protest and you picket sign, but them courts won’t side with you.” Ocean’s words are pregnant with a hungry negativity. It is evident the poor and oppressed are suffering from a famine of justice. It won’t do to wax poetically about heaven, a “renewed earth” or even the resurrection, when God’s Good News of justice seems to have gone missing from our material world. As theologian Walter Brueggemann insists: God must be “held to justice, and if God cannot subscribe to this earthly passion, then the claims of heaven must be deconstructed.”

Our piety and sanctimonious denial too often prevent us from directing such grown-up talk towards God. But for those who believe God gives a damn, this sort of “real talk” is essential. So with the poetic chutzpah that can only be found in the Hebrew scriptures, Job cries,

There are those who snatch the orphan child from the breast,

[…] From the city the dying groan,

and take as a pledge the infant of the poor.

They go about naked, without clothing;

though hungry, they carry the sheaves;

and the throat of the wounded cries for help;

yet God pays no attention to their prayer.

Considering the name of the track, a Job-like bleakness permeates Ocean’s “Nights” where he cries,

Shooters killing left and right

…

The sun’s going down

Time to start your day bruh

Can’t keep being laid off

Know you need the money if you gon’ survive

The every night shit, every day shit

…

Bummed out and shit, stressed out and shit

That’s everyday shit

Shut the fuck up I don’t want your conversation

Who knows for whom this poetic onslaught is meant? A friend? A lover? Frank himself? Perhaps God? Despite Ocean’s final and caustic verse, maybe he says all this in hopes of creating what Kiese Laymon calls an “echo.” Who will hear the reverberations of his cry? Who will find the words to cry back?

Abraham Joshua Heschel famously claimed that the cries of God are wrapped in a yearning for justice, shrouded in a timeless mystery. This divine cry of protest is always mediated through God’s messengers, the prophets. The prophet Hosea poetically laments, “Bloodshed follows bloodshed.” Ocean, like Hosea, puts his feelings of hopelessness in verse, “That’s the way everyday goes/Every time we have no control.” Barbarity and chaos cause God to cry out,

My heart is turned within me,

My compassion grows like a flame.

God’s burning compassion is on display in the Exodus story as the slaves cry out. It looks nothing like a directed prayer, but their groaning compels God to protest their pain. Even in times where God is tempted to remain quiet in the face of excruciating pain, she is unable to hold back:

For a long time I have held my peace,

I have kept still and restrained myself;

now I will cry out like a woman in labor,

I will gasp and pant.

Christians desperately try to ignore these kinds of passages. In so doing, an even greater chasm has been created between Jewish and Christian theological expression. Christians who connect the Good News with God being in Jesus need to set their gaze upon the embarrassing, naked weakness that haunts his final words,

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

I’m convinced the Good News, in our current context, has no connection to truisms like “God is mighty,” or “God is in control.” J. Kameron Carter knows this is code language that allows religious people—but especially Christians—to remain aloof from the darkness that consumes the marginalized. This aloofness goes directly against God’s hope that her cry of protest will cause others to cry out as well.

The Spirit of God cries with the same moans and groans the black mothers Yolanda Pierce, Kelly Brown Douglas and Beyoncé write about. Long, dark bouts of existential terror make it difficult to see and hear the dignity, strength and beauty of this Good News. As David Congdon says, there will be times where we lose ourselves in the abyss and realize “We may not have a firm grasp on ourselves, much less on God,” but the Good News of God’s love is that, “God has a firm grasp on us.”

God hears the echo of our cry and cries back to us through Frank Ocean’s lyrics,

This love will keep us through blinding of the eyes

Silence in the ears, darkness of the mind

________

For Michael who, like God, cries back.