Andrew Seidel’s piece on RD discusses Rick Santorum’s racially incendiary remarks about Native Americans and the dangers of Christian Nationalism, but I want to take the conversation in a slightly different direction. Speaking at the Young America’s Foundation last week, Santorum stated: “We birthed a nation from nothing. I mean, there was nothing here. I mean, yes we have Native Americans but candidly there isn’t much Native American culture in American culture.” I want to show how relegating the genocide of America’s first peoples to an unfortunate historical side note is foundational to white Christian nationalism.

Santorum’s comments represent a widespread understanding of history within the Religious Right. Religious Right leaders, going back to Jerry Falwell’s “I Love America” rallies from the 1980s, tell the story of a country with divinely inspired origins. This dual justification and dismissal of genocidal history has a theological foundation. Linking the colonial project of European-American expansion in the Americas to the Exodus narrative worked to sanitize the violence of conquest, genocide, and enslavement by framing America as a promised land and a gift from God, thus tranforming racial terror into divine inspiration.

Historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham shows how the Great Awakening and the “city on a hill” discourse that has dominated U.S. public culture made the Exodus narrative the property of whites. As Albert Raboteau and others have argued, African-American Christianity offered a contrasting reading of Exodus, one rooted in experiences of racism and one that can fuel resistance to white supremacy.

The white Christian Exodus narrative continues to dominate the Religious Right. Take for instance a popular DVD Bible study program published by Focus on the Family, called The Truth Project. The Project was created to teach what was described as a “biblical worldview” and over three million people have completed the Bible study program.

One lesson of the Truth Project focuses on the story of American exceptionalism. The presenter discusses a set of paintings in the U.S. Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C. that, he says, all demonstrate the divine origins of the nation. Each painting depicts key moments of the colonization of the Americas—from Columbus to Pocahontas’ conversion to the Pilgrims’s arrival—each painting is described as containing a message that God takes a special interest in the nation. The first painting, “Landing of Columbus,” portrays a conquering Columbus planting a flag on what is likely Hispaniola, claiming it for Spain. In describing this painting, the video narrates a racial origin-story of the Americas. Through framing Columbus as the first bearer of Christianity to the Americas, the narrator portrays the ensuing genocide and colonization as Godly work.

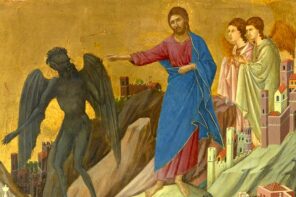

While the historical record is clear that Columbus engaged in extreme acts of violence, the narrator describes Columbus as having “suffered greatly at the hands of historical revisionism.” Instead of serving as an agent of colonization and genocide, he revives a longstanding story that Columbus was working for God. He continues, “Christopher believed that providentially he had been given the name Christ-opher, which means one who bears Christ. His purpose has been re-written. Why?” he asks, without waiting for an answer, but implying it’s the devil’s work.

Instead of focusing on the violence that followed Columbus’ landing, both through the accidental spread of pandemics and centuries of deliberate killing, the Truth Project tells us to focus on Christ, through Columbus. Conversion is central, colonization and suffering not even worth a mention.

The cruelty of Santorum’s words reflects this much broader belief in white Christian nationalism. Celebrating the United States as a divine project requires framing this history of racial inequality, and the genocidal campaigns against First Nations people that went into forging the U.S. nation, as an unfortunate side note, and not the foundation.

This refusal allows for the acceptance, even demand, for other forms of violence. Recently I wrote a comparison of the Left Behind Series—the most popular novel within white evangelicalism—and The Turner Diaries—the most significant novel in white nationalism. The similarities take over a page to explain, as they share everything from narrative structure to a celebratory view of environmental destruction to even using the same phrase when describing an epic battler where the protagonist’s enemies’ dead bodies create “rivers of blood.” Both of the narratives end in genocide, either of non-whites, queers, and race traitors, or of non-Christians. In this regard it’s the Left Behind series that is far more violent. For in Left Behind the Earth is merely a holding cell where battles occur between good and evil so that those who prevail receive the real reward, a heaven elsewhere, and the Earth itself is destroyed.

Despite including gruesome scenes of violence, Tim LaHaye described the bloodshed of his books in this way: “The Rapture is a time of incredible mercy and grace. If you only look at the people who defy God, it’s a negative time. But if you look at the whole population, it’s a blessed time.”

In LaHaye’s “blessed time” I see a continuation of Santorum’s “we birthed a nation from nothing” comment. Both focus their attention on white Christian protagonists following divine inspiration with a few unfortunate—if genocidal—consequences that should remain in the margins. Focus instead, we are told, on God and God’s peoples, for this is glorious.

If we instead step outside of this white Christian narrative and reckon with the suffering this history produced we are faced not with evidence of divine inspiration but with cruelty. From the centuries of outright wars against First Nations people to generations of children stolen from their parents to be brought up in boarding schools attempting to “civilize” native children through stripping them of their culture, contemporary Native peoples are resilient survivors of centuries of genocidal attempts to make them and their cultures extinct. This is a history that should cause shame and calls for reparations and a repairing of past wrongs, not a celebration as in Santorum’s and the broader Christian Right’s telling.

Lakotah writer Richard Twiss has written that much of U.S. evangelicalism is so associated with European-American norms that Native American evangelicals are often treated by white Christians as though they are practicing an impure, or incorrect Christianity. Whiteness is so central to much of evangelicalism that it remains an invisible norm, one that justifies and dismisses violence, both rhetorical and actual.

Santorum and the broader white evangelical community need to ask themselves a question posed by the president of the National Congress of American Indians: “Make your choice. Do you stand with White Supremacists justifying Native American genocide, or do you stand with Native Americans?”