Day One

If you are someone who thinks it is already too late to keep the climate’s temperature from going significantly above 2 degrees Celsius (about 4 degrees Fahrenheit), COP21 is the place for you to be.

The outside is fascinating, the inside oblique. It reminds me of every United Church of Christ General Synod I have ever attended: all the action is on the border between the inside and the outside.

We will probably save the rich and not the poor, the centers but not the peripheries, the north and not the south. The Pope is a wild card here. Hopefully, he is enough of an outsider to get us inside. He had 3,380,000 hits on his speech to the insiders at the UN. He suggested what’s obvious to the outsiders: let us not commit global suicide.

As Governor Christie likes to argue from his perch in New Jersey, “We’ve always had climate change.” Yup, and we have always had poverty and we have always had disproportionate impacts from what Oxfam calls “Extreme Carbon Emission Inequality.” But we’ve never had climate change that threatened to put the New Jersey Coastline under water for a couple of centuries.

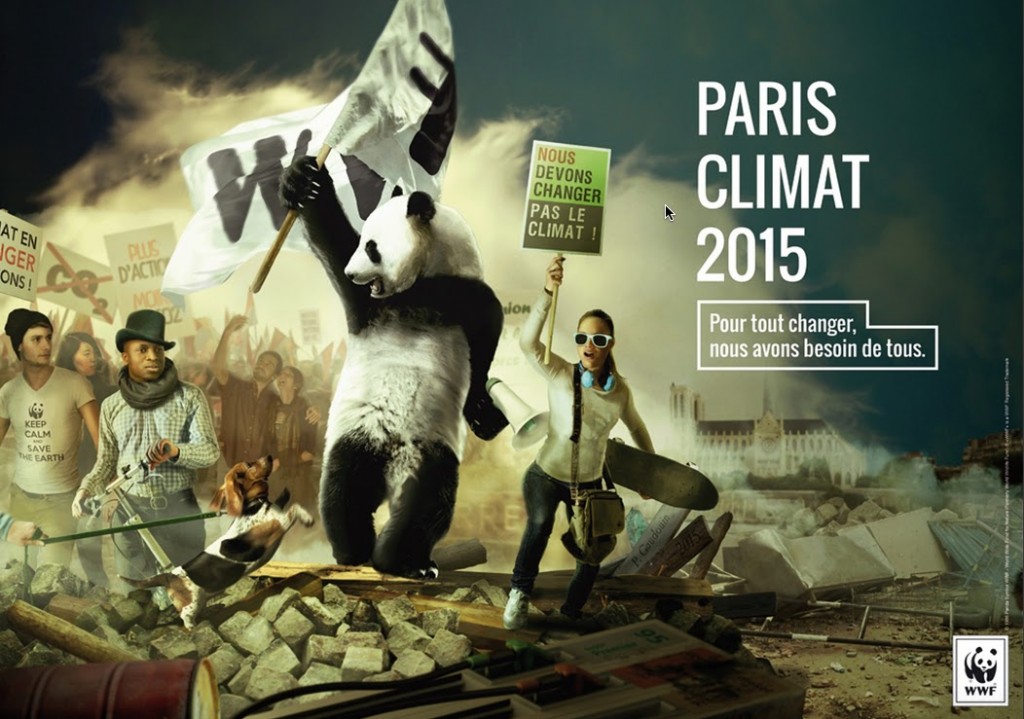

I was so glad that the knock-off from the Delacroix painting of the French Revolution won the World Wildlife Federation poster contest—and is papered all over the RER (the regional train system that takes you out to the conference center). There we see a Panda holding the sign of resistance and hope and a young woman on the verge of skateboarding. The poster has the same fierceness the French showed on Sunday when, after terrorism and the police cancelled the giant kick-off march, they put their shoes in rows on the street. Not allowed to protest, they amused themselves and many others with the amuse-bouche of the human spirit. Ordinary people won’t stop acting and amusing. The question is the spirit of the world leaders who imagine themselves the main course.

Here at COP21 there is a youthful spirit, a nearly Minnesota niceness, a palpable sense of hope. YES WE CAN, SI SE PUEDE is the spirit of every display. Whether the subject is a green bond for large cities or riding a bicycle so that you can charge your cell phone or blend your free smoothie, the spirit has that vibe, that playful spirit of early hope.

Our skateboarder is ready to ride.

Here you can see mushrooms growing out of logs injected with coffee grounds. Beautiful, edible oyster mushrooms. You can buy a nice meal in a glass dish, which is recycled. You can get a free recyclable cup to drink water out of a fountain. You can sign a climate ribbon (which had its first prom at Judson Memorial Church in New York City) and write on the ribbon what you will miss most when the temperatures rise too far to permit the earth’s amusement. You can enjoy headsets, which allow you to understand the Iranian who is talking about how he saved wetlands or the Sudanese woman who went from 28 women in an agricultural cooperative to 5000.

You can learn about resilience in one lecture after another. What is resilience? Here’s what the Equatorial Prize says:

- Diversity of species, culture and institutions.

- Connectivity in Rivers, flyways for birds, open sourcing markets as great as the old silk roads.

- Managing feedback loops. What happens next? Old fertilizer is a negative feedback loop. Compost is a positive one.

- Complex systems thinking, which knows that even the rich are just a part of the picture.

- Nesting governance, decisions made locally and then nested.

- Encouraging ongoing learning.

The resilience of the skateboarders will save us. The world’s leaders may not. Many of them are too invested in what I call the static quo.

I’m not going all the way to hope, as the conference has just started. But I am feeling resilient, which is different from hopeful. It is enjoyment of the periphery, where we are suspicious of any of the insiders who imagine they are the human center, which they are not.

Those inside who know resilience are surely our friends.

Day Two

Day Two for us, Day 5 for the Talks, found us involved with a man high up on a light pole, waving a home made banner of the earth-as-womb, a fetus resting inside.

He was in front of the Grand Palais, an enormous glass roofed building constructed for the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition, where we were trying to see opening day—mistake! You’d think New Yorkers would know this!—of an exhibit called Solutions COP21. His ruggedness and raggedness–the flag had seen more than one demonstration—paled next to the size and elegance of the building.

The young man on the pole was held up by the agility that had propelled him high above the hundred-plus cops staring at him with machine guns in their hands. He was also held up by the energy of 50 or so protesters, meekly shouting their support. The gendarmes were backed up by a dozen police trucks, ready to arrest him and the demonstrators once their hero came down.

Due to the state of emergency in the city, stemming from the terror attacks three weeks ago, all demonstrations have been banned and the police aren’t kidding.

On the other side of the Grand Palais was a long line of people, maybe 200, waiting to get into the major exhibit of the moment: (“Objective: provide a large target audience with an overview of the many products, services, processes and innovations either existing or under development throughout the world to fight climate change and its impact.”). But the line had come to a full stop, even though that was the line for people with reservations. (Reservations? Who knew?)

We had gone for the show, not the protest. Being the kind of people who can neither climb poles or stand in long lines, or wait to get busted by the French riot police (they don’t seem to have read Thoreau on civil disobedience) we went across the street to the Petit Palais, where we enjoyed a wonderfully quirky permanent collection (featuring some amazing Courbet nudes) exhibition and a striking courtyard garden.

From our perch in the Petit Palais, we could watch the bookended scene. Demonstrators to the right, police everywhere in the middle, technology nerds to the left. In the time it took us to enjoy the exhibit, the pent up energy of the waiting crowd and the pent up energy of the protesting crowd diminished, leaving us with a pent up set of questions.

How will the world find a way to express itself if the streets are closed? Where will all the energy here go? And what about all the pent up energy of solar and wind, likewise bottled by interests not its own, interests that even rise up against its use. People talk about “stranded assets,” meaning the coal that will be left in the ground or the gasoline that won’t go into a car’s tank. What to do with them, if we alter the direction of energy use?

Maybe if I had gotten into the exhibit I would know more about these rival energy sources. Or if I had braved the demonstration I would know more about that energy, the kind that lets people un-pent, even re-pent.

The mood today is pent. The so-called more technical talks are over and the political ones are about to begin. Saudi Arabia seems to be everybody’s favorite bad guy at the moment. France, China, the United States seem to be in favor.

And people are looking for a place beyond the lines, outside the reach of the police, to express themselves.

The weekend has been called “A TIME OF GLOBAL REFLECTION ON CLIMATE DISRUPTION.” Time to pray, while waiting. Time to meditate, while waiting. Time to wait.

It is downright Advent over here.

Background on THE PARIS CLIMATE TALKS

The 21st “Conference of the Parties” (COP21) involves delegates from 192 countries who will attempt to work together to fashion a new international agreement on climate change. This will be the 21st COP since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992, acknowledging the existence of anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change a major threat to a sustainable planet.

The Kyoto Protocol, which commits industrialized countries to internationally binding emission reduction targets, was the first climate treaty to emerge from this process. It was passed at COP3 in December 1997 at Kyoto, Japan and came into force in February 2005 when a sufficient number of developed countries signed the agreement; the United States did not, hampering negotiations for the next decade.

A successor agreement, involving all countries and with stronger provisions, is long overdue. A growing number of governments, NGOs and climate activists are committed to making COP21 the occasion for this to happen.