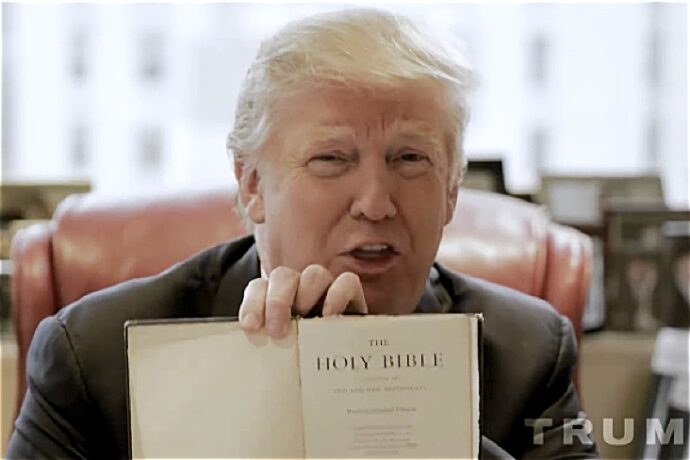

In the Atlantic this morning, Jonathan Merritt writes a bemused narrative of this week’s evangelical about-face as, one by one, the biggest names in conservative Christianity fall in line behind Donald Trump. An “awkward love story,” indeed.

But I want to focus on one thing in particular from the meeting Trump held on Tuesday—it was something Franklin Graham said—to illustrate the way that evangelical beliefs, practices, and emotions function to justify political preferences.

According to a transcript of audio recordings of the closed-door meeting, Graham noted before his invocation that when considering who the next president should be, we often focus on his or her “qualities”—that is, the personal characteristics that make a person fit to lead.

He goes on to say, however, that when it comes to God-chosen leaders, that’s not necessarily the pattern that we see reflected in the Bible.

Some of the individuals are our patriarchs: Abraham — great man of faith. But he lied. Moses led his people out of bondage, but he disobeyed God. David committed adultery and then he committed murder. The Apostles turned their back on the Lord Jesus Christ in his greatest hour of need, they turned their backs and they ran. Peter denied him three times. All of this to say, there is none of us is perfect [sic].

Graham, here, disarms one of the most common charges made against Trump, both from without and from within evangelical circles: that he lacks the temperament, integrity, and virtue to be president.

Graham implies that, although Trump may appear out of step with evangelical values, that’s really no matter, since God uses imperfect people all the time to accomplish His purposes—even adulterers and murderers. This is a point that Ben Carson makes during the meeting as well, when he states that “sometimes God does things in a way that is not very apparent to us. And that’s where faith comes in.”

Nevertheless, Graham simultaneously combines biblical authority, the sovereignty and providence of God, and a statement of human sinfulness to legitimate Trump’s candidacy.

Graham solidifies this claim by going on to consider the matter in more personal terms. Like others before him, Trump may very well be imperfect—but so are we all. Graham goes on:

We’re all guilty of sin. Franklin Graham stands here in front of you today as a sinner. But I’ve been forgiven by God’s grace. He forgave me. I invited Christ to come into my heart and my life. He forgave me. There’s no perfect person — there’s only one, and that’s the Lord Jesus Christ.

Such an understanding of sin and its forgiveness is central to evangelical identity. A recent proposal by the National Association of Evangelicals and LifeWay Research defines “evangelical” as one who accepts four key statements, two of which deal with sin:

-It is very important for me personally to encourage non-Christians to trust Jesus Christ as their Savior.

-Jesus Christ’s death on the cross is the only sacrifice that could remove the penalty of my sin.

While belief is often invoked as a marker of religious identity, we can see that a theological emphasis on sin is central to evangelical self-understanding.

Indeed, this focus on sin is central to the public performance of evangelicalism, especially in politics. George W. Bush, for instance, didn’t shy away from discussing his past misdeeds—which Molly Ivins has characterized as “a life of sin, drinking, womanizing (before marriage) and, by inference, drugs.” He embraced his past as transformed and converted, as a way to emphasize religious bona fides with the GOP’s evangelical base. It’s no wonder, then, that Bush could be described as “a man of faith.”

More recently, former House Speaker Dennis Hastert, who reported to prison this week to serve a 15-month sentence for financial crimes related to the alleged sexual abuse of minors, has apologized for past “transgressions.” Former GOP Representative Tom Delay has described Hastert as a man of “strong faith” and “great integrity.” “I know his heart and I have seen it up close and personal,” Delay wrote to the court in defense of Hastert.

Returning to Graham, although he appeals to a biblical trajectory, he also makes an affective appeal, in the sense that he draws on the feeling or sense of sinfulness that is common to his audience. Sin, in other words, doesn’t rule Trump out but instead humanizes him through shared experience. Hence Jerry Falwell Jr.’s claim, a bit later on in the discussion, “As our friendship has grown, so has my admiration for Mr. Trump. As you know . . . I personally feel strongly that Donald Trump is God’s man to lead our nation at this crucial crossroads in our country’s history.”

As much as we might want to launch a theological counter-offensive against Trump and his evangelical supporters—suggesting that there is hypocrisy here, or some kind of contradiction—it’s not as straightforward at it might seem.

Take a common charge against Trump, that his rhetoric is racist, misogynistic, and xenophobic. I understand the desire to point out how that rhetoric runs afoul of the letter and spirit of the gospel, but it’s also not a line of criticism that works particularly well. And that’s not necessarily because evangelical supporters of Trump are uniquely hypocritical or opportunistic. It’s that a different theological framework is in play, both rationally and emotionally.

Certainly, some Trump supporters share his racist, misogynistic, and xenophobic views. Such views are, unfortunately, part and parcel of many strands of evangelicalism in the United States, and often function seamlessly within a theological framework. Nevertheless, those who don’t share those views, at least overtly, can still justify their promised vote by playing the “sin” card: “No one’s perfect, and God works through imperfect people.”

It’s a sort of divinely sanctioned pragmatism. As Falwell puts it in his remarks, “…while Jesus never told us how to vote, he gave us all the good common sense to choose the best leaders.” It’s important to emphasize that best doesn’t mean perfect, as Abraham, Moses, and David would remind us.

The assumption of God’s providence, however, doesn’t work both ways—that is, it can’t be positively applied to Trump’s presumed opponent, Hillary Clinton. That may seem inconsistent, at least on the surface: if God chooses imperfect people, then can’t God choose Clinton as well, or even instead?

It would make sense to do so, considering that Clinton’s Methodism is well-known and, by her own admission, continues to guide her decisions. Although she isn’t given to frequent and overt expressions of faith in public, she stated on the campaign trial in Iowa this past January:

I am a person of faith. I am a Christian. I am a Methodist. I have been raised Methodist. I feel very grateful for the instructions and support I received starting in my family but through my church, and I think that any of us who are Christian have a constantly, constant, conversation in our own heads about what we are called to do and how we are asked to do it, and I think it is absolutely appropriate for people to have very strong convictions and also, though, to discuss those with other people of faith.

Despite this, Trump could say to his audience in New York, “We don’t know anything about Hillary in terms of religion.”

We actually know a good deal about Clinton’s religious beliefs and practices, of course, but that’s not the level at which Trump pitches matters. When he says “we don’t know anything about Hillary in terms of religion,” what he really means and what his evangelical audience hears is “her faith is not our own.” It’s an appeal to the gut, rather than to a lack of information.

That’s no small matter, since conservative evangelicals commonly divide people in two—there are believers and unbelievers, those who share faith and those who don’t. In the public sphere, moreover, this division is often issue-based. Being on the opposite or “wrong” side of an issue—whether it’s abortion, LGBTQ rights, gun control, all of which put Clinton at odds with conservative evangelicals—isn’t merely an expression of disagreement but, rather, indicative of one’s identity and, ultimately, one’s sin.

That in and of itself doesn’t disqualify Clinton. What does, however, is her embrace of that difference. Sin is ultimately fine for this group of evangelical leaders, so long as one acknowledges it and, subsequently, repents.

What is unacceptable, though, is being unrepentant—and actually embracing what passes as “sin” for evangelicals.

Besides her stance on particular issues, Clinton has said “I would say I am a Democrat because of my Christian values.” For many evangelicals, such a willful embrace of what they consider the very opposite of God’s values puts her on the other side of God’s providence, in the position of evil.

Sure, David was a sinner chosen by God, but he repented; Clinton, according this logic, hasn’t.

All things considered, it may not make rational sense. It can always be turned around, as Clinton herself acknowledges when, after relating her political identity to her Christian values in Iowa, she continues, “but many of my friends would say they are Republicans because of their Christian values.”

But it’s an assumption that’s felt and, in turn, used to mobilize support for Trump against Clinton. As Falwell put it in the meeting:

We have an election between someone who promises he will support issues important to us as Christians, including appointing justices to the Supreme Court who would make us all proud. That’s Donald Trump. And someone who promises she will do just the opposite. That’s Hillary Clinton.

Or, as Ben Carson stated, making a more explicit link with evil:

We need to just keep in mind that Hillary Clinton, when she was in college, was on a first-name basis with Saul Alinsky, who was her hero. Saul Alinsky, who wrote the book Rules for Radicals. If you haven’t read it, please read it. You need to know who you’re dealing with. And on the dedication page, guess who it acknowledges? Lucifer, who gave his own kingdom as a radical.

For the purposes of political mobilization, it doesn’t matter how accurate any of these claims are. What matters, rather, is the way in which theological appeals are combined with certain affects—such as a sense of sin and evil—to justify the Trumpward shift we saw this week.