I’ll admit it: when I saw a link to the viral “Reasons My Son is Crying” Tumblr on Facebook, I had to look. I’m the mother of a two-year-old. Hell hath no fury like a toddler handed the wrong sweater in the morning. How could I not look?

Personally, as I scrolled through the blog, I felt voyeuristic, perplexed, and, honestly, very sad. The sniffles and tears in the photos reminded me too much of my own child. How would I feel if her sadness and pain were encapsulated in tweets and an interview on Good Morning America?

The issues of children’s agency, or lack thereof, in the digital age are ethically fraught, and under plenty of discussion. What troubles yet fascinates me here is our consumption of suffering, even when framed as a joke.

Gazing at pain is not a new thing, as religious studies scholars know all too well. Early Christian martyr narratives drew upon the spectacle of the Roman coliseum and inculcated collective memories. The body of Jesus on the cross calls believers to gaze upon his redemptive pain. Seeing suffering is part of the story of the Buddha as he matures and goes beyond the walls of his palace. It is what fascinates Americans in contemporary culture, from real deaths like Anne Frank’s to fictional suffering children like the ones on Game of Thrones.

What has a crying toddler to do with religion? Obviously, the post is meant to be humorous. But the joke, as Freud argued, performs a fluid and ambivalent role: “we say one ‘makes’ a joke, but we sense that when we do so, we are behaving differently from when we make a judgment or make an objection,” he writes in The Joke and its Relation to the Unconscious. “One senses rather something undefinable, which I would best compare with an absence, a sudden letting-go of intellectual tensions, and then all at once the joke is there, for the most part simultaneously clad in words.” The joke erupts as if it were an ineffable sort of magic, masquerading as a judgment without judging.

For Freud, the joke’s beauty (and its defense mechanism) is in its seeming spontaneity. To explain a joke is to kill it, a point undermined by the flat, unanswerable question of one of the Good Morning America hosts in the interview with this family: “How did you come up with the witty captions?” Like vicarious suffering, we feel the joke. We like or it makes us cringe. We do not usually unpack it. It shuts down analysis with a hearty guffaw. Like a William James-ian notion of religion, it is deeply experiential.

Long before Internet memes and the rise of blogs to the realm of “news,” Freud also understood the irresistible lure of humor: “A new joke has almost the same effect as an event of the widest interest; it is passed on from one to another like the news of the latest victory.” Is “reasons my son is crying” a religious meme, or is a cigar sometimes just a cigar, and a blog just a blog?

While this was not its goal, “reasons my son is crying” trades in religious tropes of seeing, suffering, and empathetic community. Pain is still pain. Believe me, I understand that toddlers can turn their moods on a dime. At one moment, all is tragedy; the next, smiles. As far as we can tell, young toddlers’ sense of time is very much in the moment. Not having the cookie now means not having the cookie FOREVER.

In my book, I argue that stories of suffering children are one way that minority groups write themselves into American stories of sacrificial citizenship. Suffering is seen, suffering is a central part of American history, and horrific moments of agony pierce other people, bringing communities together in powerful yet troubling ways. No wonder a list of even a child’s minor pains—along with the frustrated pain of the parent behind the lens—has caught the eye of so many people.

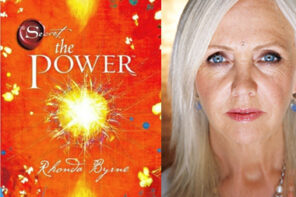

In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor, Greg Pembroke, the father behind the post, explained that he was inspired by the ambitious, gorgeous photography of Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York project which chronicles the denizens of New York City in all of their diverse, vivid, daily glory. In other words, Pembroke wasn’t out to create a maudlin page of woe. He was out to chronicle the quotidian.

In doing so, he inadvertently created community through his chronicle of the anguished, humorous trial-and-error of parenting. This is not just a dancing cat blog. It strikes a deeper chord.

As I scrolled through the blurry images of the Tumblr, I found that picture with the most pathos is a simple one: a shirtless Charlie sitting at a table, staring straight at the camera as tears stream down his face, his eyebrows crooked toward one another like those of another famous, existentially seeking Charlie: Charlie Brown. “I have no idea why my son is crying,” says the caption. That’s the kicker, isn’t it? So often, we have no idea. The infinite gap between one mind and another, even between the minds of those so closely tied to us, is the one we just can’t get over… and the one that so many philosophers, theologians, artists, humans of New York and everywhere, have tried so desperately to overcome.