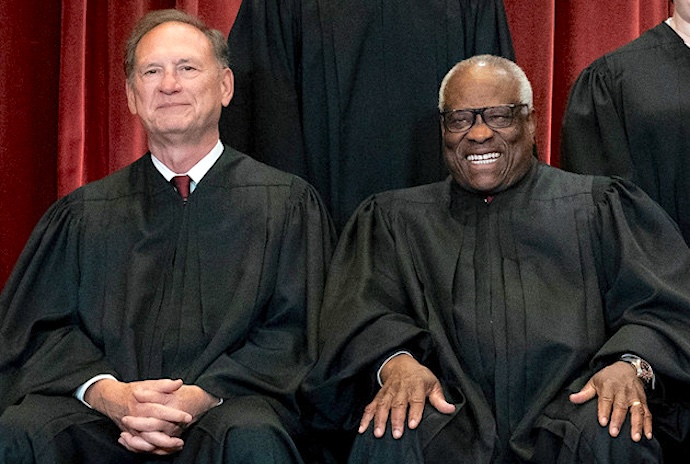

When the Supreme Court decided Griswold v Connecticut in 1965, Clarence Thomas was 16 years old and Samuel Alito was 15. Both men were in their twenties when the court issued Roe v Wade, Doe v Bolton, Eisenstadt v Baird, and Miller v California. Which is to say, Justices Thomas and Alito came of age as the Supreme Court, through decisions on contraception, abortion, and obscenity, liberalized a restrictive sexual order by mooting federal and state “Comstock laws” which, among other things, once prohibited the advertising and mailing of abortifacients.

In March 2024, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments over abortion medication, these two septuagenarian justices signaled their wish to resurrect Comstock laws. A casual observer might come to a myopic conclusion: these anti-abortion justices are invoking Comstock provisions in an effort to once again outlaw abortifacients. But that conclusion misses the bigger picture. By targeting abortion medication through Comstock laws, these justices would resurrect a capacious legal framework that’s anathema to an individual’s right to sexual privacy—to the free flow of information about sex, sexuality, and reproduction, and to the marketing and distribution of devices and medicines used for reproductive healthcare. In short, they would revive laws that made sex and pregnancy more dangerous for women.

Because Comstock laws were never repealed, they’ve remained on the books for decades as dead letter. But the beliefs that underpinned Comstockery never died. If Justices Alito and Thomas’s efforts are successful, a reanimated Comstock law would conflict with decades of jurisprudence that has recognized and expanded a right to sexual privacy, curtailed state prohibitions governing sexual information and sexual representations, and expanded sexual rights and freedoms for most Americans. How that would play out on a Supreme Court with a conservative majority is uncertain. But rights and freedoms that are potentially at stake are concrete and bear directly upon the health of millions of Americans.

At its core, Comstockery maintains that individuals cannot and should not be trusted when it comes to sexual and reproductive matters; they need state supervision, surveillance, constraint, and punishment. Comstock laws were named for their progenitor Anthony Comstock, a 19th century Protestant crusader who was deeply ashamed of his own sexual desires and horrified by the non-reproductive sex acts of others. Comstock believed that the American public had “neither intellect nor judgment to decide what is wisest and best for themselves.” Notably, the purity crusader wrote these words about youth, but he believed them to be true for all citizens. “Evil reading debases, degrades, perverts, and turns away from lofty aims,” he avowed. As Steven K. Green writes here on Religion Dispatches, “He often claimed he was merely performing God’s will in an ongoing war against sin.”

It was in the spirit of purging impurities from the public sphere that he, and the anti-vice organizations he collaborated with, confiscated and burned thousands upon thousands of books and persecuted authors and vendors. These censorious actions were points of pride in the 19th century, so much so that they were emblazoned on the emblem of The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

But Anthony Comstock and his ilk weren’t just targeting the written word; they also targeted information, medicine, and devices that might separate sex from reproduction or interrupt a pregnancy. These laws, over the decades, also suppressed advertisements about contraceptives and abortifacients, and prevented the establishment of birth control clinics in some states.

Sexual representations. Sexual objects. Contraception. Abortifacients. Free speech about contraception and abortion. And the circulation of sexual information or objects through the mails and other “common carriers.” A web of state and federal Comstock laws regulated these and more. And these ensnaring laws caused much misery for ordinary people because they prohibited men and women from engaging in ordinary sexual activities and creative sexual expressions, consuming sexual materials, or deciding how to regulate their own reproductive lives. Put plainly, Comstock laws made sex—and the modest goal of separating sex from reproduction—unnecessarily dangerous.

It’s difficult to encapsulate the scope of the suffering created by Comstock laws. A chronicle of these harms could fill volumes, but two snapshots of pregnancy planning under Comstock will have to suffice. Six decades after their instantiation, Comstock laws still had an informational chokehold on contraceptives and abortifacients. It’s worth remembering that, despite legal restrictions, couples in the 1930s sought to plan parenthood as best they could. In the past, most states allowed pharmacists and doctors to legally prescribe contraceptives to married couples. In the 29 states that permitted them in the mid-1930s, birth control clinics might also provide information and tools to married women to control fertility. Such clinics often required referrals from doctors, hospitals or social agencies. But many—especially the poor and the unmarried—weren’t lucky or privileged enough to access these resources.

Notably, in states like Massachusetts and Connecticut, police and prosecutors would convict and fine reproductive rights advocates who shared birth control information and materials. In 1937, for example, the head of a Brookline, Massachusetts birth control clinic “was convicted and fined $400” for violating Comstock laws prohibiting “exhibiting and offering for sale drugs, medicines and instruments intended to prevent contraception.”

And contraceptive policing extended far beyond birth control clinics. Police fined and jailed entrepreneurs who weren’t authorized to sell birth control. Authorities also conducted raids on establishments selling “illegal” contraceptives, including cafes, gas stations, pool halls and taverns. Newspaper reports indicated that in some cases, the buyers were high school age. But the market for birth control extended far beyond the young and the unmarried.

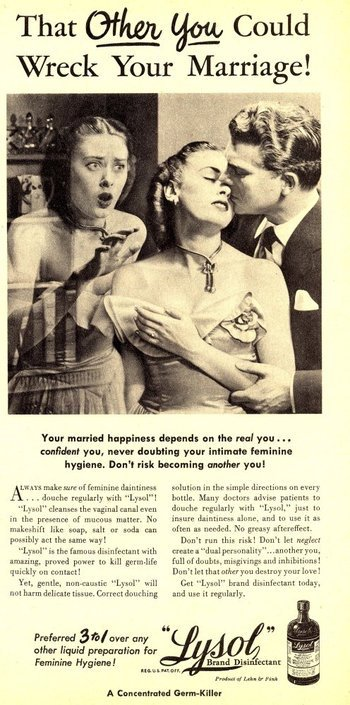

In the absence of access to reliable reproductive healthcare resources, women availed themselves of dangerous and ineffective contraceptive advice and devices. Among these was Lysol. Advertised with a wink and nudge as a “marital hygiene” product, Lysol skirted Comstock laws with innuendo, praying upon the desperation of women who wanted nothing more than to separate sex from reproduction.

Lysol advertisements used coded language to signify that, when used as a douche, the cleaning agent could prevent or even terminate a pregnancy. As historian Andrea Tone has shown in detail, Lysol was just one of a number of unregulated contraceptive products advertised in women’s magazines and in newspapers. Comstockery, in other words, endangered women by creating an environment where quackery and scammers could thrive.

Unsurprisingly, a harsh cleaning product had adverse effects. A 1936 book by Rachel Lynn Palmer and Sarah K. Greenberg, M.D. called Facts and Frauds in Feminine Hygiene, outlined how Comstockery made women susceptible to predation by charlatans. They shared the story of “Mrs. Robert Smith,” a composite of the many documented cases of women injured by Lysol and similar products.

Married “for two months, and living in a small Colorado town,” Mrs. Smith, “was turning the pages of the Ladies Home Journal” when she found an advertisement insinuating that Lysol could help prevent pregnancy. She wanted to defer having children until the couple was on firmer economic footing. “Their old family doctor had been of no help, and Mrs. Robert Smith had never heard of a birth control clinic,” the authors recount, “so she clipped the coupon at the bottom of the page and sent for the booklet containing “Facts about Feminine Hygiene and other uses of Lysol.”

The Lysol booklet instructed readers that “the effectiveness of your practice of feminine hygiene depends on the preparation you employ in your douche,” and that “Lysol is ideal for this purpose.” Certain that Ladies Home Journal would never advertise a dangerous product, she bought a bottle of Lysol and prepared a douche of the caustic material.

Facts and Frauds in Feminine Hygiene made clear what medical journals and newspapers had documented: by using Lysol as a douche, Mrs. Smith was at risk of severe burns, inflammation to genital tissues, and even death. And Mrs. Smith represented the plight of countless women endangered by a lack of medical resources and information.

The stigma around sex and contraception has hidden the pain caused to their private parts and lives from public view. We therefore have to read between the lines of the many newspaper articles about injuries caused by Lysol and similar products. In 1934, for example, a short news item in the Hammond Indiana Times reported how two unmarried eighteen-year-old “Chicago girls are in St. Margaret’s hospital today, severely burned about their legs from lysol disinfectant.”

The two women “received their burns in a washroom in Johnny Nichols’ beer tavern,” the article noted, after arriving there in the company of their boyfriends. The vagueness of the report and the context clues it offers, suggests that the young women who badly injured themselves were douching after being intimate with their lovers.

The two women “received their burns in a washroom in Johnny Nichols’ beer tavern,” the article noted, after arriving there in the company of their boyfriends. The vagueness of the report and the context clues it offers, suggests that the young women who badly injured themselves were douching after being intimate with their lovers.

Even three decades later, in the 1960s, the use of unreliable remedies—from Lysol to Coca-Cola douches—was not uncommon. Meanwhile, women in states like Connecticut, one of the last holdouts when it came to Comstockian contraceptive laws, would travel across state lines to get access to birth control. Poorer women or those without informational resources found themselves with unwanted pregnancies. Some carried to term pregnancies they neither wanted nor could afford. Others sought to terminate such pregnancies, a highly risky proposition in a pre-Roe world.

With Griswold v Connecticut in 1965, the Supreme Court recognized that married couples had a right to sexual privacy when planning parenthood with physicians. Which is to say, Griswold dealt Comstock laws a significant blow. This decision helped set a precedent for other cases such as Eisenstadt, Roe and Doe. But until these cases were decided in 1973, the Comstockian stranglehold on reproductive information, especially when it came to abortion, was pervasive across much of the country.

“I feel the necessity of describing the difficulty one may have in gaining the necessary information needed in seeking an abortion,” an Illinois mother wrote in 1969. This woman, a mother of nine, lived in Monmouth, Illinois, a small town 200 miles west of Chicago, near the Iowa border. When she “discovered that beyond a doubt that [she] was pregnant,” she “was not prepared to cope with this physically or mentally, having nine children already,” so she decided to seek an abortion.

This overtaxed mother relayed how her husband, a prominent chiropractic physician, asked a number of his medical colleagues “where we could get information on abortions and found that they were no more informed than we were.” It took the woman nearly two months to find reliable information. Well into her third month of pregnancy and increasingly distressed, she feared she would be compelled to have a 10th child.

Although this woman, after considerable perseverance and expense, eventually found someone in England to help her terminate her pregnancy, many more were not so lucky. Despite the scarcity of information about abortion and the illegality of the act in most cases, women sought to terminate unwanted pregnancies by the tens-of-thousands. Some sought out illegal providers. Others self-aborted. The danger of both was evident in the existence of septic wards devoted to treating botched abortions.

One of these was at Cook County’s Public hospital on Chicago’s West Side. It was a 40-bed ward, often filled to capacity, devoted to women injured from illegal abortions. One doctor who did his rotation on this ward recalled: “They hurt themselves, perforated their uteruses, they came in bleeding, with difficult-to-treat infections.” Another doctor had similar horrific memories. “I saw chemical burns, as well as perforations of the bladder, vagina, uterus, and rectum. Some women came in with overwhelming infections or in septic shock.”

These are just a fraction of the horrors from the world that Comstock made. In curtailing the information about and access to reproductive health care, misinformation and predacious entrepreneurs thrived. Women, desperate and afraid, availed themselves of unvetted information and resources to help control their fertility. And many did so with tragic results. The archives are filled with the stories of women who were injured or killed by illegal abortions gone wrong.

For those tempted to argue that we’re too sophisticated to turn to something like Lysol (or that the internet holds all the information we could possibly need to access contraceptives and abortifacients), recall that during the Covid pandemic Lysol itself felt the need to issue a warning that its products should not be “administered into the human body (through injection, ingestion or any other route).”

When two Supreme Court justices flirt with Comstock, they’re sending a clear message. In the wake of Dobbs, which jettisoned precedent and overturned Roe, they’re saying, in effect, that it’s open season on the landmark court cases that gave Americans sexual privacy and reproductive choice. How many more will suffer should they succeed?